Literary ciphers: the hidden messages of writers

“To read and not to understand is the same as not to read at all.”

J. A. Comenius

To make the obvious hidden — that’s what the best minds of humanity have been doing for the past four thousand years. For practical purposes: cryptographers conceal information from prying eyes for the sake of security. For creative purposes: ciphers, cultivated in the field of creative practices, yield an endless harvest of new meanings.

“Business” cryptography is the domain of specialists. We gratefully use their work, staying away from the processes of creating strong ciphers and selecting the right key. “Creative” cryptography, on the other hand, involves all of us in mind games. Literature is especially rich in encrypted messages. Of course, we can turn to mediators — literary scholars — for interpretation. But there is a risk of receiving yet another layer of encryption if the key is chosen incorrectly.

A predictable thought flashes through the mind: “Let them teach me! I also want to understand at once what is written between the lines!” Excellent! That’s exactly what we were aiming for. The introductory lesson on unpacking literary meanings at the School of the Cipher is about to begin. We will learn by trial and error.

Ciphers Authors Play

Look, the profile of a teacher of literary encryption has mysteriously appeared on the school board:

— The topic of our lesson today is “Causative”.

— Oh, why such Tarabar?

— Glad to see you’re familiar with this term. But the veil of mystery over the lesson topic hasn’t lifted yet. In the 15th century, “Tarabar script” was indeed used as a system of secret writing. Cryptographers would arrange consonant letters in two rows and use substitute letters from the corresponding row when writing (vowels “did not participate” in the process).

Our topic is easier to decode. It’s an abbreviation of “The Secret Becomes Apparent!” This elementary encryption technique is well known to both our classical and contemporary authors. For example, behind the masks of pseudonym-abbreviations were hidden Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Anche), Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (A. P.). Of course, such transparent ciphers were not intended for secrecy. “The Sun of Russian Poetry” used the number code “1-14-17” (1 = A., 14 = the poet’s room number at the lyceum, 17 = P.). Pseudonym-abbreviations are more like a symbolic mark of uniqueness for a new creation, a sign of burning bridges between a newborn masterpiece and dusty old tomes. “I gave my surname to medicine,” A. Chekhov once explained the origin of his rich collection of several dozen unique pseudonyms, encoded in various ways. By the way, one of the most memorable masks the great classic tried on was the bold “speaking” signature “Schiller Shakespearevich Goethe.”

Not all abbreviations in the literary space are intuitively clear. For instance, the abbreviation-title of Viktor Pelevin’s collection of selected works, “DPP(NN),” easily leads potential readers into the dense thickets of possible interpretations or the dead end of hopeless “I give up!” Perhaps that was the intention. The author thoughtfully provided a decryption in the subtitle: “Dialectics of the Transitional Period from Nowhere to Nowhere.”

A guaranteed success awaits every novice decipherer of literary meanings when interpreting acrostics. In a manner accessible as an ABC book, this cipher is used by Konstantin Aksakov. The key lies “under the doormat” — in the title “Acrostic”:

My dreams and youthful strength

Only to you I have given, dedicating;

Soul with its wonders in bygone days

Continued stirring my childish heart!

Over the years I will remain with you,

With immortal beauty you shine.

The sum of the initial letters of the lines clearly highlights the meaningful unit (in this example — Moscow), which, according to the Author, should be considered key to understanding the poetic work. Aesthetic. Like a vertical neon sign you can’t pass by. Effective as a means of preventing thoughts from wandering aimlessly among intertwining rhymes.

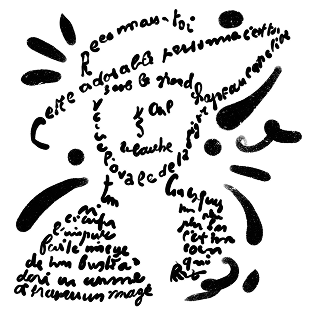

Another way of encrypting a poem’s theme (idea) based on the “key under the doormat” principle is calligrams.

