Category: Materialization technologies

From Samhain to the Day of the Dead: The Evolution of a Pact with the Unseen World

“Everyone has Halloween every year. I have it every night”

Ozzy Osbourne

October 31st. The darkest and most mystical day of the year—Halloween. During this eerie celebration, the streets are wrapped in thick fog. On doorsteps, pumpkins glow with bright yellow light, their carved grimaces casting long sinister shadows on the pavement and walls. The air carries the scent of decaying leaves and sweets, mixed with smoke from bonfires and spices. Figures in terrifying costumes emerge from the darkness to frighten those who cross their path, then knock on doors and offer a choice: trick or treat…

The atmosphere of this night cannot be confused with any other—it thrills, fascinates, intrigues, and makes the blood freeze in one’s veins. But where did this strange tradition of dressing up as monsters come from? Is Halloween the only mystical holiday of its kind, or are there others in the world even darker and more bizarre? On the eve of this haunting celebration, the editorial team of The Global Technology conducted its own investigation—and found the answers to all of these questions.

“Pumpkins with carved, evil smiles stood in the yards, their candlelight flickering in the darkness, creating the feeling that the night itself was alive with a sinister soul”

Tim Burton, The Nightmare Before Christmas

Halloween first appeared around the 10th century BCE. Back then, it was called Samhain. Originally, it was a Celtic festival marking the end of summer and the harvest season— and the beginning of winter and the New Year. The Celts believed that on the night of October 31st, the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead grew thin, allowing spirits of the departed to return to Earth.

To protect themselves from restless ghosts, people wore animal skins and terrifying masks. It was believed that in such disguises, evil spirits would mistake humans for their own kind and pass by. Thus were born the first Halloween costumes.

With the spread of Christianity, Samhain was reinterpreted as the eve of All Hallows’ Day—All Hallows’ Eve, later shortened to Halloween. This is when a new tradition emerged—souling. The poor would dress in special clothes and go door to door offering to recite prayers for the souls of the dead relatives of the household, to help them escape purgatory sooner. Normally, priests performed such rites for a fee that many could not afford—so on All Hallows’ Eve, the poor were in high demand. In return for their prayers, they received a soul cake—a honey-oat pastry marked with a cross. If one needed to release more than one soul, as many cakes were baked as souls to be freed.

After the 16th century, souling turned into more of a playful performance—people went door to door singing loudly and demanding treats in exchange for silence. Over time, this evolved into the modern children’s custom of trick-or-treating—when kids can, for one magical night, demand candy from strangers, whispering the spooky question: “Trick or treat?”

However, there was a time in the United States when these “tricks” went too far. Children in their festive frenzy smashed shop windows, soaped windows, painted walls, stretched ropes across sidewalks, threw flour at passersby, and even made small homemade bombs. The first rebellion against such chaos came from the town of Anoka, Minnesota, in 1919.

The morning after Halloween looked like a battlefield: overturned outhouses, wagons on rooftops, and cows wandering through the streets—and even into the county jail. There were reports of buckshot fired at mischievous children. During World War II, the mischief was seen as borderline sabotage—pranks like soaping windows or ringing doorbells were frowned upon. City officials decided to organize community festivals to distract children from vandalism. In 1942, Chicago’s city council even proposed replacing Halloween with Conservation Day—though the idea was never adopted.

“When the darkness fell completely, the trees seemed alive, and the shadow of the long night thickened around, as if the night itself wished to claim all within its darkness… The scent of decaying leaves and earth filled the air, and the soft whisper of the wind, like the murmuring of spirits, made one feel that something ancient and unseen was near”

Washington Irving, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

Despite its popularity in the U.S. and parts of Europe, Halloween has many “relatives” around the world. Perhaps the most famous of them is The Day of the Dead—Día de los Muertos in Mexico. Celebrated annually for two days, it begins on November 1st, when Mexicans honor all saints, and continues on November 2nd, when they commemorate their departed loved ones. Before the celebration, homes are cleaned and decorated with special altars covered with candles, bright sugar skulls, flowers, food, and photos of the deceased. The more elaborate and beautiful the altar, the sooner, it is believed, the spirits of loved ones will visit and the longer they will stay.

In the Mexican city of Oaxaca, processions of people in colorful costumes and skull makeup fill the streets and cemeteries for all-night rituals. Preparations for the festival take weeks—people buy ornate hats, visit makeup artists, bake tamales, and learn ceremonial dances. Despite its somber roots, the Day of the Dead is celebrated joyfully—it is a family gathering, a moment to speak of immortality and love beyond death.

