The revolutionary history of film stock

“Film is light, and it is alive, unlike the light of a phone screen.

A large portion of experimental cinema can only be viewed on film — and in no other way.”

Vladimir Nadein

The audience, spoiled by the wonders of progress, froze in astonishment. Seasoned Europeans forgot how to breathe. All because on the movie screen, a small distant dot suddenly turned into a roaring pile of metal and, with a screech, rushed straight at them. In just a moment, the hall could be flattened under the growling monster. The growling monster turned out to be a train arriving at La Ciotat station. The audience panicked. In those few seconds, reality and fiction merged into one, revealing the terrifying power of humanity’s greatest creation — the technology of cinema.

To shock the audience, the Lumière brothers needed only 50 seconds.

At that time, few people thought about the long road that led to the creation of the first motion picture in history.

The Living Beginning

Long before the era of movie cameras and Hollywood premieres, the world felt the need to preserve little stories to share them with future generations. In caves lit by the flicker of torches, history stood still on the walls. These were cave paintings — the earliest predecessors of cinema.

Ancient people, using simple tools, created “living” slides, showing moments of life frozen in time: here’s a hunter with a spear chasing a mammoth, and here — ritual dances around a fire. These ancient comics were always accompanied by sparks of curiosity and a thirst for self-expression, which gradually led humanity, hand in hand, to the invention of cinema.

Scene One: There’s an Inventor in Each of Us

Chances are, you too drew little faces in the margins of your school notebooks. And most likely, you also noticed that when you flipped the pages quickly, it created the illusion of movement. This same phenomenon was noticed by John Barnes Linnett, who in 1868 patented the term “kinematograph.” He realized that flipping through pages with drawn frames, each turn of the page created a new moment, a new emotion.

The kinematograph was just a notebook with a series of pictures drawn on its pages, but it firmly captured people’s imagination for decades. All because it marked the shift from static images to dynamic motion.

Scene Two: The Magic Lantern

“A small machine that shows in the dark on a white wall various ghosts and frightening monsters in such a way that someone unaware of the secret believes it is done by magical arts.”

César-Pierre Richelet

It’s hard to believe now, but there was a time when the world had no idea what social media was. Back then, people would gather around a “magic lantern” and watch pictures drawn on glass slides through it. The images on the slides would let light pass through and be projected onto a screen. This invention also brought humanity one step closer to the creation of cinema and demonstrated how light could bring images to life on a screen.

Scene Three: Slides, Discs, and the Barrel

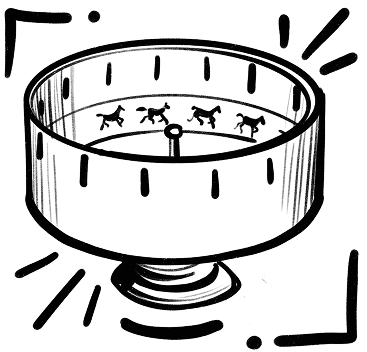

With time, transparent slides gave way to rotating discs. The scenes depicted on these spinning discs would flash by rapidly, creating a thrilling illusion of movement. To observe the shifting images, one had to peek through special slits.

Sometimes, a funny barrel with slots was used to show this kind of “movie.” Inside it was a strip of thin cardboard with drawn images. As the barrel spun, the pictures came to life and began to dance.

These pre-film animation devices, which created the illusion of motion by showing a sequence of drawings or photos, are called zoetropes, and they rightly deserve the title of precursors to film reels.

Scene Four: What Is Film Made Of?

At the heart of film lies a flexible and durable base made from a special type of plastic — strong and elastic cellulose acetate. This base plays the key role of carrying the light-sensitive components.

Back in the early 1860s, celluloid began to be used for signalograms — information carriers in the form of strips or sheets with recorded signals. The material showed promise, but it had one major flaw: it would constantly curl up, complicating the filming process. It wasn’t until 1887 that a solution was found — gelatin. A gelatin layer was applied to the back of the emulsion layer, giving the film stability. This gelatin layer held all the other film layers together, like the foundation of a house, and helped preserve its integrity during transportation. Film no longer tore during camera movement and stayed intact during post-production.