The term itself belongs to the French avant-garde poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who arranged the lines of his poems in the form of drawings. The graphic code in his crypto-poetry was the very key to understanding the emotion that prompted the poet to pick up his pen. Crying streams of a fountain, an impenetrable wall of rain — these drawings allow readers to see in the text what hides within the shell of familiar words.

Immanuel Kant clearly defined the range of perception of one and the same object:

“One sees mud in a puddle, another — the reflection of stars.”

From one extreme to another wanders the thought of a person contemplating a real object. And in geometrical progression grows the number of interpretations for the one who dives into reading.

Read attentively, syllable by syllable, singing aloud: PU-DD-LE. Or like this: P – UDD – LLL.

Four letters are quite enough to launch your wild imagination into a long flight. Thanks to Apollinaire for his touching care for the reader. Illustrations act as portals to the author’s intention.

Anagrammatic coding is a more advanced level of literary ciphering.

The very process of hiding especially valuable information in the text looks like this: the cipher-creator shakes drops of paint from the brush of a key word, so that from the resulting splashes a curious mind could reconstruct the original meaning.

Deciphering implies gathering these letter-drops and arranging them in the correct linear sequence — up to the level of a single word, phrase, or sentence. A long gray beard trails behind this historical lifehack of writers. The first attempts to juggle letters in texts are found in ancient Eastern and classical literature.

The technique of encrypting individual words and entire messages by scattering “letter pollen” across literary material has survived to this day. And it feels great! It fits perfectly into selected authorial concepts. It is widely read and interpreted by clever readers. It is passionately criticized by critics: isn’t it self-deception to seek a cipher where nothing was encrypted in the first place?

As an example of using anagrammatic technique, appreciate the masterpiece of Dmitry Avaliani, a recognized guru of modern combinatorial poetry (a philosophical decryption for skeptics is provided by the Author himself):

Melancholia… Am I not a brute? (Russian: Melankholiya… Ne khamlo li ya?)

Games ciphers play with Readers

“Don’t jingle the keys to secrets,” — warned Polish poet and philosopher Stanisław Jerzy Lec.

When entering the artistic space of a work, remember that you are a guest. Don’t forget it! You may touch, but you must not break. The text has an Author — the host and the master (a visual poet in my place would have already inscribed this secret hint into a triangle — a Bermuda one, of course).

Respect the hierarchy. Deciphering a literary message does not mean producing a freshly squeezed remake in the end.

Let’s move on to the practical part. Let’s try to decipher the famous message for all puzzle lovers:

“Glokaya kuzdra shteko budlanula bokra and kurdyachit bokryonka.”

(A forest of hands raised!)

— An anagram, an anagram!!!

— ???

— A dragon growls. “Glokaya kuzdRA shteKO budlaNUla bokRA and kurdyaCHIT bokryonka.”

— Missed! The key to a non-existent mystery jangled too loudly. Professor Lev Vladimirovich Shcherba, author of this “educational” phrase, emphasized that none of these made-up roots mean anything at all. This extravagant set of words served as a model for studying the grammatical structure of language. But that’s already a completely different story.

— So, a mystery covered in darkness can turn out to be a hallucination?

— It can. And often does. Ciphers — or rather their phantoms — fool readers and even researchers. For instance, Richard Wallace at the end of the last century “figured out” Jack the Ripper. Finding non-existent anagrams in the works of Lewis Carroll, the self-proclaimed investigator reconstructed detailed descriptions of the murders. His letter games led to a “confession” Carroll had never made and had nothing to do with. Likewise, Professor Valery Chudinov claimed to have found “secret writings” in Pushkin’s own illustrations. The researcher managed to see exotic messages supposedly inscribed in microscopic letters along the lines of the poet’s many sketches. But these ghostly mysteries remained mysteries only in the eyes of the beholder. To those reading Pushkin, this “key” sounded far too loud.

