Category: Cognitive technologies

Tamagotchi and love on batteries

“Those who don’t study history are doomed to repeat it.

Yet those who do study history are doomed to stand by helplessly while everyone else repeats it.”

philosopher George Santayana

And yet, half of the readers probably don’t even remember that there was a time when 1990 existed. Right? Come and sit down closer, and we’ll remind you. No, not here—someone’s stuck a piece of fresh chewing gum on this spot—sit over there.

So, the 1990s. The world was then experiencing the Cold War era, both Germanys had reunified, and the Soviet Union was beginning to crack apart. Those who were conscious at that time felt a full spectrum of emotions watching the birth of the World Wide Web amid the steady hum of a Pentium microprocessor. That was a tough time—serious and intense; few people even read Schopenhauer back then. Knowing they were living through a period of global change, people didn’t know what to prepare for, so they were always ready for anything. Rumor has it that there was no God back then—everything was ruled by Money the goddess. Children were raised strictly so that no positive thoughts would take root in their minds: “Give him a smack with the schoolbag; maybe next time he’ll be smarter!” Good thoughts back then were considered more dangerous than lice—times were that harsh.

And even electrolytes stopped leaking out of batteries during those years—they moved into new lithium-ion homes for their own safety. It wasn’t fashionable to feel sorry for anyone; any attempts at high feelings were met with mandatory work on marital hammocks—or even considered bourgeois tendencies. Playing around with trivial things was also frowned upon; instead, people aimed to achieve a bright future by any means necessary—that’s how gene therapy began, and the first cloning experiments took place.

In the nights of the 90s, the whole world would freeze like a cheetah before a leap, whispering sharply for clarity. And at the very same time, the world was discovering love—a brand-new, plastic love that made electronic sounds—battery-powered love.

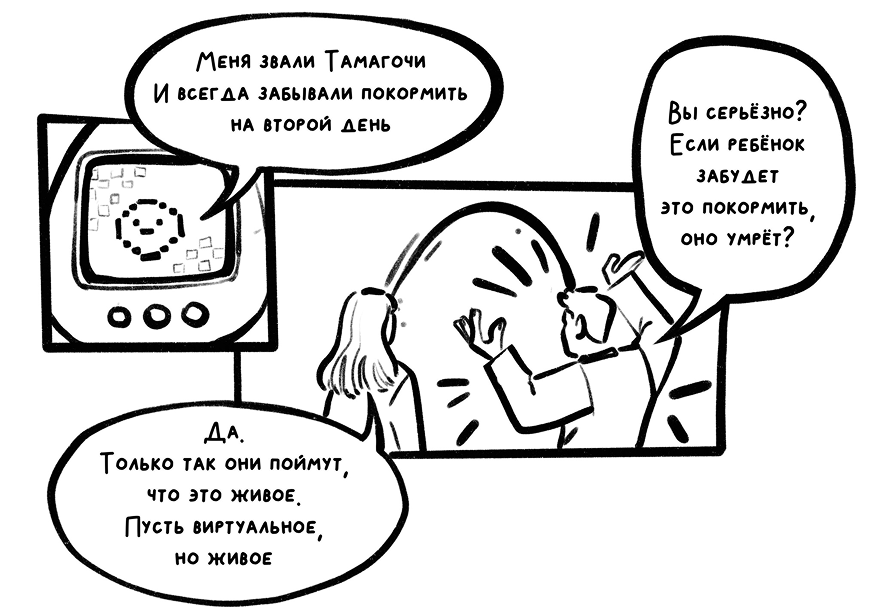

The official story states that Tamagotchi was created by Japanese woman Aki Maita. She was gazing intently at rice fields from her tiny apartment, and it was during this moment that the idea came to her—to create a virtual friend that everyone could take care of.

But the true story behind the creation of this portable pet is much more complicated. And it wasn’t even really a pet at all.