Photographic gelatin — essential for any film — was made by boiling cow bones and hides. The quality of the film varied depending on which cows were used and what they were fed. Some directors were very cautious in how they used their film stock, knowing that shooting even a short film might require the equivalent of a thousand live cows.

A signalogram can be compared to a canvas that lets light through. It has special layers inside which live tiny crystals — light catchers — made from silver and other substances. Their scientific name is silver halides. When light hits them, they light up and begin to change. These changes are invisible to the naked eye, but they are well captured by a film camera.

Light-catching structures vary across different film types. This difference determines what effects we’ll see in a movie, how bright the light needs to be during filming, and how grainy the image will appear.

The base layer of film protects its delicate parts like armor — shielding it from scratches, dust, and other damage. It must be transparent so as not to block the light from passing through and forming images.

Scene Five: Rainbow and Silver

Trrrrrrrrrrr. That rustling whisper was the sound of film in old movies—a sound of memory, an echo of history, a whole micro-world. A mix of silver nitrite grains, chaotically scattered across the frame, created a photographic effect that emitted a distinctive rustle. This rustling was especially noticeable in areas of solid color. Thanks to silver nitrite, the image gained a unique texture and depth, giving static objects a sense of life.

When actors spoke with their eyes, and color was only a dream

In the silent film era, directors were also painters. They shot in black and white and later transformed the footage into color using dyes. To make a film colorful, the filmstrip was dipped into vibrant dyes, creating hues that could convey the mood of scenes or the time of day. Early color films resembled an artist’s palette with a few shades rather than fully colored visuals.

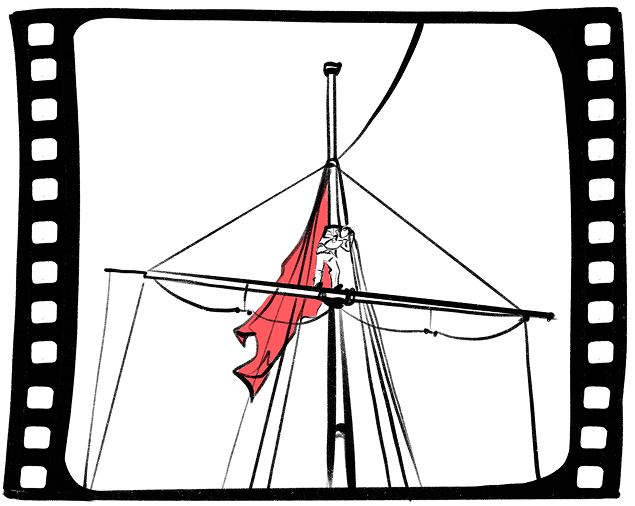

In 1925, during the filming of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, red couldn’t be reproduced on film. The director hand-painted each of the 108 frames with the flag using a simple brush.

Since the late 19th century, film adopted a process called “tinting.” This involved chemically treating black-and-white frames. The film didn’t turn into a rainbow, but it did gain an overall color tone that enhanced the on-screen atmosphere.

Blue perfectly suited night scenes. Yellow and orange conveyed sunny daylight. Red evoked romantic feelings, while green wrapped a film in mystery like a forest full of secrets.

Filmmakers of that time had to memorize recipes to prepare each film color.

To make red film, one needed:

▪️ 85 grams of potassium citrate for fiery inspiration

▪️ 5 grams of copper nitrate to add a hint of mystery

▪️ 6 grams of potassium ferricyanide for a passionate hue

▪️ 1 liter of distilled water

All ingredients had to be carefully mixed and dissolved. Then, the film was dipped into the red solution, where it would begin to glow with a bright purplish hue.

To create a yellow-brown tone:

▪️ 12 grams of sodium thiosulfate for warmth

▪️ 30 grams of alum for richness

▪️ 10 ml of 10% sodium chloride solution to brighten the color

▪️ and, again, water was used as the base

Blue was achieved with a mix of 5 grams of potassium ferricyanide and 1.5 grams of citric or tartaric acid.

But, as often happens with great ideas, reality stepped in—sound cinema arrived. Sound quickly captivated audiences, pushing color to the background. Filmmakers had to tackle the challenge of integrating sound directly onto film. They were forced to abandon tinting because dyes interfered with sound recording and made the film unusable. Color gave way to sound, leaving only ghostly memories of bright experiments behind.

