The evolution of food: From early humans to space cuisine

Dear readers, we have reached an era where a simple question like “What’s for dinner?” has turned into a real problem. And this problem is tackled with the help of experts: dieticians, nutritionists, and psychotherapists.

How did it happen that food became a source of meaning, manipulation, temptation, and sometimes even a weapon as humanity evolved? And what should we do: eat to live or live to eat? Where is the truth?

At first, we used to eat plants

For centuries, evolution meticulously refined the human brain and body chemistry. In those distant times, human living conditions were incredibly harsh: obtaining food required constant movement, but even that didn’t guarantee going to bed with a full stomach. Hunger was a driving force, a guide, and a constant companion of our species, and the mechanism of fat accumulation — a source of energy in uncertain situations —became the only means of survival.

Imagine for a moment an ancestor carefully or even with disgust setting aside a tempting piece of bacon on the edge of their plate. It gleams with fat so invitingly that it’s almost intuitive — this nutritious fat reserve will help them survive the winter and continue the lineage. Nowadays, we would gladly give that pink lump of fat to our dog, but back then, the very act of rejecting meat was equivalent to suicide.

Ancient people did not think about counting calories. There were no concepts like the right time for lunch or dinner, acceptable portion sizes, or food compatibility. They ate when they wanted, or more accurately, when they could. If they were lucky, they even ate twice at once! The world didn’t have abundance, let alone excess food!

So, our remotely ape-like ancestors gather around the campfire. But instead of the appetising chunks of meat we usually imagine, they enthusiastically devour bundles of leaves, roots, and ripe fruits. Instead of hunting wild beasts, they skilfully catch juicy insects to compensate for the lack of protein in their diet. They taste freshly picked bananas with surprise and then try to gnaw on tough roots to satisfy their hunger. We’re used to seeing textbook images of primitive people, just coming down from trees, running after mammoths with large sticks, but sticks and mammoths came later.

At the dawn of civilisation, ancient human ancestors were more gatherers than hunters. They skilfully moved through forests in search of edible plants and insects rather than chasing large predators.

Scientific studies suggest that tubers similar to modern potatoes were a primary food source for early humans. This finding prompts a new perspective on our distant vegetarian past. Some of our contemporaries, due to their plant-based preferences, have already returned to our ancestors’ roots.

In their historical past, humanoids synthesised vitamin C on their own, like most animals. However, as they later obtained sufficient amounts of this vitamin from fruits and plant foods, the need for its natural production diminished. Why produce it oneself if it could be easily acquired? Evolution…

And what about seafood? They were also of interest. Scientists believe that the skill of upright walking in humans evolved partly during the collection of shellfish for food. It turns out that we began enjoying seafood even before the appearance of Homo sapiens and haven’t been able to stop since.

Then we became humans

The harsh Late Proterozoic ice age was behind us. Food at that time was simple, coarse, and often raw. Our ancestors struggled to pick fruits from trees and hunted wild animals, then shivering from the cold, they would light a fire to roast juicy mammoth meat.

The cold and hunger literally drove primitive people to pick up a spear, kill a mammoth, wrap themselves in its hide, and prepare the first steak in history over an open flame.

Sitting by the roaring fire, our ancestors shared aromatic pieces of roasted meat, discussing how to divide the spoils and where to find more. Cooking allowed ancient hominins to spend less time chewing and digesting raw food, freeing up precious hours for developing communication and forming social life.

Complex cognitive needs required a more developed brain, which in turn needed more calories, and here cooked food came to the rescue.

One could say that it was the taming of fire and cooking that truly made us human. Perhaps it was then that the foundations of what we now call cuisine were laid.

Then we began to boil

Over time, people learned to domesticate livestock and cultivate grains and vegetables. New methods of food processing and preparation emerged — boiling, frying, and drying. This allowed for a more varied and nutritious diet.

