Ode to food: A journey through the kitchen with curious mice

Disclaimer. The editors of The Global Technology magazine insist that the article is for informational purposes only and strongly advise against looking for similarities between fictional and real-life characters.

What could be more serious than a popular science publication and what could be more serious than food? This time, the editorial office of The Global Technology magazine decided not to joke and wrote a serious essay with serious chapters, where they spoke about several products in all seriousness. You as well need to read the article seriously, occasionally interrupting for non-serious activities.

A serious beginning

“Get into this hole already, look at you, you’ve gotten fat,’” said a little grey girl mouse, pushing her friend into the crevice of a residential building. The friend of the tiny playful mouse was a mouse with a torn-off tail who was much larger than his friend. His head fit perfectly into the crevice, but his round, fluffy body just wouldn’t go any further.

“I haven’t gotten fat, I’m just scared,” the little mouse squeaked quietly, realising that he was hopelessly stuck.

“We need to get to this kitchen,” the girl mouse objected and began to fuss. She pressed her little hind legs into the ground and leaned her back against the withers of her companion, trying to push him deeper into the crevice. The little mouse desperately resisted, realising that he was losing his already meagre fur.

Then the little mouse climbed onto her friend’s back and began to jump along it, thinking that that way her fluffy friend would get through the tight crack faster. But this neither led to anything, and the remains of the mouse’s fur began to fly with such incredible force that for a second the girl mouse thought it was snowing.

She wearily sank to the ground and sighed: she shouldn’t have chosen this tailless creature as her companion. But the culinary paradise was so close! The owners of the house were not there, and the crack at the bottom of the slightly rotten foundation seemed to be deliberately inviting uninvited guests to come into the house. How could you miss such an opportunity!

The mouse turned her tiny nose in the direction of the wind — the sweet smells coming from the kitchen were driving her crazy. She imagined how she would carefully step onto the parquet, how she would lick up all the milk spilled from the refrigerator onto the floor and not leave a drop! How she would carefully sneak into the refrigerator, how she would gnaw holes in all the products with her sharp teeth, how she would find a box of apples in the basement, and how she would then bite into each apple up to her mouse ears.. Oh!!!! She would simply become a Princess in this kitchen!!

But the round body of the mouse’s friend with a torn off tail, which treacherously wouldn’t fit into the crack of the house, brought the mouse back to reality. She once again ran around the heavy body of her friend, released her tiny claws and began to tickle him.

“Stop it! Stop it! What are you doing!” the mouse squealed desperately. “Stop it, I’ll start sneezing! A-a-a-a-a-a-a-hchoo!”

Before the girl mouse had time to come to her senses, her little friend, like a fast bullet, slipped into the crack, rolled across the wax-rubbed parquet floor of the kitchen and landed head-on in the bottom drawer of the chest of drawers, from which, as if on cue, nuts began to fall with a crash.

She jumped up in surprise and ran into the crack after the little mouse.

Chapter 2

The Source of Optimism — Greek Cereal

“Where am I?” the little mouse asked the girl mouse, sitting on a pile of nuts.

The girl mouse crawled up the nut pile and touched her friend’s forehead with her tiny paw. Right on the top of his head a pink bump was pulsating furiously.

“People call this place the kitchen. Here they store different products using which they prepare their food. Can you see the colourful jars on the shelves?” the girl mouse pointed upwards with her head, “These are seasonings. And there in the corner is a rattling refrigerator, where people put their food in the hope that it will not spoil, and that we will not get to it.”

She waved her tail and ran down to the floor from the nut pile.

“Come here!” she beckoned to her friend with her tiny paw. “I’ve found something for us to gnaw on now.”

The girl mouse deftly climbed onto the smooth surface of the tabletop, from which she gracefully jumped onto the cutting table, from which she quickly climbed into the kitchen cupboard, where some boxes were standing.

“Here it is!” she said with a smile and crunched something loudly.

The little mouse did not want to climb so high at all, he did not want to go on this adventure either. He never understood why the world was arranged completely differently from how he would like it: why they — mice, are often disliked, why they are put in all sorts of obstacles in the form of terrible mousetraps and not very clean cats, and, finally, why mice always have to get their own food. Can’t food itself find mice? A monstrous injustice pushed him into this ill-fated crevice and as a result — he is sitting with a huge bump on his head on a pile of nuts and is forced to crawl somewhere again.

The little mouse remembered how he loved lying in his hole under a tree and slowly reflecting on the hardships of a mouse’s life, but the loud crunch of his friend awakened the last of his strength and he tiredly climbed up the leg of the kitchen table towards the top drawers.

