Category: Materialization technologies

Architectural Chaos in Modern Cities

“Before building anything — listen to the city. Before demolishing anything — listen to your heart”

Norman Foster

Urban architecture is one of the main calling cards of any locality. Many tourists willingly visit new countries to see buildings from past eras, to touch history, or to see with their own eyes how diverse the art of construction can be. However, lately, a genuine architectural chaos has been unfolding in cities all over the world. Designers, architects, and builders, in pursuit of external aesthetics and fashionable trends, are erecting numerous buildings of futuristic shapes and flashy colors on the streets of metropolises, combining hundreds of styles in a single structure, and abandoning harmonious combinations, filling every square meter of the city with buildings that have no connection to each other.

Walks through modern cities increasingly cause visual discomfort for both locals and tourists, and a feeling that a randomizer participated in the construction. Why is this happening, and do we have a chance to dismantle this constructional mess in the name of genuine urban aesthetics? Let’s figure it out.»

Great buildings, like high mountains, are the creations of centuries

Look to the right: before you stands a tall, monumental building of red brick with an arched entrance, sharp spires on a black roof, massive stucco work on round windows, and marble inlays on the sides. In shape, the building resembles a festive cake crushed on the road more than a residential structure. Even an experienced architect would hardly be able to immediately determine which time and era this creation belongs to, and the average local resident would merely curl their lips in contempt, mentally dubbing the house “tasteless” and “a perversion.” And only the misunderstood genius, in the person of the one who built this house, would sigh dejectedly and say, “You’re the tasteless ones! And this, by the way, is modern architecture!” And would they be so very wrong?

Modern architecture, as a separate movement, emerged as far back as the 19th century, thanks to the nascent belief that creative expression should be free from historical baggage, and architectural forms should not be subservient to established standards as they were before. It was then that eclecticism appeared—the art of combining several historical styles and cultural elements from different eras in a single structure to create a completely new and original object of urban architecture.

Eclecticism has its origins in continental Europe, where different countries began creating new directions in urban construction one after another. In France, architecture in the Beaux-Arts style appeared; in England—the famous Victorian architecture; and in Germany, the era of Gründerzeit began. The architects and designers of that time strived for creative freedom and skillfully used their inspiration to create truly aesthetic and unusual buildings. But eclecticism sparked even greater interest in North America. The first American eclecticists who made a significant contribution to the development of this direction were Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim. Having received their education at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, they brought French Beaux-Arts to America. The main features of this style are considered to be symmetry, the monumentality of buildings achieved through the use of axial composition, and rich classical decoration in the form of columns, arches, cornices, and stucco work using modern materials like marble and light-colored stone. Eclecticism allowed for the reflection of American culture and history through unusual buildings, where the past and present harmoniously intertwined.

According to the principles of the new architectural style, skyscrapers and other large public buildings began to be erected, such as churches, courthouses, town halls, public libraries, and cinemas. The structures of that time are still considered some of the most significant in American architecture. However, some of them were demolished due to economic unprofitability, deterioration, and low comfort levels, for example, the original Pennsylvania Station building and the first Madison Square Garden in New York. The demolition of these landmarks of eclectic culture caused enormous dissonance among local residents, ultimately leading to the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Murderers and architects always return to the scene of the crime

Elements of eclecticism could be seen not only in cities but also aboard ocean liners, which at that time were the primary mode of transport for traveling abroad. The luxurious interiors of cabins and decks combined elements of traditional styles in an attempt to mitigate the discomfort of long months spent abroad and to create an illusion of established grandeur. At the same time, such vessels were used to transport colonists to unexplored regions of the world. The colonization of these territories contributed to the further spread of eclectic Western architecture, as the newly arrived colonists constructed buildings dominated by motifs of Roman classicism and Gothic.

In Asia, manifestations of eclecticism were not as widespread as in Europe and America. However, thanks to the Japanese architect Kingo Tatsuno, who studied at an American school, the main building of the Bank of Japan’s headquarters appeared in Tokyo in 1895. The project was executed in the Neo-Baroque style and inspired by the appearance of the National Bank of Belgium. The first floor of the building is almost entirely constructed of stone, while the second and third floors are built of brick, covered externally with thinly cut granite. The central dome features four columns at the front and two columns on each side wing. Today, the main building of the Bank of Japan is recognized as a significant cultural heritage site of the country.