Legumes, cucumbers, onions, and garlic were among the first foods to grace human tables. These nutritious and aromatic vegetables became stars of ancient cuisine and an essential source of protein. Our ancestors certainly did not suffer from a protein deficiency!

The first animals to be domesticated were goats and sheep, raised for their delicious meat and warm hides. Later, cattle were added, providing both meat and labor.

People began consuming milk 6,000 years after the start of animal husbandry.

In China and countries that adopted Chinese culture (Japan, Vietnam), the “milk” gene did not spread widely because the Chinese rejected animal milk on aesthetic grounds, considering it a form of excrement.

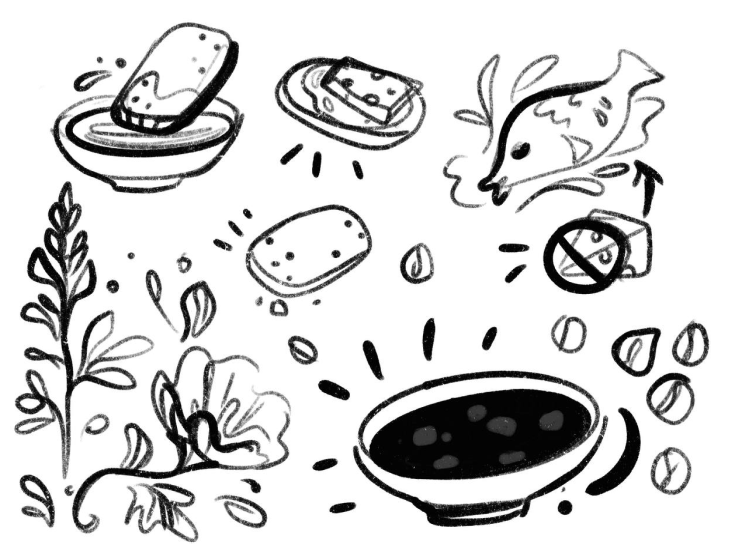

Archaeologists have determined that the first culinary masterpiece was a tasty lentil stew. Lentil stew was a major dish of the Ancient East, prepared in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Kingdom of Judah, but it is India that has preserved the love for this dish to this day.

Indian dal is made in a variety of ways, generously spiced with local seasonings (garam masala, dhania powder — ground coriander, mirchi powder — hot pepper, curry leaves, and dry mustard) and incorporating vegetables like tomatoes, unripe mango, and onions.

Nomadic tribes began exchanging products, knowledge, and recipes, leading to the emergence of the first national cuisines. From this point, people began experimenting with food.

Then we wanted a little more variety

Welcome to Ancient Greece, where bread is not just food but a whole cultural heritage! You find yourself in a distant era when fluffy yeast rolls were only a dream, and instead, you were greeted with humble yet nutritious barley flour cakes.

You eagerly enjoy this bread, first soaking it in aromatic wine (remember to dilute it, so you don’t become a barbarian!), and if you crave something sweet, spread some fragrant honey on your cake or top it with a slice of aromatic goat cheese. And of course, don’t forget to add a handful of juicy olives — there’s your breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

But don’t think that barley cakes were the worst option. Imagine how the poor Greeks had to make do with mallow flowers, lupins, or even grasshoppers!

If you could travel back in time and were served stale bread in Ancient Greece, don’t be too quick to complain. The Greeks believed that it had healing properties and could cure ailments. The treat should be accepted with gratitude, and refusing bread could invoke the wrath of the gods!

The first cookbook in the world was written by the Greek Archestratus in 330 BC. He was vehemently against baking cheese and fish together, believing it spoiled the dish’s flavor: baking should be limited to herbs and oil. To this day, people fiercely defend both this and the opposite viewpoint!

In Ancient Greece and Rome, grand feasts were a regular occurrence. Noble gentlemen would gather to enjoy delicious food, discuss philosophical questions, and even hold poetic contests — much like modern restaurants but with an ancient Greek flair.

