How editing shapes what we see and feel

“What I enjoy most is the editing process—assembling fragments into a whole and giving them meaning.”

Christian Marclay

In a dark editing room, frames flicker by: the hero steps out of a car, now he’s entering a building. One move of the mouse, and the hero notices a stranger. It took hours to shoot this scene, but on screen, it all happens in seconds. Editing works wonders—compressing and stretching time, colliding thoughts, and bringing emotions to their peak. Editing directs perception, shaping the very essence of cinematic language. It holds the invisible mechanism that makes a film engaging, tense, or extraordinary.

The Psychology of Perceiving Edits

“The less the camera can capture what you see in the scene, the more editing you need.”

Tom Anderson, American director, screenwriter, producer, and actor

When we watch a movie, our brain is hard at work, trying to assemble all the elements into a coherent picture. It analyzes every detail, like a detective, to understand how events are connected.

Editing plays a key role in this process because it directly influences our perception of the film. To understand how it works, we must explore how the brain processes visual information. We observe objects, interpret them, and relate them to past experiences to make sense of what’s happening. For example, if we first see a person’s face and then their gestures, we automatically link the shots and understand what the person is feeling or doing.

This perceptual process can be explained through Gestalt psychology, which posits that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. It’s like looking at a painting: individual brushstrokes matter, but only together do they form a meaningful image. Editing in cinema functions similarly, connecting disparate shots in a way that evokes specific emotions or associations in the viewer. For instance, showing a gunshot followed by a character’s face may elicit fear or tension—even if the character shows no clear expression of horror.

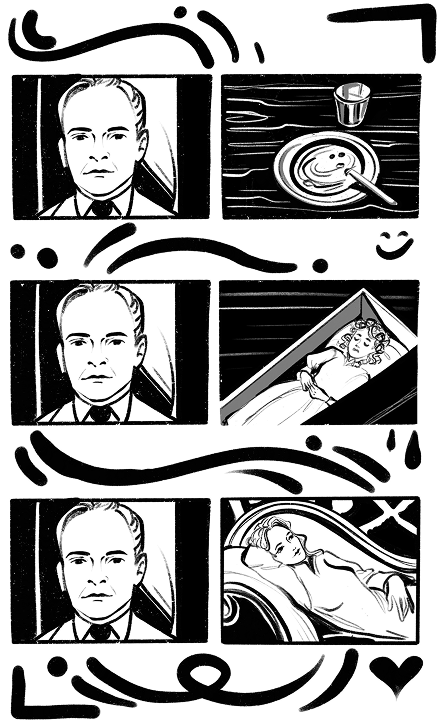

This effect was vividly demonstrated by Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov. In his experiment, he used the same neutral facial expression of an actor but paired it with different images:

·️️ After a shot of a bowl of soup – viewers saw hunger;

·️ After a coffin – they perceived grief;

·️ After a woman – they sensed love.

The Kuleshov Effect is explained by the fact that we don’t perceive emotions in isolation—we always interpret them in the context of surrounding factors. Thus, editing in cinema doesn’t just link shots together; it creates new meaning by manipulating the viewer’s emotions and thoughts.

Moreover, context is not only what we see on screen, but also what we expect to see. For example, if a character in a film has been repeatedly shown doing dangerous things, and we see that character holding an object, our brain automatically anticipates something threatening in the next shot.

How Editing Creates a Coherent Story from Separate Shots

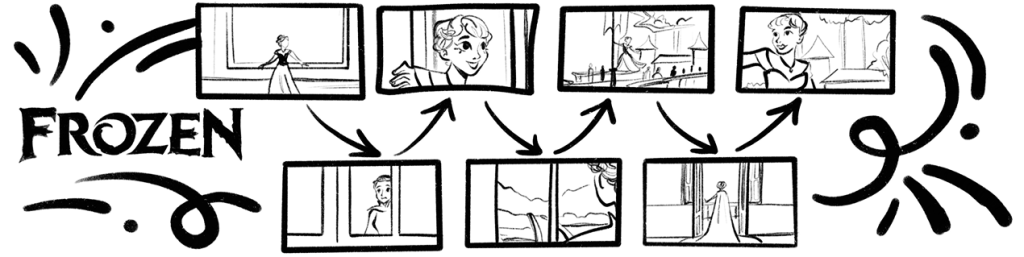

Our brain automatically fills in missing information. In real life, we perceive the world as continuous, but our eyes only capture discrete moments. The brain connects these fragments, creating the illusion of continuity.