There really were some boxes in the kitchen cupboard at the top. The little mouse knocked on the cardboard side of one of them and read:

“Greek cereal. Hmm… the owners of this kitchen are either inveterate travellers or inveterate ignoramuses. Why bring cereal from Greece?”

“Come on, eat it,” the girl mouse commanded, handing the little mouse a few brown grains. “Greek groats, Greek noodles and buckwheat flour do not necessarily have to be brought from Greece. But no one knows why the Greek groats from which all this is made are called Greek. Maybe because they were brought from Byzantium, maybe because the Greeks cultivated them in monasteries. Discussions about what exactly was called ‘Saracen grain’ — buckwheat or rice — are based on a misunderstanding. In some sources, ‘Saracen gra’ is rice, and in French and Italian — it is buckwheat. Actually, many grain crops penetrated Europe from the East, and all of them are in some sense Saracen and infidel.

The girl mouse watched as the lazy little mouse leaned back against the kitchen cabinet door, and, forgetting about his abrasions, was diligently gobbling up the cereal.

“Oh, I wish I had your carefree attitude,” she drawled, shaking off the root shavings. “They write a lot these days about new, exotic, or undeservedly forgotten sources of nutrients. For example, have you heard of horse beans, or Russian beans — the very ones our ancestors lived on in a difficult economic situation, until green beans came into fashion? Or about the oil-rich babassu palm from the Amazon forests, which the natives call the ‘cow plant’? Experts say that insects are also quite good if fried, after all we need to get food for the eight billion mice and people on Earth somewhere… However, we don’t want arthropod larvae yet, but, say, some American experts even include buckwheat in the lists of promising traditional crops”.

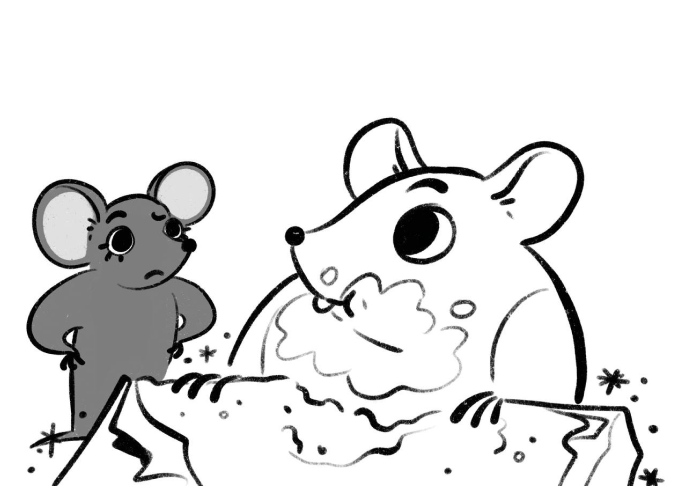

“Cultures,” the little mouse repeated after his friend, licking his paws. “I’ve really put on weight lately. Buckwheat will definitely add a couple of extra kilos to me.”

”It won’t,” the girl mouse answered. “For porridge, it’s low-calorie — 110 kcal per 100 g, you can’t expect less from a product rich in carbohydrates. For comparison: rice porridge has 144 kcal per 100 g, white bread has 200-300.

Buckwheat is recommended for diabetes — it is proven to prevent the increase in blood sugar levels, and also to reduce the level of ‘bad’ cholesterol. And also, you are now chewing a lot of iron, magnesium, copper, manganese and phosphorus, and all these mineral components are well absorbed, because buckwheat is poor in phytic acid, which reduces their bioavailability in many cereals. And buckwheat is rich in antioxidants and vitamins.”

The little mouse looked in surprise at the girl mouse, who was already ready for new adventures, and frowned his brown nose:

“You can’t eat much of this buckwheat! It smells!” he said tragically.

“Yes, it smells,” said the girl mouse, thinking about how to open the refrigerator. “This is not pasta. The main component of the aroma of buckwheat is often called salicylaldehyde, but others are also important. Different shades of smell are formed with different cooking modes, but this issue is still waiting for its study. Maybe you will study it? What do you say, Tailless? Let’s take some more of these wonderful kernels with us and make buckwheat flour out of them. But we will definitely have to add regular wheat flour to it, otherwise everything we decide to cook together will fall apart, because buckwheat does not contain gluten.

At these words, the girl mouse straightened up and took the box of buckwheat from the tenacious paws of her friend. The little mouse, having lost his balance along with the box, staggered and with a cry “Help!” quickly flew to the floor.

Chapter 3

Ice Cream Between Life and Death

During the flight from the cutting table, the careless little mouse hit the freezer door, from which a block of ice cream fell out onto the floor. The block landed in the corner of the kitchen, and the little mouse glided on top of it.