A special place in ancient Greek cuisine was occupied by Spartan black broth. The mere thought of it terrified the residents of Greek cities. It consisted of pieces of pork floating in a thick, almost black liquid (pork blood), seasoned with vinegar and salt. That was the entire secret recipe for this dish. Sounds unappetising? Yet among the tough Spartans, this odd-looking, hearty, and nutritious soup was considered a true delicacy! It gave them the strength and endurance needed on the battlefield.

Julius Caesar’s legionaries carried bags of chickpeas with them. Here’s the first legume superfood in history. It’s amusing how they crunched on these chickpeas during the conquest of the Mediterranean. Surely, it gave them the vigour and energy for new feats.

Then, they thought about health

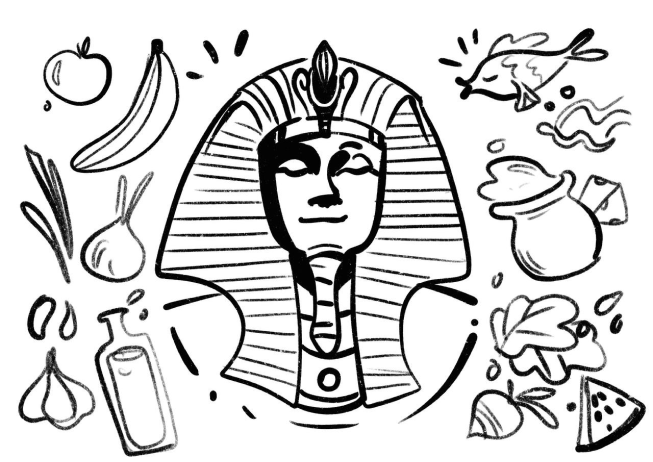

Despite their indulgence, Pharaohs adhered to a healthy diet and engaged in physical exercise, making them true advocates of a healthy lifestyle! They were the first to use the services of dieticians — this is why the average lifespan of a Pharaoh was higher, with many of them even reaching old age.

Of course, the Pharaohs’ diet was varied and included fruits, vegetables, onions, garlic, wine, and sea fish. Fried foods were eaten rarely, and salads dressed with olive oil were common. Milk and dairy products were also a staple. The Pharaohs avoided pork and river fish.

While rulers enjoyed a healthy and varied diet, the common people were the healthiest segment of the population: they ate little and moved a lot. Their diet consisted of fish, sour milk, lettuce, onions, cucumbers, radishes, apples, dates, olives, grapes, figs, melons, and watermelons. Meat and fresh milk were consumed rarely, as they were too expensive.

Unfortunately, not everyone in Ancient Egypt could boast of such a healthy lifestyle. Priests were unlucky — they had to consume all the rich sacrificial offerings. Their meals typically included pork, lard, butter, eggs, beer, and wine, leading to a range of health issues such as strokes, heart attacks, atherosclerosis, and diabetes. Most of them did not live past 30!

Ancient Pharaohs, as proponents of a healthy lifestyle, proved that proper nutrition and physical activity are the keys to longevity and prosperity!

Then we started eating again

Medieval cuisine is often considered primitive and unappetising. There were no culinary schools or Michelin guides in those times. However, “high” French cuisine did not arise from nothing. In the Middle Ages, people knew how to — and loved to — cook.

During this era, a meal was not just about eating; it was a true social statement: a festive feast was a measure of wealth and a common occurrence. If someone in the Middle Ages had wheat bread, wine, and meat for breakfast, they were considered part of the noble class. If they ate barley cakes, they were a simple peasant.

Cheeses available to peasants were not known for their softness; they had to be soaked and almost chopped with an axe. They were made this way for long-term storage. Real Parmesan is one such cheese.

But in medieval times, food was not only a matter of status; it was also medicine! Want to cure a fever? Try a barley infusion! And if you’re suffering from cholera, citrus fruits are the remedy. It was during this time that people began to understand that proper nutrition could not only prevent but also cure diseases.

Meat dishes in the Middle Ages were served with sophisticated sauces, which eventually evolved into delicacies like demi-glace, velouté, and sauce charon.