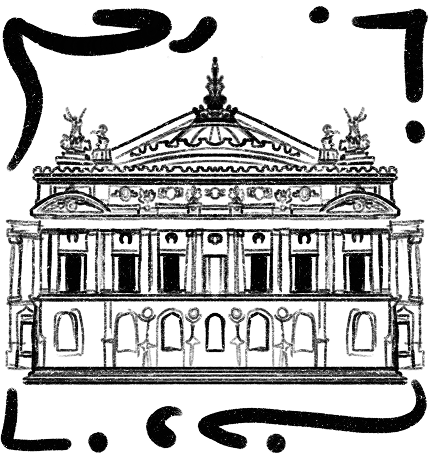

The true jewel of eclecticism can rightfully be called the Palais Garnier, the Paris Opera. It was built by Jean-Louis-Charles Garnier—a French architect and art historian. The Paris Opera is constructed in the Beaux-Arts style and continues the traditions of Baroque and the Italian Renaissance. Besides the Paris Opera, the most successful and striking buildings in Europe constructed according to eclectic principles are considered to be: the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, with elements of French Renaissance and Baroque motifs; the Berlin Cathedral, built according to Renaissance and Baroque principles; the Reichstag building in Berlin, combining elements of Neo-Renaissance and Baroque; the Natural History Museum and the Science Museum in Vienna, whose architecture blends Classicism, Baroque, and Renaissance; the Victoria and Albert Museum in London with elements of Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Gothic; and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, which combines Italian Renaissance and medieval architecture.

In Russia, the period of eclecticism is commonly divided into the “Nikolaev” and “Alexandrine” stages. During the reign of Nicholas I, one of the most famous eclectic architects was Konstantin Andreyevich Ton. Among his works are the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow, built in the Russian-Byzantine style; an apartment building on Malaya Morskaya Street in Saint Petersburg; and the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Krasnoyarsk, which was demolished in 1936. Ton’s Russian-Byzantine style did not take root in Russian architecture and completely disappeared after the end of the great emperor’s reign.

Another representative of the brilliant “Alexandrine” stage was the Russian architect Konstantin Mikhailovich Bykovsky. Among his creations are the Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker in Derbenevsky and the old Central Bank building on Neglinnaya Street in Moscow.

The master of late eclecticism in Russia is considered to be Alexander Nikanorovich Pomerantsev. It was thanks to him that the first multi-story apartment building of the merchant Gench-Ogluev appeared in Rostov-on-Don. The house has four floors, the last of which is special—a mansard. The building features elements of Gothic, Baroque, and Classicism. In the same city, according to Pomerantsev’s design, the eclectic building of the City Duma was constructed.

Eclectic projects that failed to harmoniously combine different styles were often criticized by professionals, especially those who opposed this movement. The most unsuccessful creations of the eclectics are considered to be the headquarters of the Union of Romanian Architects in Bucharest, The Flintstones House in Belgium, and a residential building made of flat panels in the Belgian city of Ostend. Interest in eclecticism began to wane in the 1930s, due to the transition to Late Modernism, Postmodernism, Brutalism, Art Deco, and strict Modernism. Despite this, echoes of eclecticism can still be traced in many contemporary urban buildings.

Architecture is merely a matter of proportions

Modern architects can now sleep peacefully; we have no more questions for them. But what are we, mere mortals, to do if, because of someone else’s architectural creative freedom, our heads spin and our vision blurs every time we step outside? Can modern architecture be harmonious, or are we forever mired in urban chaos? A little spoiler: everything is possible, but we’ll have to work hard. So, put on your helmets! Let’s clear up this construction mess together!

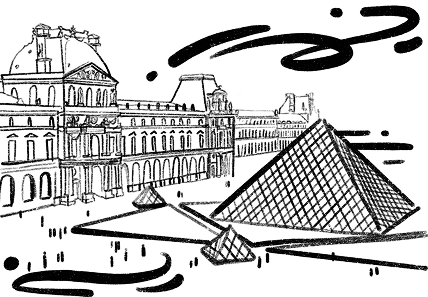

In architecture, as in any other art, there are certain “principles of compatibility” that many contemporary creators neglect. And in vain. To ensure that no one wants to gouge their eyes out at the sight of a new building, it is crucial, first and foremost, to maintain unity of scale. This means all elements must be proportionate to each other, regardless of their historical origins. Color coordination is also very important, as using a unified color palette helps harmoniously combine even disparate elements. The third significant principle is functional justification, under which every architectural element should serve a practical purpose and not be created just “because I felt like it.” Nor can we forget about material connection—combining materials in a way that is technologically justified. For instance, glass and metal go together quite well; their synthesis is quite appropriate in architecture and often serves to create transitional elements between historical and modern parts of a building. To see this for yourself, one only needs to look at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

The historical architecture perfectly harmonizes with the 21-meter glass pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre, built in 1989 by architect I. M. Pei. This pyramid now serves as the museum’s entrance and a bright foyer, through whose transparent walls the Baroque and Rococo outlines of the art museum’s ensemble can be seen.