“It’s so cold!” he squeaked, jumping from paw to paw, “Can I eat this ice too?”

“Oh, my God, you’re so clumsy,” the girl mouse concluded, smoothly descending along the long curtain onto the block of ice cream. “Although in the name of gluttony, cooks were also ready for anything — even for scientific discoveries.”

The mouse pulled the edge of the block with its sharp teeth, which immediately formed a hole, from which a small piece of cold white mass fell out onto the little mouse. The little mouse immediately started licking the ice cream off himself and got so carried away that he didn’t notice how he had buried his head in the cold block.

“Where are you going again?” the girl mouse asked discontentedly. “What’s with the habit of starting to eat right away without even knowing what you’re eating?”

“And what?” the little mouse showed his head from the block. “It’s delicious and that’s enough.”

“It’s delicious,” the mouse mimicked the little mouse, breaking off a small ball of ice cream. “By the way, you’re currently eating one of the most complex dishes in the world from a physics point of view.”

The little mouse didn’t know what physics was, but in anticipation of an interesting story he crawled out of the block.

“According to a legend, the English King Charles I once decided to show off in front of his guests and threw an unprecedented banquet,” the girl mouse began, wiping the remains of the ice cream off the little mouse. “The dinner was a great success, but the chef saved the most interesting thing for dessert. The dessert resembled a mysterious dish, according to eyewitnesses, it looked like freshly fallen snow, but at the same time it was tender and sweeter than anything known to English aristocrats at that time. Charles called the chef and ordered him never, under any circumstances, to share the recipe for the outlandish dessert with anyone — the king wanted it to remain the signature feature of the English court. Fortunately, when Charles I was beheaded in 1649, his chef did not overdo his loyalty to his employer, otherwise we might have been left without ice cream forever.”

The mouse sighed, the prospect of being left without the delicacy that he had just tried seemed very sad to him. He carefully approached his friend and asked:

“And what does physics have to do with it?”

The mouse perked up and looked closely at the little mouse:

“There are still disputes about who, when and in what form invented frozen desserts. It is known that the Roman emperors used to enjoy sweetened ice. Similar recipes are even mentioned in the Bible!” the mouse raised her voice. “But ice cream in the modern sense is a much more complex product than ice with sugar. Ice cream is practically a special state of matter.”

The little mouse realised that he did not know what matter was, but the thought of seeming stupid kept him from asking: “Why?” Fortunately, the mouse decided to explain everything herself, and after dipping her paw into the briquette, she began to quickly draw something on the parquet.

“If you just freeze cream, it will be hard as a rock. Right?” she asked the little mouse. He nodded in agreement. “ But this problem can be solved with the help of sugar — it lowers the melting point. Simply frozen cream melts at almost 0 °C like water. By adding sugar, this temperature can be lowered to –18 °C, which is slightly higher than the temperature of a regular freezer.

The little mouse froze, watching as the girl mouse continued to write unseen formulas.

“What happens as a result? Let’s say we took a jar of ice cream out of the freezer. At this point, its temperature is about –20 °C. Within a minute, the solid ice cream warms up to a critical –18 °C and begins to melt.”

The little mouse glanced out of the corner of his eye at the puddle of ice cream spreading across the floor.

“If you take a whole reservoir of very cold ice and put a pan of cream in it, you won’t be able to freeze the cream, because the ice warms up to 0 °C very quickly, literally in a few minutes. At this point its temperature — and, consequently, the temperature of the cream — stops changing until all the ice melts. But to freeze sweet cream, as we have established,” the mouse ran to the beginning of her manuscripts on the floor, “lower temperatures than 0 °C are needed. Therefore, in the old days, they used the same trick as in ice cream itself: the melting point of ice was lowered by adding a foreign substance. But — not sugar, they used salt. They took a trough of crushed ice and generously sprinkled it with table salt. As a result, the ice began to melt faster than “unsalted”: specifically at the same –18 °C. But this temperature was maintained for several hours, because the temperature does not change during melting. As a result, an improvised freezer on “salted ice” was obtained. You could put a bucket of sweet cream in it and after about half a day of diligent stirring get the desired product — ice cream.

The little mouse finally lost the thread of the conversation, but still did not interrupt the girl mouse. She stood up on her hind legs and continued in the lecturer’s voice:

“The most important thing is that the temperature does not change during melting. All the heat absorbed by the ice cream is spent on breaking the water crystals contained in the ice cream into individual molecules of liquid. This property of the melting process — temperature stabilisation — gives us a few minutes to enjoy the ice cream as intended. By the way, for the same reason, drinks are cooled with ice, and not with cold stones, as some manufacturers of whiskey accessories suggest. The essence of ice is not just that it is cold, but that it melts — and thus maintains a constant temperature of the drink.”