Editing harnesses this mechanism, leading viewers to perceive separate shots as part of a logically connected narrative.

Shot 1: A man picks up an apple.

Shot 2: His wife asks him something, and the camera shows her angry face.

Shot 3: The man is already chewing the apple.

We never saw what actually happened between the shots, but the brain automatically fills in the gap.

This effect is known as perceptual filling-in, and it allows editors to work with cuts and omissions that the viewer doesn’t even notice.

Neuropsychologists have discovered that the visual cortex of the brain does not process each frame as a separate event but instead creates a continuous stream of perception. This explains why cuts in editing feel so natural to us.

Neurophysiology of Editing Perception

When we talk about editing, we often focus on its artistic or psychological aspects, forgetting that editing also impacts viewers from a biological standpoint.

The visual cortex of the brain, responsible for processing visual information, works at incredible speed, analyzing every frame. Each time a shot changes, the visual cortex adapts to the new image. But for the brain, a change in frames is an active process of perception and connection-building. While watching a film, the brain tries to predict what will happen next, relying on past experiences.

When we watch a movie with rapid editing, the brain enters what is known as an “alert mode.” It must constantly adapt to new data, increasing activity in the visual cortex. This effect can be compared to how the brain reacts to sudden changes in the environment—such as movement that grabs our attention.

Additionally, the amygdala, which is responsible for emotional responses, also plays a significant role. When we see a striking and unexpected editing choice—for example, a sudden scene change where the protagonist faces danger—the amygdala becomes activated. It triggers various emotional reactions depending on the context of the scene. This explains why we feel stressed during fast-paced editing in thrillers or joyful when watching upbeat music videos.

Interestingly, editing can also be used to manipulate our perception by creating cognitive illusions. For example, when we are shown alternating scenes that aren’t directly connected, our brain still tries to make sense of them. We can look at two entirely different shots, and even in the absence of clear logic between them, our brain will try to establish a link.

Classification of Editing Techniques

Linear Editing

Linear editing is the most traditional and logical way to tell a story. Imagine explaining your day to a friend: you woke up, had breakfast, and went to work. It’s clear and straightforward, with no surprises.

That’s how linear editing works in cinema: events unfold in chronological order. This technique is widely used in adventure films, classic detective stories, and traditional dramas—anywhere it’s important for the audience to follow the storyline without confusion.

For example, in Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark, the protagonist goes through a series of challenges step by step, and the viewer always understands where he is and what’s happening.

However, linear editing doesn’t always create strong emotional tension. It can feel like telling a joke too slowly: “Here comes something funny. Get ready. A joke.” The effect is immediately lost.

Parallel Editing

Parallel editing shows multiple events happening at the same time in different locations. This technique heightens tension by allowing the viewer to sense how different storylines are gradually converging.

In The Godfather, parallel editing is used in the scene where Michael Corleone attends a child’s baptism while, at the same time, his men are eliminating the family’s enemies. The contrast between the peaceful church ceremony and the violent murders creates powerful dramatic tension.

Another striking example of parallel editing is The Dark Knight, where Batman races to save one victim while we simultaneously see another in danger elsewhere. The constant switching between these scenes intensifies the suspense, making us worry about both situations at once.

Intellectual Editing

Intellectual editing, or montage of attractions, operates not just on the level of events, but on the level of associations. Meaning arises not from the individual shots, but from their combination.

