Category: Materialization technologies

How glasses changed the way we see

“— How do blind moles find their way underground, where to dig?

— They have a good sense of smell, they can sense where the carrots grow.

— And why do they need carrots?

— For their eyesight”

from Anecdots.net

Before you start reading this article, cover one eye with your palm, look at an eye chart, and say which line you can see clearly. If you can easily read the entire chart or at least most of it, congratulations: you’re probably one of the lucky ones who always see the world in focus. But if you had trouble reading the optometrist’s chart, close both eyes and rest them for a few minutes. The article won’t go anywhere, and your rested eyes will surely thank you.

Out of the five senses, vision is the most important for humans, because about 90% of information about the world around us comes through our eyes. Yet every year, more and more people complain about vision problems, and the “blur effect” built right into the human eye is becoming a common issue for the modern generation.

Gone are the days of cruel nicknames like “pointy-head” or “four-eyed kid.” On city streets now, more and more people squint every time they need to see something farther than a meter away. Anyone who has visited an eye doctor at least once has heard: “It’s all because of your gadgets!” or even “Your tall height is to blame!”

Specialists, as a solution for vision problems, most likely suggested looking into the distance more often, surrounding yourself with green colors, and eating blueberries around the clock.

Could it be that God wronged me by denying me the sight of the sun in the sky?

Scientists still can’t agree on why people today are losing their eyesight at such an alarming rate. Some say that glasses and contact lenses are like “crutches” that prevent nature from doing its natural selection — filtering out those with poor vision. Back in the day, a person with bad eyesight stepping out of their cave would inevitably fall into a deep pit or become lunch for a predator. But with the invention of glasses, those with weak eyesight suddenly got a leg up: they could live, reproduce, and pass on their poor vision to the next generation without worry.

Other scientists argue that our eyes were originally “designed” for hunting, not for endless PowerPoint presentations and scrolling through social media. Nature gave us sharp dynamic vision to see far away — but now our eyes suffer because we stare at objects just 30 centimeters from our face for hours on end. Endless surfing through web pages breaks the delicate balance between eye accommodation and relaxation, leaving us “stuck” in close focus like a camera that can’t zoom out.

Many believe the root of the problem lies in modern education: school kids and students develop nearsightedness because they’re forced to read tons of books and write long notes while hunched over their desks, straining their eyes until vision noticeably worsens. The digital age brought even more eye troubles than any previous era, thanks to those blue smartphone screens that dry out eyes, cause fatigue, and reduce blinking. Some conspiracy theorists even claim gadget makers deliberately design these screens to later sell glasses, contacts, eye drops, and costly surgeries to the masses.

Some scientists go even further and suggest that our widespread vision problems might be the consequence of humanity entering the next evolutionary phase — “Homo Pixelus.” According to this theory, the human eye is losing its universal function and adapting to a new 2D world, where high-tech “new eyes” won’t just see but will turn us into beings capable of creating our own realities — instead of merely focusing on our immediate surroundings and settling for what’s around us.

Most likely, the person who can provide a clear answer to why vision is deteriorating so widely among the modern generation will immediately receive a Nobel Prize and secure a life of comfort. But at the moment, this problem remains unsolved, and to even begin to understand the reasons behind poor eyesight in people, it’s worth looking back at how it all started.

To wear glasses, it’s not enough to be smart—you also have to have poor vision

In ancient times, when thinkers and great minds already existed but glasses were still unimaginable, the topic of vision problems was a favorite subject in social circles. Yet, as soon as a wise person accumulated a hefty amount of knowledge by old age, their eyes would fail them, preventing them from recording yet another wise thought on papyrus.

The ancients quickly noticed the connection and declared: if you see poorly, it means you are smart. It’s worth noting, however, that less intelligent people also suffered from vision problems. In their case, farsightedness was considered a punishment for “stupidity,” and restoring their sight was deemed unnecessary.

However, the complaints of the visually impaired masses led nowhere, and for a long time, the issue of poor eyesight remained just a topic for loud debates.

Only in the 11th century did the Arab scholar Ibn al-Haytham describe, in his works, a lens that could help people suffering from farsightedness (those who have difficulty seeing objects up close, despite seeing well at a distance). But the scholar was unable to properly craft the lens.

The thing is, with farsightedness, light rays focus not on the retina but behind it, causing nearby objects to lose sharp outlines. To correct farsightedness, convex converging lenses were needed—these lenses could focus light rays in front of the retina and restore clear vision to the person. However, inventing such a lens required deep knowledge of optics and lengthy experiments, so no one’s vision improved in the 11th century. Nor in the next one.

But in the 13th century, Ibn al-Haytham’s works were translated into Latin, sparking interest among other scholars.

Europeans suffering from vision problems initially began using polished pieces of crystal or glass, holding them up to one eye. This trick was first noticed around the year 1000 among monks who copied manuscripts. Of course, pressing a tiny piece of glass to the eye was uncomfortable, but in the absence of alternatives, people made do.