The mouse sat down. He had never seen his mouse friend in such an excited state.

“You understand, Tailless,” the girl mouse babbled in mouse language, “Ice cream is a dish caught between two states of matter: solid and liquid. Roughly speaking, what is in the bracket is a mixture of a bunch of molecules that do not want to mix. We love it for the melting process — this is the only way to get a dessert that is both icy and soft.”

The girl mouse looked tiredly at her notes.

“What can I say… ice cream is a culinary metaphor for an internal struggle.”

The little mouse saw that his friend was thinking. He really wanted to somehow cheer up the girl mouse, so that they could continue such a wonderful culinary, albeit not entirely legal, evening.

Chapter 4

The Bitterness of Coffee Grounds

The little mouse wandered around the parquet, looked into a socket located near the sink, which was jumping out of its nest, ran along the hood and saw a huge, puffing plastic unit. The unit stood on the windowsill, had 2 containers and was making gurgling sounds. Periodically, some dark liquid poured out of the upper container into the lower container.

The little mouse walked around the lower glass container and met the girl mouse there.

“Congratulations, Buddy!” the girl mouse smiled, “you found coffee.”

“Buuuut… but we are not going to eat it, right?” the little mouse asked hopefully, crawling away from the coffee machine.

“Coffee is not eaten,” the girl mouse concluded. “It is drunk. People drink it when they want to perk up. And the state of vivacity from coffee in people occurs because coffee contains an alkaloid — caffeine. Caffeine binds to adenosine receptors of brain cells instead of adenosine itself, which normally causes sleep and suppresses excitement.”

The little mouse, trying to come to his senses from a new portion of information, shook his head.

“I think I’ve just remembered,” he said happily. “My relative, who was the main field mouse, told me a story about how coffee was discovered by an Ethiopian shepherd. He noticed that goats, having eaten leaves from a coffee tree, stay awake all night long, and then play pranks, just like us.”

The little mouse began to dance, and the girl mouse began to dance after him.

“It’s strange that the goats didn’t find tastier leaves for themselves,” said the girl mouse, going into another step. “Caffeine tastes bitter, like many alkaloids, but it is not it that creates coffee bitterness. One of the most famous components of coffee beans is chlorogenic acid (it does not contain chlorine, the name is translated from Greek as “generating greenery” — it turns green when oxidised). When roasted, it partially decomposes into quinic and coffee acids, and also forms lactones — they are what make medium-roasted coffee beans bitter.”

The little mouse stopped and touched the coffee machine with his paws.

“So I didn’t get it: is coffee bitter or not? Can I drink it or not?”

The girl mouse also decided to take a break from the fiery dances and give the little mouse the answer:

“Some connoisseurs believe that properly brewed coffee should not be bitter, although this statement is controversial. All these scientific discussions about the benefits and harms of coffee probably began with the ‘coffee experiment’ of King Gustav III of Sweden at the end of the 18th century. Being worried about his subjects who had become addicted to the new-fangled drink despite the ban, the king granted life to two identical twins sentenced to death, so that one of them would drink three cups of coffee every day, and the other one — three cups of tea. The one who drank tea died first, at the age of 83. The date of death of the second one is unknown.”

The little mouse looked at the girl mouse with delight. After their tasty adventure, he decided to find out at all costs how such a tiny head could contain an entire encyclopedia. Or maybe he would be able to surprise his friend with a culinary recipe, and then…

The little mouse’s thoughts were interrupted by the voice of his friend:

“Tailless, come here! Come help me, quickly.”

The little mouse saw that his miniature friend had climbed down the refrigerator coil, hooked one of her back paws onto the door handle and was desperately gnawing on the seal. The little mouse immediately joined in and began to gnaw on the seal on the other side. The refrigerator door creaked and slowly opened.

“Please,” the girl mouse said, jumping onto the bottom shelf of the refrigerator.

“With pleasure,” the little mouse answered in a voice full of delight.

Chapter 5

Eggs of Destiny

“Well, well, well” the girl mouse began in a businesslike tone, “Let’s take a look around. What do we have here? Aha, chicken eggs.”

“Did I hear it right, chicken eggs?” the little mouse asked in surprise, approaching the refrigerator door. “Do people really eat female reproductive cells of another species on a massive scale? And I was wondering why they love mouse traps so much…”

“Well, for a biologist, a bird’s egg is really a giant egg cell in a special package, maturing outside the mother’s body. That’s why it’s so nutritious. And people really do eat it.”