This principle was famously used by Sergei Eisenstein in Battleship Potemkin. In the iconic Odessa Steps sequence, the tension builds through editing that alternates between close-ups of a screaming baby, the steps, fleeing civilians, and ruthless soldiers shooting at them. The contrasting images create shock, resonance, and a deep emotional impact.

Rhythmic Editing

The rhythm of editing influences the perception of a scene just as much as the imagery itself. Rapid cuts create tension, while a slower pace allows the viewer to absorb the details.

Normal rhythm: the character pushes off, falls, and lands. The viewer perceives time realistically.

Accelerated editing: the character pushes off and lands. These actions happen almost instantly.

Slowed-down editing: first, we see the character’s face, then their foot hanging in the air, hair flying upward, and tense hands. The fall lasts several seconds and feels like an eternity. This effect is also known as “psychological time.”

Our perception of time depends on the amount of information being processed: if the scene is filled with many details, editing makes us analyze them sequentially, stretching the sense of time. If there’s little information, the event feels like a fleeting moment.

Combining Techniques and the Impact on the Viewer

Films that rely on only one editing style are rare. Directors usually combine different techniques to achieve a desired effect. In Christopher Nolan’s Inception, we see parallel editing (multiple dream layers), rhythmic editing (tempo acceleration during critical moments), and intellectual editing that leaves viewers questioning what’s real.

Editing can be compared to cooking—black pepper alone won’t make a dish tasty, but when combined with salt, herbs, and lemon juice, it can become a masterpiece. Similarly, in film, the more skillfully editing techniques are blended, the stronger the emotional impact on the audience.

The Tricks of Editing

A close-up of a face makes us read the character’s emotions; a detail shot of a hand gripping a gun shifts our focus to the action.

If the character looks to the right, the viewer naturally expects something to appear in that direction in the next shot.

Fast cuts create chaos and anxiety, while slow editing makes us focus on the details.

If a film shows a full-body shot of a character walking down a hallway, the scene might feel ordinary. But if we add a close-up of their tense face, then a shot of a hand reaching into a pocket, followed by a shadow behind them—the viewer is frozen in suspense.

How Are We Made to Feel Fear?

People are always afraid of the unknown. When a character hears footsteps behind them, slowly turns, and sees nothing, the viewer feels anxious. The human brain dislikes ambiguity and quickly fills in the blanks with the most terrifying possibilities.

Horror films skillfully exploit this trait of the human psyche.

Slow editing without music creates a feeling of time standing still.

A sudden jump cut—to the character’s terrified eyes or an empty space—disrupts our expectations.

Before a shocking plot twist, background sounds are often deliberately removed to intensify the impact.

The 1979 film Alien is a brilliant example of how cinema makes us fear something that barely appears on screen. The monster shows up only a few times, but the fear of its presence never lets go. That’s the power of editing—it raises more questions than it answers.

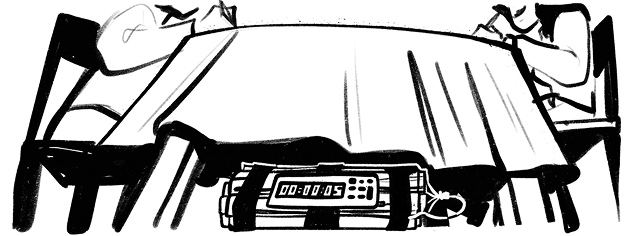

Suspense vs. Shock

Alfred Hitchcock explained the difference between these cinematic techniques like this: imagine people sitting at a table having a casual conversation, and suddenly a bomb explodes. Of course, the viewer feels shock—but it’s brief. However, if the viewer already knows there’s a ticking bomb under the table and watches the characters talk, unaware of the danger, the tension builds with every second. That is suspense—a technique that keeps the audience in prolonged tension and draws them deeper into the story.