By 1300, Venice introduced a standard for making “reading stones” in the form of a monocle—a special convex lens for one eye that allowed people with farsightedness to read small print without having to hold the book across the room. The lenses were often made from stones considered sacred: rock crystal, amethysts, and topazes. Thus, “restoring sight” carried a sacred meaning as well.

A few decades later, in Provence, someone had the idea to join two lenses with a bridge and create the first prototype of modern eyeglasses. This invention was called “pince-nez”—small glasses that could be perched on the tip of the nose. The first to try them were, of course, nobles. For example, on a 1352 fresco, Cardinal Hugo of Provence is depicted wearing pince-nez, while his entourage still used monocles. When pince-nez became widely available, farsighted aristocrats adapted them by attaching a stick or a chain so they didn’t have to hold them on their nose constantly.

One way or another, people with farsightedness were thrilled with these inventions—but it later became clear that different vision problems require different types of lenses.

After many experiments, in the 16th century concave diverging lenses were invented to correct myopia — a vision defect in which people cannot see anything beyond the tip of their nose. This type of lens allowed light rays to be spread out evenly so that they would focus exactly on the retina, rather than intersecting in front of it, which previously left only nearby objects clear.

We were given eyes, but not vision. We look into emptiness, and cannot see the road ahead.

In the 18th century, the slow evolution of eyeglasses led to the creation of bifocal lenses — double lenses of different shapes combined into a single frame. Such lenses were used by people suffering from astigmatism — a vision disorder where light does not focus in the center of the retina because of the elongated shape of the lens and cornea. Instead, the light scatters either behind or in front of the retina, causing a person to suffer simultaneously from both farsightedness and nearsightedness. Before bifocal lenses, people with astigmatism had to wear two pairs of glasses and switch them depending on the situation. But the newly invented lenses solved this problem: to see something nearby or far away, it was enough to simply shift the gaze up or down. Later, trifocal lenses were invented, designed for distance, near, and intermediate vision. These lenses were not split by a line like bifocals but had visual zoning: the upper part of the lens was for distance vision, the middle for intermediate, and the lower part for near vision.

However, solving one problem always gave rise to another: vision defects became more frequent and developed faster than people could find ways to correct them. Some began to suffer from retinal detachment — a condition in which a space filled with fluid forms between the retina and the eye. People with this condition often completely lose their vision with no chance of recovery. Even today, retinal detachment can only be corrected in its earliest stages and requires lifelong adherence to certain restrictions.

Another serious eye disease is glaucoma — vision impairment caused by constantly high pressure inside the eye. Besides worsening vision, glaucoma is accompanied by severe headaches, redness and pain in the eyes, dizziness, nausea, and the appearance of “rainbow halos” around lights. Wearing bifocal or trifocal lenses is strictly forbidden for people with glaucoma or retinal detachment, which significantly complicates the lives of those suffering from multiple vision problems at once.

The most important thing is to feel like a seeing person

In the mid-19th century, ophthalmology—the science of the structure and function of the eye—was separated from surgery and became an independent discipline. In the same century, the evolution of eyeglasses reached a new level: in 1887, Czech scientist Otto Wichterle created the world’s first contact lens made from transparent flexible glass that covered the entire surface of the eye. Then, in 1888, Swiss ophthalmologist Adolf Fick improved Wichterle’s lenses so that they could stay on the eyes by themselves. This invention allowed people to get rid of uncomfortable glasses, which often caused discomfort or even self-consciousness.

The foundation for creating lenses was laid by the research of Italian scientist and artist Leonardo da Vinci, who in 1508 drew a diagram of an optical device shaped like a sphere filled with water. Da Vinci’s idea was that a person with poor vision who looked through this sphere would see better. He never saw this invention realized in his lifetime, but centuries later his idea became the basis for the creation of contact lenses. In 1637, French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes suggested using a tube filled with water with a magnifying glass fixed at one end as a lens. This idea worked but was very dangerous: the tube had to be pressed directly against the eye, risking damage and infection. Until the 1920s, scientists actively searched for safer and more suitable materials to make contact lenses, after which mass production began in Germany.

In the 1940s, inventor Kevin Touhy from New York created lenses that were much smaller than their predecessors, making them more comfortable to wear. However, the hard plastic used to make these lenses still irritated the eyes and caused discomfort, especially with prolonged use.

In the 1950s, scientists Otto Wichterle and Drahoslav Lim synthesized a new material that absorbed water, becoming very soft and elastic. From this polymer, the world’s first soft contact lens was made—one that did not irritate or injure the eye and was comfortable to wear. However, the variety of eye shapes and individual features required further improvements, so in the 1970s scientists in the United States developed special hydrogel materials that gradually began to be used for manufacturing contact lenses.