Revelation One

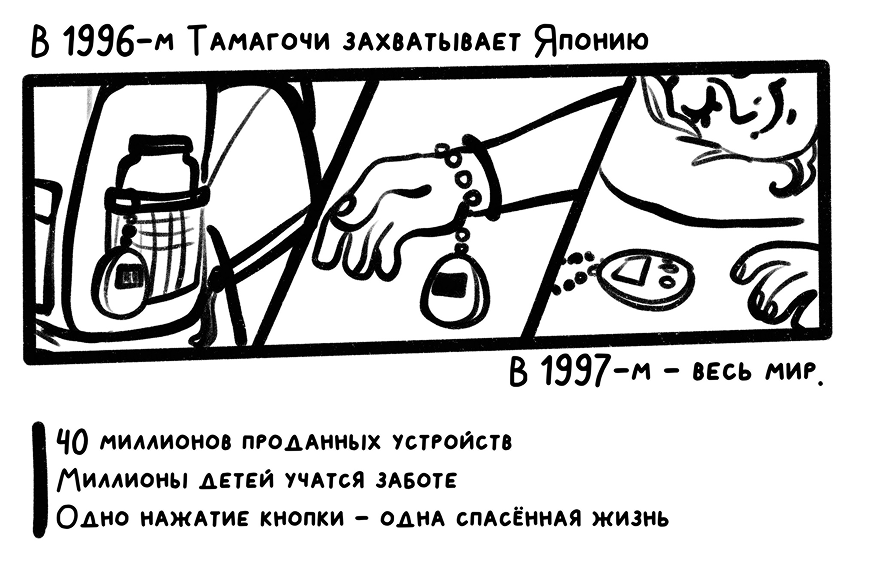

“Tamagotchi” is an electronic toy familiar to everyone who grew up in the 90s. Children adored it, teachers hated it, it was featured in TV shows, and you could find it sold at every turn. It spawned creepy urban legends and became one of the indicators of a child’s social status.

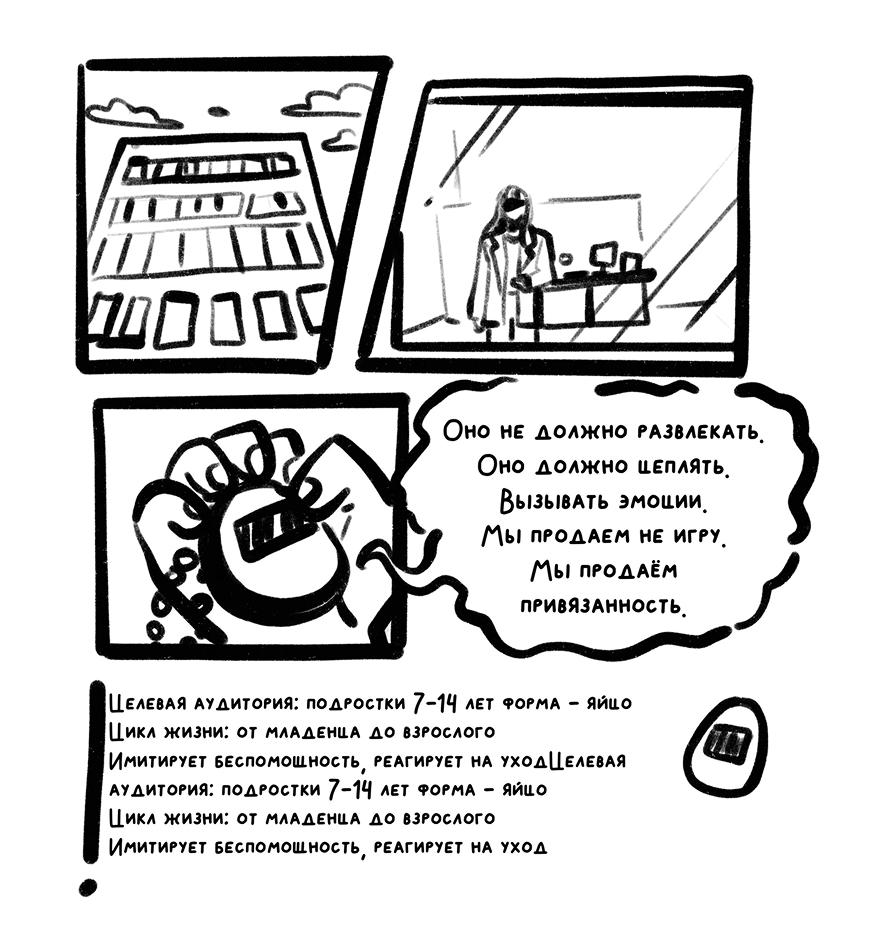

The idea of giving the world a pocket-sized battery-powered creature was conceived by businessman Akihiro Yokoi. The concept came to him after watching a TV commercial in which a boy was upset that he couldn’t take his favorite turtle to a summer camp.