The little mouse jumped right into the box of eggs, causing one egg to crack.

“And what have you done?” the girl mouse asked in the voice of a strict teacher.

“A discovery,” the little mouse spread his paws, “Water is leaking from the egg.”

“Not water, but an egg white,” said the mouse, trying to attach the shell back. “In 1800, the chemist and Minister of Education of Napoleonic France Antoine de Fourcroy described special substances that under the influence of acids or high temperatures coagulate in a characteristic way and are contained, for example, in eggs or human blood. De Fourcroy called them albuminoids — from the Latin albus ovi, literally ‘egg white’. This is where the name ‘egg white’ and the German ‘Eiweiss’ come from. And the international — protein was proposed by Jens Berzelius only in 1838. An egg in a frying pan does not spread in a thin layer, like water, thanks to the glycoprotein ovomucin — there is 2-3% of it in raw egg white, but it is ovomucin that makes it gel-like. Since the egg white is viscous, it can be whipped into a stiff foam. If you add sugar, you’ll get meringue, if you add salt, it’s an omelet component. By the way, ovomucoid is the main allergen in chicken eggs and a favourite target of the immune system.”

The little mouse looked at the sticky water that continued to flow out of the hole in the egg shell. The mouse decided to stop it with his strong tiny paws, but only made it worse, the hole in the shell got bigger and something yellow appeared from it, very similar to the sun.

“There’s something else in the egg besides water,” he shouted.

“You’re so clumsy,” the girl mouse shook her head. “Of course, in an egg, in addition to the protein, there’s also a yolk. There are proteins in it too, but there is even more fat. It is made yellow by lutein and zea-xanthine, which are carotenoids — relatives of vitamin A. Yes, the yolk contains cholesterol, but besides it — many vitamins: A, D, E, K, vitamins of group B. So all these natural masks for hair and skin containing raw yolks are a good thing, and eating eggs is more useful than harmful, if you keep to moderation.”

“But everywhere it is round yellow, and in this egg it is orange,” the little mouse did not calm down.

“This is because the chicken ate some bright flower while walking. Or the manufacturers added natural extracts of carotenoids to the chicken feed, for example, from calendula petals. If you feed chickens extracts of pepper colouring substances, you can get eggs with red yolks, although, probably, red yolks are not a very good idea.”

“Then why does this egg smell bad?” asked the little mouse, pointing to an egg lying to the side. “Did the chicken eat something wrong again?”

“The specific ‘egg’ smell is formed by the same substance that causes the smell of rotten eggs — hydrogen sulphide. There are always sulphide groups in egg whites, and the more sulphide is released during cooking or excessively long storage, the stronger the aroma is. By the way, the greyish coating on the surface of the yolk in an egg that has been boiled for too long is iron sulphide. It is formed from the iron contained in the yolk and hydrogen sulphide in the egg white. It is not pretty, but it is not harmful to health.”

The girl mouse interrupted her story, noticing how her companion opened his mouth wide to try to swallow the egg whole, but instead got stuck in the egg carton.

“The shell consists of calcium carbonate crystals immersed in a protein matrix,” said the girl mouse, freeing her little friend from the egg captivity. “The smallest pores in it allow the egg to ‘breathe’. An interesting detail: a boiled egg, which has been stored for a long time, is easier to peel than an egg from fresh stocks, because during storage, carbon dioxide evaporates from it and the internal environment becomes more alkaline. And in an alkaline environment, egg whites interact less strongly with the shell. The brownish shell is coloured with the pigment protoporphyrin. When processing the egg, a classic example of protein denaturation occurs: neat globule balls unwind, threads get tangled and form a tight network. Therefore, if you overcook the eggs in a frying pan, the scrambled eggs will be like a shoe sole.”

The little mouse looked at his friend with gratitude; he did not want to lose the remains of his tail, just as he did not want to eat the shoe sole. He climbed up the shelf in the refrigerator and saw round jars with the word ‘Mayonnaise’ written on them.

Chapter 6

Forbidden Mayonnaise

“Mayonnaise… what a word,” he said, puzzled. “Mayonnaise… people do like to complicate things!”

The girl mouse turned toward the round jars with the light substance and said enthusiastically:

“The name is certainly not simple, but neither is the product. People call mayonnaise the sauce of love and hate.”

“I’ll taste this human hatred,” the little mouse squeaked conspiratorially.

He deftly hooked the lid with his paws and began to turn it like bus drivers turn the steering wheel. The lid gave in, and the mouse happily began to taste the mayonnaise that remained on the walls of the lid.

“An emulsion of oil in water, ugh-h-h! I’ll never put it in my mouth again!” he backed away discontentedly.