In 1999, breathable silicone hydrogel contact lenses appeared. Thanks to their high elasticity and oxygen permeability through the material, these lenses proved to be very comfortable. Today, contact lenses are very thin, transparent, soft films placed on the surface of the eye. They provide people with poor vision high-quality sight and maximum comfort for their eyes. Gradually, new features are being added to contact lenses: modern colored lenses allow people to change their appearance, and some lens models can even measure blood sugar levels. There are even special overnight orthokeratology lenses (or OK lenses) that help people with mild vision distortions restore their eyesight while they sleep. These lenses safely reshape the front surface of the cornea during sleep, returning it to its anatomical position, which is maintained throughout the day.

Ordinary vision is only a hindrance to inner vision

In 2015, American scientists from the company Argus Retinal Prosthesis developed bionic eyes — an electronic prosthesis called Argus II, which uses a camera to capture information from the outside world and transmits it to a special device. The device converts the signal into an electrical impulse and sends it first to a microchip implanted in the eye, and then to the retina or the cerebral cortex, restoring vision to the person. The estimated cost of implanting the Argus II prosthesis is over $150,000, so only wealthy people can afford it. However, bionic eyes are not yet very popular: after surgery, patients achieve visual acuity of no more than 0.05 diopters, which only allows them to distinguish object outlines, light, and have some spatial orientation.

It is also worth mentioning the neurochip called “Telepathy,” which, in theory, will be able to painlessly restore vision and hearing in people and eliminate the consequences of head and spinal cord injuries.

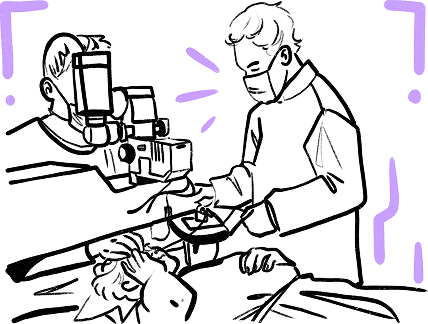

Currently, the most effective way to restore vision is considered to be laser correction, which was invented by Dr. Stephen Trokel in 1983. The first lasers for correction allowed surgeons to reshape the cornea and give it new optical properties to improve or restore vision. These procedures were called PRK—photorefractive keratectomy—but they had many drawbacks, ranging from long healing times, photophobia, and tearing to the development of corneal haze.

In the 1990s, a more advanced technology called LASIK (Laser-Assisted In Situ Keratomileusis) appeared in the USA. During the procedure, a special mechanical keratome made a partial cut through the sensitive superficial layers of the cornea. Then, this upper layer was lifted, and an excimer laser reshaped the lower layers of the cornea. Afterward, the corneal flap was returned to its place, where it reattached fairly quickly. Recovery after this surgery was significantly faster, and the discomfort was much less compared to PRK. However, the mechanical cutting with the keratome was not very precise, as the mechanical device often caused inaccuracies and cut varying amounts of corneal tissue, which could lead to even more serious vision problems.

The next stage in the evolution of these inventions, between 2005 and 2010, was Femto LASIK — a femtosecond laser that works on the principle of micro-explosions. This method greatly reduced errors during the incision and lowered the risks of the operation. Moreover, within a day after the surgery, the patient experiences no discomfort.

The newest and safest laser vision correction technology, ReLEx SMILE, appeared in 2020. This technology retained the femtosecond laser but changed the technique of corneal incisions. Thanks to ReLEx SMILE, a negative corrective lens is immediately formed within the corneal layers. It somewhat resembles a real contact lens made from corneal tissue but is much thinner. After the lens is formed, the laser makes a micro-incision about 2 mm in size, through which the excess corneal tissue shaped like the lens is removed. Because the micro-incision is now only 2 mm instead of the 20 mm incision used in Femto LASIK, the recovery and healing process has been greatly shortened, along with the side effects of healing.

“Yes, vision is three-dimensional! I know that. But…

Perhaps the fourth dimension is still given to us.

For in every hour of our lives, no matter how we stir it,

We still have the vision of the soul in reserve.

And if the essence is hidden deep and the night is pitch dark,

The eyes may struggle. But the soul—

It will pass through any wilderness clearly and truly,

While three-dimensional vision is only for souls that are blind…”

Poet Sergey Grigoryevich Ostrovoi

Modern technologies help make life easier for people with low vision, offering a wide selection of glasses and contact lenses, many of which cause virtually no discomfort. Vision restoration surgeries yield good results, returning perfect eyesight to many people with minimal risks and side effects. And who knows—perhaps in the near future, technology will advance so much that eyesight can be restored in just one second using some kind of chip or device that resets our eye’s current settings back to the basics?

In any case, vision must be protected, and we should strive for a world where your eyes don’t need glasses, lenses, or chips to see. But if fate decides otherwise, it is important to remember that the most important things cannot be seen with the eyes—only the heart sees clearly.

According to the Big Bang Theory, the Great Explosion of discoveries starts right now.

Thank you!