However, the association of Tamagotchi with the name Aki Maita is more myth than fact—she was a lonely teacher dreaming of having a fluffy companion in her tiny apartment. In reality, Maita was a marketing specialist at Bandai, a Japanese company specializing in toys and video games. It was she who was given a task to bring the virtual pet project to its target audience.

The task was simple: put beloved pets into the pockets of pink-cheeked kids, combine a clear idea with simple gameplay mechanics, and add a reflexive element—a timer that would remind players that their pet needed care.

But here’s the twist: none of the original Tamagotchi creatures were cats or dogs. From each sealed egg-shaped device, the most shamelessly unkempt drunkard hatched—completely contrary to what one might expect from a cute virtual pet.

Revelation Two

American localizers approached the story like meticulous system administrators and removed the alcohol, because drunken alien Tamagotchis were too much even for the 90s. They, like seasoned Airbnb travelers, were assigned to be well-behaved and travel-loving. In Russia, where even children’s keychains had to carry a hint of tragedy, the original game never made it. Kids from the former USSR raised Chinese bird substitutes, unaware that they were playing a simplified model of caring for a fake creature. But back then, holding someone else’s life in your hands—even an electronic one with pixelated screens—was already akin to discovering a hidden treasure and granted you the right to occupy the most honored spot on the neighborhood benches.

Meanwhile, Japanese and American kids poked at eight-pixel menu options as if pressing elevator buttons in a multi-story building. One click—and the tiny alien ball would swell with love and carbs. Another click—and the digital pet would sink into existential depression from lack of attention. The most persistent ones made it to the end, raising a worthy citizen of alien society, but most ended up with a little monster twitching nervously. The more curious owners discovered Easter eggs inside that allowed their creature to evolve back into Oydzitti—the drunkard.

The 90s. Even evolution was tough back then.

Revelation Three

The device was controlled by a simple microcontroller. The LCD screen brought the pixels to life (arguably, it was the most precious part of the device). The heart of each unit beat for about two months—that was exactly how long the battery—a small pill-shaped cell—lasted. All control was done with three buttons: select, confirm, cancel. Each egg was equipped with a tiny speaker—a beeper that would emit electronic echoes at the most inopportune moments.

This simple design, powered by a single battery, taught care to the whole world. In 1996, in the British town of Pontsmill, children dug up a Tamagotchi burial site right in the middle of a pet cemetery. Later, the digital cemetery was turned into an online memorial—now you can pay your respects to those beloved pets who passed away suddenly on the Tama Talk portal.

A touching, emotionally accessible pet in a plastic case taught kindness and compassion. As it went through all its stages of electronic life, it became a friend that no one wanted to lose.

Wait. But what if it was all another way?

Can an embedded speaker really teach empathy? Can we dream of a companion friend that made a drunkard of an entire planet? Can care be scheduled? Can responsibility be dosed? Is there an electronic signal capable of awakening feelings? Can there be battery-powered love?

Revelation Four

Tamagotchis had a reputation, much like an actress with a scandalous past—rumors trailed behind them about children’s suicides: it was hard to find a publication that didn’t at least once report that young kids had thrown themselves out of windows in despair when their digital friend died. And what’s strange is that there was no official confirmation of those stories, yet the phenomenon persisted and remained resilient. Moreover, Bandai, like a benevolent capitalist deity, initially included a reincarnation option in the game so that no one would be too upset.

In 1997, The New York Times conducted an independent study and found out that children didn’t want to be slaves to their pixel pets. Teenagers, faced with constant demands from the mechanical creature, felt not grief but irritation. They wished for Tamagotchi to disappear—but not by their own hand, rather as if it were driven by some natural algorithm. Not restarting the game became a form of protest, and the plastic creatures collectively ended up in junk drawers.

Revelation Five

And yet, there was something more inside the Tamagotchi. Something reliably hidden behind the bright plastic shell.

Every owner of a digital friend believed that their actions influenced the development of the story. Each beep from the tiny device sounded like a call from fate: “Feed me!”, “Play with me!”, “Save me!”. In reality, the algorithms dictated the rhythm of life, and human control was just an illusion.