“Structurally, the sauce is similar to a dairy product, but chemically — not so much,” the girl mouse answered, climbing into the lid.

“How do you even cook it?” asked the little mouse, sniffing the lid. “Do they take one yolk, a spoonful of water and an acid solution, a cup of oil — and get an emulsion of oil in water? Not the other way around?”

“That’s the very trick — not to make it the other way around. The water solution in the mayonnaise should become a continuous phase enveloping small balls of oil. It is this unusual structure that makes the mayonnaise thick. It’s paradoxical, but true: the thickness increases when oil is added, not yolk.”

The little mouse climbed out of the lid and looked around: there was a lot of mayonnaise in the refrigerator.

“To achieve the desired result, the mayonnaise is mixed twice: first, they mix everything except the oil, then they pour in the oil in a thin stream, not exceeding the dosage and stir the mixture very, very vigorously. The spectacle is amazing: two transparent liquids create a creamy sauce, and it’s so thick that the spoon stands up straight!” The mouse closed her eyes, imagining how she was mixing mayonnaise. “The mixture is made stable by the lecithin emulsifiers contained in the egg yolk. And all because the lecithin molecule is bipolar, one end of it is hydrophilic and loves water, and the other is hydrophobic, also known as lipophilic, and loves oil. By separating the two liquids, the lecithin layer helps them reconcile with each other. To increase the likelihood of success in making homemade mayonnaise, some recommend adding a little ready-made fresh mayonnaise or a pinch of xanthan gum to the mixture before pouring in the oil.”

“And all this is just for this?” the little mouse ruffled his fur in displeasure.

“Yeah,” the girl mouse confirmed. “As Italian scientists have established, mayonnaise made from super-healthy extra virgin olive oil is more liquid than mayonnaise made from refined olive, sunflower or peanut oil, with larger droplets of oil. (Carla Di Mattia et al. // LWT — Food Science and Technology. 2014) And about the sad part: homemade mayonnaise, with all its advantages, is made from raw eggs, hence the risks are obvious. In any case, the shelf life of homemade mayonnaise is up to a week in the refrigerator, better less.

“Who needs this mayonnaise?” thought the little mouse and began to climb up the shelf.

Chapter 7

Ambiguous Meat Jelly

There he saw something that he had never expected to encounter on a secret culinary walk. The little mouse’s delight knew no bounds, because in the refrigerator he saw a real trampoline.

He immediately began to jump on it.

“Come here!” he shouted loudly to the girl mouse. “What fun!”

His friend instantly appeared on the top. Who could believe it — a trampoline in the refrigerator! However, the little mouse was really jumping on something very springy, turning over in the air and flying between a saucepan of soup.

The girl mouse looked at the trampoline with disbelief.

“Hmm…” she squeaked. “But this is real meat jelly! You can rarely find such a delicacy in the refrigerator, those who live here must not come from here.”

“Meat jelly”, the little mouse cried out enthusiastically, flying up again. “Now it’s my favourite food!”

“You haven’t even tried it yet,” the girl mouse said, trying to calm the little mouse’s ardor. “The main thing in meat jelly is not meat at all, the main thing in it is collagen. The obligatory components of jellied meat are legs and ears, tails, pieces of skin and pork legs. In a word, everything that contains collagen.”

“And what about meat?”

“And too much meat in jellied meat can harm it, the jellied meat simply won’t harden.”

“Is collagen edible too?” the little mouse didn’t stop.

The word “collagen” can be translated from Greek as “the one who creates glue.” Collagen is a protein of connective tissue: bones, cartilage, tendons, skin, in short, one of the main materials of the mammal’s body. The molecules of this protein are long thin spirals, twisted in threes to form a thicker spiral, larger fibrils are assembled from the triple threads, and even larger fibres are assembled from those. The collagen threads are connected to each other not only by hydrogen bonds, but also by covalent bonds, so the resulting fabric is very strong — you won’t be able to chew it right away. And with prolonged heat treatment, collagen hydrolyses, and both hydrogen and covalent bonds are broken. Therefore, the jellied meat has to be cooked for a long, very long time.”

“Wow!” the little mouse said, turning in the air. It seems that he really decided to learn all the secrets of cooking this rare dish. “Does collagen really make the jellied meat springy like a trampoline?”

“After we have disassembled and chopped the meat, laid it out on trays and poured hot broth over it, we add gelatine there and it begins to harden. The protein molecules again form hydrogen bonds, enter into hydrophobic interactions, and in places twist into triple helices, like in collagen. A molecular network is formed and it holds water, thus jelly appears,” the girl mouse answered, joining her friend.