At a luxurious medieval feast of the upper class, true culinary exotica reigned: dolphin sausage, fish dessert, wine with milk. How about roasted “basilisk” or refreshing rooster ale? For entertainment, they might serve a chicken in knight’s armour sitting on a roasted piglet, or pies from which live birds flew out and frogs crawled. It was worth becoming a noble just for these gastronomic wonders! But not for long.

Nobles with weak hearts or stomachs could easily leave such a feast feet first. Gluttony among the aristocracy was common.

Bon appétit, friends!

We started fighting bacteria for food

About 200 years ago, science burst into our kitchens like a meteor in the night sky. Culinary scientists began working wonders with ingredients.

Researchers peered into the very heart of food, uncovering its secrets and laying the foundation for molecular gastronomy, where ordinary ingredients are transformed into true works of art.

Nicolas François Appert, the genius of Napoleon’s French army, invented a method of canning that allowed soldiers to enjoy fresh supplies even on the longest campaigns. Louis Pasteur discovered that milk and wine spoil due to ubiquitous bacteria.

These discoveries helped improve food quality and ensure the availability of products under various conditions.

Obesity and punishment

The history of fast food dates back to ancient times. Who would have thought that in ancient Rome people could grab a quick bite on the go, and in Russia there were their own analogs of modern fast foods?

When tired workers hurried home after a hard day’s work, they would gladly stop by street vendors (now it makes sense why they are called that) to quickly refuel with calorie-dense but satisfying food.

The globally renowned McDonald’s project is especially impressive — starting as a small family establishment, it evolved into a true global brand that influences the economies of entire countries.

However, this love for accessible on-the-go snacks has resulted in a real obesity epidemic. But, as often happens, one trend was followed by another — the rapid development of the healthy, conscious eating industry. Hamburgers were replaced by vegetarian dishes.

Thus, the 20th century, marked by the rise of American fast food, paradoxically also led to the emergence of a culture of mindful, healthy eating. It’s amusing to observe how trends follow one another, reflecting humanity’s eternal quest for balance between convenience and health.

Now we study science

Molecular gastronomy. Culinary madness where traditional dishes are transformed into true works of art: you slice a cup of coffee and then enjoy it with an airy mousse made from Borodinsky bread. Or you might try a salad that has turned into foam. How about caviar with an orange aroma or transparent dumplings?

Perhaps you’d like to cool off with crab ice cream? It sounds out of this world, but it’s the reality created by the mad geniuses of molecular gastronomy.

They turn familiar ingredients into genuine culinary puzzles, making our taste buds dance.

In 1988, in Oxford, two scientists, Hervé This and Nicholas Kurti, decided to look beneath the culinary veil and uncover the secrets of food preparation. They didn’t just study ingredient compositions; they dug deeper to understand why soufflés thicken and mayonnaise becomes dense.

Experiments showed that the physical and chemical properties of foods could be altered through special treatments. For example, if you cook an egg at 65°C for 90 minutes, the white becomes incredibly tender, and the yolk becomes elastic.

These discoveries laid the foundation for molecular gastronomy — a field that combines theoretical knowledge from chemistry, physics, and biology with specialised tools to alter the structure of ingredients and create unusual, captivating dishes.

And we study geography

Fasten your aprons, because now we’re diving into the fascinating world of national preferences.

Every people on our planet has its own signature dishes that stand out like stars in the sky. At the heart of these culinary masterpieces are two main factors: the range of raw ingredients and the methods of processing them. Nature, agriculture, and fishing provide the ingredients. The country’s geographical location, climate, and economic conditions directly influence which products are used in its national cuisine.

Countries near seas and oceans delight in dishes made from fish and seafood. In forest-steppe regions, livestock products and forest treasures are more common. Southern peoples adore vegetables and fruits.