Scene Six: The Black Square

No history of cinema would be complete without mentioning the great inventor Thomas Edison. At the turn of the century, during a boom in technology and cinema, filmmakers faced a frustrating problem—traditional 70mm film was too fragile under mechanical stress.

Edison took a bold step and split the wide film strip in two. Thus, a legend was born—the 35mm film format. It was stronger, more economical, and provided excellent image quality. This film became the “gold standard” that paved the way for mainstream cinema. Later, color and sound were added, and film became a multisensory experience.

For decades, 35mm film reigned as queen of professional cinema. To protect and transport it, special metal containers—called “cans”—were used. They kept the delicate medium safe during travels between studios or across the globe.

Scene Seven: Perforation

The distinct pattern of four holes along the film strip is called perforation. These holes ensured the stability of the filming process. Perforation worked like a gear gripping a chain, allowing the camera and projector mechanisms to capture, move, and hold each frame with incredible precision.

The film was pulled by a claw mechanism inside the camera. In its upward position, the claw’s teeth entered the perforation holes and dragged the film. In the downward position, the teeth retracted, allowing the film to stay still.

Together, these technologies eliminated the image jitter and instability found in earlier films. The film now moved smoothly and precisely, and the screen image stopped flickering. The overall film length increased, which also extended the duration of movies.

Frame Eight: The Golden Ratio

The golden ratio is surrounded by numerous legends and scientific myths. It has acquired an almost divine significance. The term “golden” was attached to it back in antiquity. It became a synonym for harmony, perfection, and beauty.

A sense of absolute harmony is embedded in every person: for instance, when we begin to shoot a landscape, we instinctively focus on a particular object, placing it at the center of the frame and building the whole composition around it — even if we know nothing about proportions or mathematical ratios.

That’s how life works, but mathematics has its own rules. The universal mathematical proportion of the golden ratio is approximately 1.618 and is denoted by the Greek letter φ (phi). It is closely related to a sequence of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding ones — for example: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, etc. If you divide any number in this sequence by the previous one, the result approaches 1.618.

The golden ratio appears in geometry as well. If you divide a rectangle with two horizontal and two vertical lines spaced equally, the intersections of these lines are the “golden points.” Placing key objects near these points helps create a visually appealing and balanced composition. These are the places that naturally draw the viewer’s attention and highlight the semantic center of the image.

If you look closely at frames from almost any movie, you’ll notice that the main character is not placed directly in the center but slightly off to the side — in the spot corresponding to the golden ratio. The horizon line is also not centered but set at a level that aligns with this proportion. In other words, the visible edge of the skyline is not right in the middle, but a bit higher. This makes the landscape appear more impressive.

In film editing, the golden ratio is used to determine the length and order of scenes, as well as to emphasize certain moments.

Frame Nine: Reels and Spools

During the era when 8mm film cameras were rapidly gaining popularity, film reels of various formats began to be produced worldwide.

A standard film reel operated at a speed of 25 frames per second and had a length of about 300 meters. This amount of film provided roughly 11 minutes of footage. As a result, projectionists in movie theaters had to change reels multiple times during a single film to ensure seamless viewing. While one projector was working, a second one would be loaded with a new reel. At the right moment, the projectionist would switch to the reserve projector, and the film would continue without interruption.

Sometimes, to allow the film to unwind smoothly during spool rotation, home video recorder reels were used. However, this method was rarely applied because the flexible material of the home reels didn’t hold the film securely. This caused the film to slip, drag, get tangled, or deformed — which could interrupt the screening at any moment. Gradually, film carriers began to be replaced by digital ones.

The End: A Living Substance

We’ve grown used to modern cinema. Movie screenings are no longer something magical or extraordinary. Today, we want new formats, new effects, and better quality in films — with no rustling, no interruptions, and no flickering.

A tiny piece of plastic infused with chemicals opened the doors to the thrilling world of cinema for many years. Now, it opens doors to history for some, and to nostalgia for others.

Behind the analog past lies an entire philosophy — even something like a shamanic ritual dedicated to the great art of film. Film is an analog artifact infused with the soul and warmth of cinema, something we cannot afford to forget in a digital world. It is alive, it breathes, it feels. And it’s always ready to pass on the essence of true cinematography.

The atomic fortress has fallen. And our hair stands on end!

Thank you!