“I know, I know,” the delighted little mouse cried out. “Gelatine is used to make capsules for tablets, paintball shells, and muscle dummies for ballistic examination!”

Chapter 8

Talking Mushrooms

The mouse enjoyed jumping on the jellied meat so much that he wanted to jump higher and higher each time. Making another jump, he deftly turned over in the air and caught an unseen vegetable in the shape of an umbrella with a thick handle with his paw. The unknown vegetable softened the mouse’s landing on the hard shelf of the refrigerator, but the mouse still hit it painfully with his round body.

“Oh,” he whispered, rubbing his side with his paw. “What is this?”

“I don’t know,” the girl mouse answered, sniffing the unfamiliar product.

“It’s neither an animal nor a plant,” the little mouse concluded thoughtfully.

“Although, probably it once grew in the ground,” the girl mouse supported her friend.

“I think I have seen something like that in the cartoon Ratatouille. There was a scene where the ceiling collapsed on the mouse while he was holding something in his hands. At first, I thought it was an umbrella,” the mouse squeaked.

“Tailless, you’re a genius!” the girl mouse exclaimed. “It’s not an umbrella, it’s a mushroom!”

The mouse smiled happily upon hearing the praise and eagerly awaited the next story from his resourceful friend.

“On the one hand, mushrooms are plants, but as soon as you start to analyse their chemical composition, inconsistencies begin,” the mouse once again tried on her favourite role of teacher. “Mushrooms store carbohydrates not in the form of starch, like all normal plants, but in the form of glycogen, just like us and people. At the same time, the mushroom cells have a hard wall, which distinguishes it from us and seems to bring it closer to plants. But this cell wall contains chitin and chitosan, substances that are usually found in the shells of insects and other arthropods. The end product of nitrogen metabolism in fungi is urea, which is our typical “animal” compound. And they are rich in amino acids, more like an animal product than a plant one. Not to mention that under the influence of sunlight, even picked mushrooms synthesise vitamin D2 from ergosterol, a molecule similar to human cholesterol.

The mouse sighed and carefully touched the mushroom.

“Let’s move away from these mushrooms,” he suggested to the girl mouse, “With such incomprehensible DNA, they can even start talking to us. And then, you feel that they have some kind of peculiar smell. I would even say that mushrooms smell like our native burrow, where it is always damp and mouldy.

“Chemists all over the world study the smell of mushrooms,” the girl mouse said, breaking off a piece of a porcini mushroom. “The smell of mushrooms is created primarily by eight-carbon alcohols and ketones. The smell of the forest, moisture, greenery — these are hexatomic alcohols, for example, 3-hexanol. The specific aroma of dried mushrooms is formed by derivatives of furan, pyrazine and pyrrole.”

“Such complex concepts seem to make me thirsty,” the little mouse looked around the refrigerator. “Is there any milk here?”

Chapter 9

Evolving Milk

The girl mouse turned her head and showed her friend to the very top shelf, where there were bottles of white liquid.

“Here it is. Help yourself, Tailless.”

The little mouse jumped happily. He quickly found himself on the very top shelf and began gnawing small holes in each bottle of milk, from which a whole fountain of familiar treat immediately poured out onto him.

The girl mouse was watching with a smile how the little mouse was drinking milk from each bottle in turn, and as his round belly was becoming even rounder.

Having taken a sip from another bottle, the little mouse winced and snorted menacingly:

“There is no milk in this bottle at all! There is some kind of sourness here!”

“What are you saying,” the girl mouse squeaked in surprise.

She went up to the bottle from which the little mouse had just drunk and took a sip.

“We’ve come to this, Tailless,” she laughed. “You don’t know the taste of sour milk.”

The little mouse frowned. He was upset that he didn’t know something again.

“I know everything,” he objected to the girl mouse, “Sour milk is when it has gone bad. I just don’t understand why they put it in the refrigerator instead of throwing it out.”

“You don’t know anything,” the girl mouse said sternly. “Milk souring is not so bad if you make this process controlled and monitor how fresh and high-quality milk is fermented not by some random bacteria, but by those specially selected for this purpose. You can add a spoonful of sour cream to the milk or throw in a crust of black bread, you can buy a ‘branded’, guaranteed healthy starter.”

The girl mouse put her paws to her chest and began to dance: she again imagined herself as a housewife in the kitchen. Her dreams were interrupted by the voice of the little mouse:

“Why spoil such good milk with some bacteria?”

“Because fermented milk products are a brilliant biotechnological solution of our distant ancestors. Firstly, an acidified environment is less attractive to harmful bacteria than sweet milk. Secondly, the organisms of many adults do not digest lactose, but they can eat fermented milk products, because the microorganisms in sour milk or kefir work on the principle of ‘so that the goat eats the weeds, but does not touch the peas’ — they consume lactose themselves, and leave other useful substances for us.”