In China, they are obsessed with salt, using it in almost everything. They even manage to salt fruits! And vegetables? There are so many that you could have an entire vegetable parade. Grains, legumes, and fruits form the core of the diet for these food enthusiasts. Meat? Who thinks of it when there is such a variety of delicacies!

Interestingly, the Chinese do not believe in overheating. They think that the less cooking, the more beneficial the food is, so most dishes are prepared by steaming or are served raw. If you want something hotter, you can always add a pinch of chilli pepper!

The Spanish siesta helps restore energy, normalise blood pressure, stimulate brain activity, and compensate for possible nighttime rest deficiencies, which often lead to weight gain. Another healthy habit of the Spanish is frying and stewing foods in a dry pan (without oil) and choosing local, natural products.

The Japanese diet is a true treasure of health: vegetables, grains, fish, and seafood. Most dishes are cooked without oil, by boiling or steaming. Not a gram of excess fat! But the most interesting aspect is portion size. Instead of large plates, the Japanese prefer many small cups and bowls, from which each person takes only a little. They leave the table slightly hungry.

People in hot countries love spices and hot sauces, while those in colder regions prefer milder flavours. Climate also influences the dishes themselves. Hot countries have cold soups, while cold countries have hearty and fatty dishes. Take, for example, Spanish gazpacho or the calorie-rich dishes of Central Asian peoples. All to either warm up or cool down.

In nomadic cultures, there is a predominance of fermented dairy products and dried meat.

In frosty Scandinavia, locals know exactly how to stay warm in the harsh climate. Their cuisine is rich in hearty and nutritious dishes that provide energy for the entire day. In Switzerland, there is a special preference for sea fish — a true treasure trove of beneficial fatty acids. And, of course, the Swiss do not go without rye bread, which, unlike white bread, is much better for the figure.

Indian cuisine: vibrant, aromatic, spicy, magical, and extraordinary. The dishes explode with flavours thanks to spices. Curry is the hallmark of Indian recipes. Spicy seasonings not only enhance aroma and taste but also help combat possible digestive disorders. Locals don’t know what high cholesterol is.

Mexicans know exactly how to avoid overeating while still feeling full until evening. Their traditional “almuerzo” is a true meal monster that energises you for the entire day. It saves you from hunger pangs, snacks, and allows you to enjoy a delicious and satisfying meal in the middle of the day.

Central Asia entices with its unique cuisine. When the thermometer soars above 40 degrees Celsius, locals don’t rush to clear plates of heavy, calorie-laden dishes. Instead, they wisely wait for the sun to set. As the evening coolness wraps around the earth, juicy meat dishes appear on tables, capable of energising even the most exhausted traveler. In these regions, there is a sharply continental climate: daytime heat and a significant drop in temperature in the evening — one needs to replenish the energy spent during the day.

Every national cuisine is a story told through food. Each dish reflects the natural wealth, climate, and traditions of its people.

To revolutionise food

The 19th-century Industrial Revolution fundamentally changed the ways food was produced, stored, and delivered, making it more accessible to the general population.

The SPACE10 laboratory is clearly not afraid to experiment and bring bold ideas to the future of food: creating meatballs from artificial meat, food waste, algae, powders, and even insects represents a truly creative and innovative approach. And hot dogs with carrot-beet sausages in a spirulina bun, root vegetable burgers with mealworms, and microgreen ice cream are already out of this world! It seems that the future of food will increasingly depend on technology.

Unusual products might surprise and even shock us, but if they prove to be tasty, nutritious, and healthy, in time, we might gladly eat celery burgers or parsley ice cream.

We live in an era of unprecedented diversity and availability of food from around the world. We can enjoy exotic dishes and experiment with new flavours and combinations. Scientists are already proposing revolutionary solutions: from algae embedded under the skin to 3D food printers that could be used even on space missions.

Perhaps the day will come when we simply step out into the sun to “recharge” with nutrients like a battery? The evolution of food continues, and who knows what surprises it will bring us next!

According to the Big Bang Theory, the Great Explosion of discoveries starts right now.

Thank you!