— So, does this mean that any Author is so skilled in the art of ciphering that readers can never keep up, chasing after hidden meanings and running into dead ends?

— No need to overdo it! A book is for the reader, like a dessert is for the gourmet. At the same time, I will be glad if you leave my master class with the thought that great literature should not be read in one gulp “overnight” and not consumed as a dry concentrate of brief summaries.

Encrypted literary messages are often hidden in details. To pass by them without noticing is like swallowing a candy whole without biting into it and tasting the filling. Think for yourself, how would a chocolatier react to such a fleeting enjoyment of taste? With a pine nut or marzipan? It matters! The chocolate shell — the text — is not enough to penetrate into the author’s innermost thoughts.

The literary cipher is a very personal story, meant for a truly close reader. The author is ready to pour out their soul to anyone who takes the first step towards them, pulling that key out from under the doormat.

To the Reader, like to confession, came with her poems Anna Akhmatova. Only those who sought spiritual closeness could read the encrypted messages she left. The poetess was quite the huntress of men’s hearts. A stunning woman – she could afford it. In the “triangle” format, including the Bermuda one, of course, with the victims of broken hearts. One of her confessions looks like this:

Being silent in the morning is usual for me about

Overwhelming dreams I’ve seen.

Rosy roses, the beam and

I have sole fate.

Snow crawls from the sloping hills,

And I am whiter than snow,

Nevertheless, sweetly I dream of shores,

Rivers that are overflowing and muddy,

Every fresh noise of a spruce grove is

Purer than the dawn’s thoughts.

Who was the Silver Age Diva writing these verses about? From the poetic text as such, no photographic likeness emerges: no mustache, no blue eyes. The poem is dated 1916. Among the chronological “suspects”: Arthur Lurye, Boris Anrep, and Nikolai Gumilyov (her official husband, by the way). The list could go on. But is it necessary if the key has been found? The acrostic points to the perpetrator of this poetic celebration.

It is unknown how Anna Akhmatova would have encrypted a fellow literary colleague — Sasha Sokolov — in her poems. In any case, it would require quite a bit of imagination. The writer was quite skilled at encryption himself. And in a big way! Three years of studying at the Military Translators Institute did their job. His novel “School for Fools” is a real quest for deciphering hidden meanings. The boundaries of time (“non-existent time” — that’s the norm) and space (the Land of Kozodoy, the roof of the omnibus) are blurred. The main character-narrator sometimes splits into two, the storyline constantly breaks apart, never quite coming together. What filling lies hidden in this original textual candy? Where is the key? As usual, it’s at the entrance. In the title itself, which refers to a significant detail of the author’s biography: the young man was so out of place in the necessary frames that the question of placing him in a specialized institution was considered quite seriously. There’s also a “spare key” to the decryption. The book’s “father in an old pajama,” who will undoubtedly interest “Those Who Come,” strongly resembles the real father — the disgraced agent “Devi”, a world-renowned spy. To talk heart-to-heart, to reminisce — the autobiographical key is the guiding light in the dark kingdom of the novel’s meanings.

Is there a golden key to literary ciphers?

Let’s take note of the homework. We’ll get to know the right author a little better. Reading is a dialogue. You know that talking to strangers is dangerous. A small dive into biography and literary criticism will help you bring the mysterious author into the open. As a rule, a writer-cipherer, closing the door to the semantic space of their work, leaves the key in the lock. There’s no need to use a lockpick.

Has all great literature been “deciphered”? Yes, probably. That’s how it’s better preserved, staying relevant. Every decryption fuels interest in hidden meanings, adding layers of interpretation in the modern reading.

But you must know the measure. Don’t get too carried away, so to speak, with literary conspiracy theory, lest anagrams, numberonyms, and acrostics start to appear where the cipherer’s pen never ventured.

According to the Big Bang Theory, the Great Explosion of discoveries starts right now.

Thank you!