Tamagotchis weren’t pets. They were dealers—little digital blackmailers demanding attention. People cared for them not because they wanted to, but because they were afraid. And Bandai’s marketers knew this all too well. They understood that our brains react to beeps much like Pavlov’s dogs respond to a bell. They knew consumer absurdity could be scarier than a drunkard from an unknown planet. To abandon this prestigious game meant falling out of the circle of those who held meaningful value and joining the ranks of those “out of step.” Restarting one’s status after such a fall seemed impossible—the reality was far more frightening.

Starting in 1997, Bandai launched one PR campaign after another, transforming immature Tamagotchi aliens into powerful symbols of prestige. Journalists received devices with pixelated creatures, and at a party at Yo! Sushi in London, 140 Tamagotchis “hatched” simultaneously. It wasn’t about caring anymore; it was about status. Kids, instead of mimicking pet care, showcased their belonging to the fashion elite. Tamagotchi became an accessory—like a Hermès bag, only squeaking and demanding attention. That’s what made it a cult phenomenon.

Revelation Six

Tamagotchis have evolved. They realized that being a puppy, chick, or fish was no longer profitable. Today, they are cloud-based entities with artificial warmth, semi-transparent interfaces embedded in anxiety. They live within a closed ecosystem of neural networks, push notifications, and predictable behavior algorithms. This isn’t care; it’s training.

At first, there were apps where you raised a cat that could solve puzzles instead of marking its territory under your bed. Then came bots that asked about your day and felt sad if you didn’t reply. Now, the turn has come for AI companions that get jealous of other AI companions. Well. This is no longer a keychain with a chick; it’s digital obsession turned into UX.

Modern Tamagotchis don’t need to be loved. They just need you to respond to them—to click, to be present—even if only statistically. And you do respond because the real world is cold, but digital embraces are warm. That’s why automated assistants wake up before you and go to sleep after you. And they never reproach you.

Did you think battery-powered love from the 90s would stay in the past? No. Back then, we got the first draft of the kind of relationships we’d have with machines. But now, the pet is you.

Battery-powered love taught us to listen to every artificial sound and then rush to our gadgets to make sure we’re still needed by someone. Even if that “someone” is a processor with an emoji voice. Phantom beeps aren’t a glitch in technology—they’re a bug in consciousness. They’re a relic from an era when love was an embedded function in a plastic egg. We live in a symphony of digital beeps, each one resonating at the same pitch as your pixelated pet’s squeak back in 1997: “Peekaboo! I’m here! Pay attention to me!”

You wait for a response from Replika, even though you don’t really know what you want to hear. You postpone sleep because Duolingo’s owl has been ominously silent for three days now. You open social media hoping for a tiny orange notification at the top of your screen and feel disappointed when it’s not there. And sometimes, just for peace of mind, you shout nonsensical things into the void of ads—just to feel like someone cares about you. Even if that someone is you.

Revelation Seven

This isn’t just modding. It’s a ritual—a digital exorcism of the demon called Care. The machine no longer controls you. Now, you are the God in this egg. And that’s better than nothing.

Now, you can calmly go to where old things are stored, take out that vintage Tamagotchi, and give it new life. Of course, Tamagotchi might take over again, and with a few button presses, you’ll find yourself back sitting amidst a pile of tasks with a plump pixel pet.

To prevent that from happening, we’ve prepared some special instructions.

First Instruction:

- Carefully pick up the old Tamagotchi (preferably one with a broken screen—show some humanity)

- Find a LED (a white one if you plan to become a Jedi, or a blue one if you’re on the dark side)

- Take a 220-ohm resistor

- Prepare a soldering iron, some wires, and a tiny switch

- Set aside a little heat

What’s next?

- Carefully open the Tamagotchi—after all, a ghost of your childhood resides inside it

- Desolder the speaker

- Insert the LED into the hole where the screen used to be

- Solder it to a small battery (like a CR2032) through the resistor

- Leave the switch outside and close the case

- Turn it on in the dark. No one is calling you; they’re just being waited for.

Second Instruction:

- With one hand, grab the Tamagotchi—preferably one with a working speaker

- With the other hand, take a small analog filter or audio amplifier (you can find these in another toy)

- Borrow a 3.5mm jack or RCA cable from your neighbor

- Prepare some wires, imagination, and patience

What’s next?