“That is, nature has arranged everything so cunningly,” the little mouse said, calming down. “Understanding that for a baby, milk is the only food, and lactase is produced in its small intestine that is an enzyme that breaks down lactose into glucose and galactose, which are absorbed into the blood there, but in many people, when they leave infancy, active lactase becomes less and less. And if such a person drinks milk, lactose gets into the large intestine, goes to local bacteria, they actively feed, multiply rapidly and are happy… but their owner experiences serious discomfort. Nature acted wisely so that the grown-up individuals would not take away the food resource from the babies.”

“You speak correctly, Tailless,” smiled the mouse. “This is an example of the evolutionary change in humans that arose and spread practically in front of our eyes. The lactose tolerance gene appeared in Northern Europe around 5000 BC, and it is there that it can be now most often found; however, even in this region there are people who do not benefit from milk. For them, there is lactose-free milk and traditional fermented milk products.”

The little mouse winced:

“What could be worse than lactose-free products? This is some kind of stupidity.”

“Stupidity or not stupidity…” the girl mouse drawled. “Yoghurt generally contains Bulgarian bacillus (a special type of lactic acid bacteria) and thermophilic streptococcus. These two love warmth, so they ferment yoghurt at 42-45 °C. Kefir contains kefir fungi, a symbiotic community of beneficial bacteria and yeast.”

The mouse also wanted to talk about milk sterilisation and TetraPak, but her speech was interrupted by a sharp bang. It was so loud that the light in the refrigerator went out, and the girl mouse automatically curled up into a ball.

Chapter 10

The Slippery Pleasure of Maraschino

“Probably Tailless has chewed through the wires,” she thought. “Otherwise, how to explain the bang and the abrupt switching off of the light?”

She made sure that the refrigerator door was still open and began to slowly climb down the shelves. Her and the little mouse’s culinary adventure no longer seemed so fun to her.

“A cocktail, Madam?”

She heard Tailless’s familiar voice.

“Phew, you’re alive!” she exclaimed, seeing the silhouette of the little mouse, who was holding something resembling a cherry in his hands.

“While you were examining the milk,” the little mouse began to justify himself, “I saw a bottle of wine in the refrigerator. Apparently, the owners of this kitchen did not finish it, because the cork was sticking out of the bottle. I walked on it, it detonated and shot straight into the light bulb, it broke and went out.”

The girl mouse shook her head.

“But,” the little mouse smiled proudly, “I found this! It looks like a cherry, but more slippery and much sweeter.”

The girl mouse took a closer look at the little mouse’s find. It was really a cherry.

“It’s a Maraschino cherry,” the mouse said. “Now such cherries are really slippery, red and sweet and are used mainly to make Vermouth cocktails, sundaes and fruit pies.”

“And what happened to them earlier?” the little mouse asked, biting off a piece of the cherry and squinting contentedly.

“And earlier, in the 19th century, such Maraschino cherries were grown on the Dalmatian coast,” the smart girl mouse answered him. “They were soaked in sea water and then preserved in a liqueur made from their own juices, as well as leaves and crushed seeds. The fruit first arrived on American shores as a luxury item at the turn of the century, and Americans happily sipped on fake maraschino cherries, usually flavoured with vanilla or almond. But when word got out about how they were made, people began to resent them. ‘Maraschino Cherries Violate Pure Food Act,’ read one 1907 newspaper headline. According to another one, the fruit was smoked in sulphur and packed in a toxic chemical brine before shipping; at the factory, it was soaked in sugar syrup, flavoured, and dyed red with aniline, a toxic dye made from coal tar byproducts. So many fake maraschino cherries hit the market — some were alcoholic, some were not — that in 1912, the Food and Drug Administration issued an official statement about the difference between real maraschino and the fakes. But none of those alarming discoveries stopped people from eating the candied treats.”

“Because it’s beautiful,” the little mouse said, finishing his cherry, “and because this cherry for drinks reminds me of an explosion of sweetness from childhood.”

________

“And yet, I don’t understand, Smith, why if mice pair up, then one of them must necessarily be smart and the other stupid,” the scientist asked, watching two mice sitting in a cage taking candied cherries from each other.

“An instinct,” the second scientist laughed.

“Or this phenomenon will remain unstudied,” the third one shrugged.

After looking at the mice again, the scientists left the laboratory. Thinking about how to subdue biomolecular condensates, the scientists did not notice how the two mice waved after them. One of the mice had no tail.

The Einstein-Rosen bridge? We’re building it out of facts.

Thank you!