Expectation vs. Reality

Comedy editing plays with rhythm and surprise, creating moments that make the viewer laugh. Jump cuts allow for abrupt scene changes that break logical continuity. For example, a character says, “I’ll never get drunk!” and the next shot shows them dancing on a table. The contrast between expectation and reality enhances the humor: a character jumps into a pool with pride, only for the next shot to show them standing in a shallow puddle.

Other key techniques for creating comedic moments include rhythm and timing. Long, awkward silences where a character realizes their mistake become funnier the longer the pause lasts. Rapid cutting, on the other hand, creates chaos: a character makes breakfast, sets the toaster on fire, spills milk, and ends up covered in flour. In comedy editing, timing is everything—a good editor knows when to let the audience absorb the joke and when to hit them with something unexpected.

Editing in Different Genres

In Documentary Films

Documentary editing is always an interpretation of reality. Cutting interviews, arranging facts, and even the length of pauses can shape the viewer’s perspective. You can show a politician confidently answering questions—or highlight their hesitations and awkward silences. The impact of the scenes will be completely different.

In the 2018 film Three Identical Strangers, editing plays a crucial role in revealing a shocking truth. At first, the film seems like a touching story of reunion, but as the pace and emphasis shift, it transforms into a dark investigation.

In Fictional Cinema

In fictional cinema, editing controls the viewer’s perception. Long, static shots create a sense of depth and reflection, as seen in Andrei Tarkovsky’s films, while fast-paced editing, in the style of Guy Ritchie, makes the scene dynamic and lively. Dramatic editing uses pauses: a character looks out the window, followed by a long silence, which is then broken by a sharp sound. In the 2000 film Requiem for a Dream, director Darren Aronofsky uses the technique of hip-hop editing, where rhythmic cuts—expanding pupils, a door slamming, the pressing of a syringe—intensify the tension and show the destructive effects of drugs.

Editing in Music Videos and Advertising

Editing in music videos and advertising follows the rhythm. Viral commercials often use ultra-fast cuts, where shots change at a breakneck speed, creating a sense of energy and drive. In music videos, synchronization is key: every drumbeat can be accompanied by a shot change, and smooth transitions between shots create a continuous flow. In the Weapon of Choice music video by Fatboy Slim, editing emphasizes Christopher Walken’s energetic dance, while in Take On Me by A-ha, the alternating between the real world and animation brings the story to life and makes it magical.

The Future of Editing and New Technologies

Currently, algorithms can automatically select the best shots by analyzing composition and rhythm. Programs based on neural networks can even assemble movie trailers on their own. In 2016, the trailer for Morgan was created by artificial intelligence, which, based on an analysis of horror scenes, edited a tense visual sequence.

In VR cinema, traditional editing nearly disappears. The viewer chooses where to look, and sharp cuts can disorient them. In such films, natural transitions are used: dimming, changes in lighting, or camera movements that gently shift the viewer to another scene. This changes the storytelling principles, making them more interactive.

Films like Black Mirror: Bandersnatch allow the viewer to choose the development of the plot. This requires a new approach to editing: scenes must form logical sequences regardless of the viewer’s choices. In the future, such technologies could lead to the emergence of “live” editing, where the video adapts to the viewer’s reactions in real time.

Editing evolves along with technology, but its main goal remains unchanged—to manage the attention and emotions of the viewer, creating captivating stories.

Editing: Frames into Story

“I love editing. I think I like it more than any other stage of making a film. If I wanted to be flippant, I would say that everything that happens before editing is just a way to create a film for editing.”

Stanley Kubrick

If the director is the author of the film, the editor is their storyteller. While the director creates the story, the editor determines how it will be told. The editor sets the emphasis, controls the rhythm, enhances emotions, and can even change the meaning of scenes. Good editing turns a great film into a masterpiece, while bad editing can ruin even the most brilliant concept. It is the editor who assembles the chaos of the filmed material into a cohesive, captivating story, making cinema what it is.

The atomic fortress has fallen. And our hair stands on end!

Thank you!