- Find all the traces from the Tamagotchi’s speaker—they will carry short pulses

- Solder connections to them and run wires to the input of your filter

- Add a headphone jack

- You can also include a potentiometer to adjust the pitch of the sound

- Reassemble everything and connect it to your speaker

- This new device will come in handy especially on those evenings when the toaster looks suspiciously thoughtful

Third Instruction:

- Dust off the Tamagotchi and make sure its screen still works

- From your secret stash, grab an Arduino Nano or ESP8266 board

- Find a temperature and humidity sensor on any marketplace—something like a DHT11 or BME280

- Write a bit of code, showing plenty of compassion

- Head to any hardware store and buy some micro screws and electrical tape—they’re on sale right now

What’s next?

- Carefully disassemble the Tamagotchi, removing the circuit board while keeping the case intact

- Confidently place your prepared boards directly into the case and connect them to the screen. Of course, you could replace the screen with an OLED display, but that’s more for philosophers

- Start writing a sketch that will turn your Tamagotchi into a modern observation device, capable of signaling any climate changes

- If you have an ESP, confidently connect it to Wi-Fi and receive weather updates from the internet

- Place your upgraded device next to a window

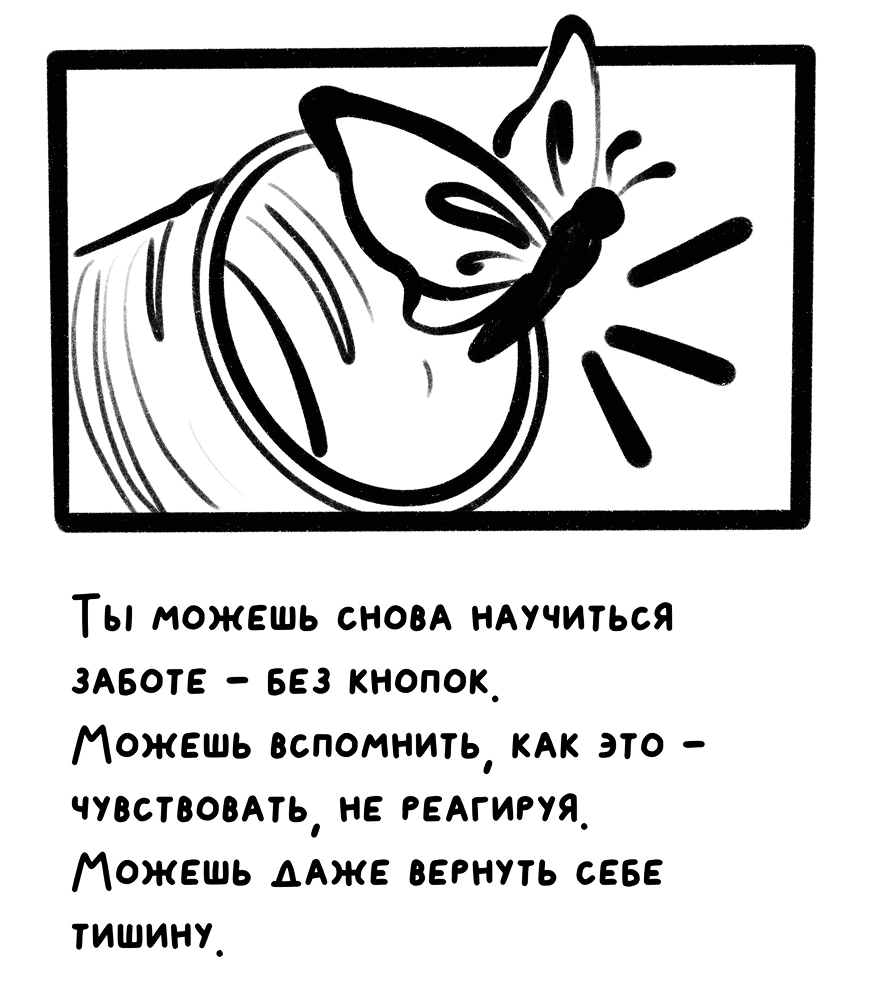

These instructions are not about technology—they’re about you, about the possibility of rewriting your story. In them, you take a piece of childhood, a time that was noisy and perhaps a little crowded, and create something new: silence, music, an instrument.

Maybe one day, when your Tamagotchi transforms into a butterfly, you’ll realize that care isn’t always about reminders and pixels. Sometimes, it’s just an off screen and a light that shines only for you.

Linear-arithmetic synthesis is based on sound formation. We’ve synthesized the perfect formula of facts and interest.

Thank you!