Overdoing it is bad not only in cards but also in construction, so one should not overload a building with details and stylistic elements. This often leads to the loss of the overall concept and the building’s identity. Adding new elements to historical architectural units is appropriate, but only if it does not violate the original proportions or distort the external appearance. And, of course, we must not forget that any building is constructed primarily for people, meaning its space should be as functional as possible. These mistakes can be avoided thanks to modern 3D modeling programs, where a complete virtual projection of the future creation can be made, all its strengths and weaknesses assessed, and adjustments made before construction begins.

A doctor can bury his mistake, an architect can only advise growing ivy

“So, if you’re so smart, maybe you can tell everyone which architectural styles go well together?” some novice architect might ask us indignantly. And we’ll just go ahead and tell them! Here’s an architectural cheat sheet.

Let’s start with classicism. This style is characterized by strict geometric forms, clarity of lines, rigid proportions based on the mathematical principles of the “golden ratio,” a light color palette, and the use of porticos—entrance groups with columns that create a solemn impression. Classicism pairs well with elements of eclecticism, for example, with the lavish ornamentation of Baroque or the military attributes of the Imperial Empire style. Classicism also often looks organic with neoclassical styles.

And what about Baroque? What best complements its complex forms, interweavings, smooth transitions from one plane to another, bright colors, visual illusions, and the alternation of convex and concave surfaces with a sense of deep volumes? For instance, with the aforementioned classicism. In the past, French architects often combined Baroque and classicism in the design of urban mansions and country residences. Baroque can also be paired with Rococo, Neoclassicism, and Gothic.

Now let’s talk about Art Nouveau. It is characterized by asymmetry in compositional and volumetric solutions, rounded facades, the use of natural motifs, and the unity of exterior and interior space. Art Nouveau harmonizes well with elements of traditional Russian architecture, for example, with motifs of ancient Russian architecture, wooden structures, and folk ornaments. Another option is combining Art Nouveau with religious buildings or with industrial and commercial structures.

Finally, let’s look at High-Tech. The most distinctive features of this style are the use of modern materials—glass, metal, concrete, and plastic; clear, strict lines; cubic or rectangular forms; large glazed surfaces; exposed structures; minimalist decoration; high technological integration; and a neutral color palette. Because of this, High-Tech perfectly complements Minimalism, as both styles focus on organizing functional yet simple space.

High-Tech can also be combined with the Scandinavian style, which can add coziness to technological austerity, or with the loft style, if the goal is to give High-Tech visual power through open-plan layouts and brutal metal and concrete elements.

Architecture is the art we live in

To conclude, let’s try to glimpse into the future and predict which architectural trends await us in the near 2030. Already, there is a clear emphasis on the sustainability and multifunctionality of modern buildings. Examples of such changes can be seen in major cities like Copenhagen, Amsterdam, and Singapore, which are actively implementing sustainable and innovative approaches to urban planning.

Green roofs and facades, rainwater harvesting systems, and the use of renewable energy sources hold an important place in new urban projects. For instance, the facades of the Bosco Verticale residential complex in Milan are adorned with greenery and flowers. In terms of multifunctionality, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Bloomberg headquarters in London lead the way. Their spaces are used for both cultural events and offices, as well as other public areas.

We can confidently say that by 2030, architectural structures will increasingly be built from biological and very lightweight materials with a low carbon footprint, while the forms of buildings and their color palettes will predominantly be calm, natural, and organic. The most popular style in construction will become bio-tech—the complete opposite of high-tech. Perhaps this will help rid our cities of urban chaos, find a golden mean, and set a trend for genuine architectural aesthetics, rather than uncontrolled self-expression by creators.

“The architect who deserves the highest praise is the one who knows how to combine beauty with convenience for living in a building”

Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini

The double-slit paradox awaits you! Learn from particles how to act mysteriously and unpredictably.

Thank you!