In Bolivia, there is also a local counterpart—the Day of Skulls or Día de las Ñatitas, celebrated on November 8th. Many Bolivians keep the skulls of deceased relatives—up to the fifth generation—at home on a high shelf as a sign of remembrance and connection. On this day, when the boundary between the living and the dead grows thin, families take out the skulls, dress them in wigs, hats, glasses, flowers, jewelry, even sprinkle them with glitter, and display them proudly on tables or doorsteps. In ancient times, the celebration was even darker: families would exhume the mummified bodies of ancestors and dance with them in cemeteries—or take them for a walk through town.

“And the house of Usher looked as if terror itself dwelled within its walls; its windows—like empty eyes, and the branches clutching its facade—like skeletons entwined around a skull”

Edgar Allan Poe, The Fall of the House of Usher

In Peru, in the city of Puno, the festival La Diablada takes over for an entire week beginning November 2nd—a wild dance of good and evil, demons and ritual frenzy. Locals dress as devils, paint their bodies and faces, mark their necks with crimson crosses and horns, and dance madly on the shores of Lake Titicaca to the beat of drums. The celebration is meant to drive away evil spirits that, according to legend, wander the earth for a week under the command of their Dark Lord. By the festival’s end, there is no trace of uninvited guests—frightened away by the spectacle itself.

In China and other parts of Asia, the Hungry Ghost Festival is celebrated on the 14th or 15th night of the seventh lunar month. During this time, the gates of the underworld open, and the souls of the restless dead roam the earth. To appease them, people burn paper money and make offerings of food and symbolic gifts. It is forbidden to marry, bathe in open water, start new ventures, whistle, or visit nightclubs—for fear of offending the wandering dead. In theaters, special front-row seats are reserved and marked with red thread—for ghostly spectators.

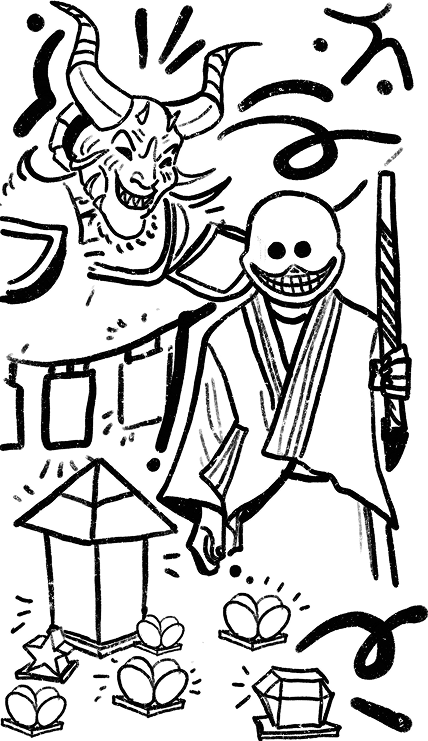

In Japan, there is a gentler counterpart—the Obon Festival held from August 13th to 15th. It is believed that during Obon, the souls of deceased ancestors return to visit their families. Homes, streets, and cemeteries are decorated with chochin lanterns whose light guides spirits to and from the world of the living. Inside each home, families place an altar with photos and favorite foods of their loved ones. During Obon, people perform the Bon Odori dance—a graceful circle of gratitude to their ancestors. At the center stands a wooden tower—a yagura—where musicians and singers perform as dancers move rhythmically around them, waving fans, flowers, or straw hats.

“The fog hung low over the ground, thickening around the house, turning everything into a ghostly maze of shadows where nocturnal creatures hid in the dark”

Edgar Poet Wallace Crocker, The Candlestick

Should one fear evil spirits on Halloween—or celebrate them with open arms? That question lies far beyond the realm of science. Yet the very existence of this ancient cultural code, its worldwide persistence, and its psychological impact on society—all deserve serious study.

Our editorial team respects every mystical tradition—and so we end with the only question that truly matters…

Trick or treat?

“Morning. Halloween. Pumpkins rot. Leaves burn. Black cats mate in the alleys like rats. It seemed we felt no fear. As if we had already died—and had nothing to lose. Or maybe, because we lived so passionately, loved life so fiercely, we imagined ourselves immortal, drawing power from our mad devotion to science. Or perhaps, we simply went insane”

Randy Steckel, Flatliners

It seems we’ve found a way to decode Einstein’s unknown equation.

Thank you!