Ode to tetris: the true story behind the iconic game

The history of the creation of this invention resembles a real spy detective story, in which everything is mixed – superheroes and corrupt victims of politics, endless changes in time zones, chases, falsified documents, differences in ideological views,

blackmail and even shootings. Therefore, we decided to write the article in the spirit of a spy comic, which is not quite standard for a popular science publication and is completely non-standard for describing any inventions.

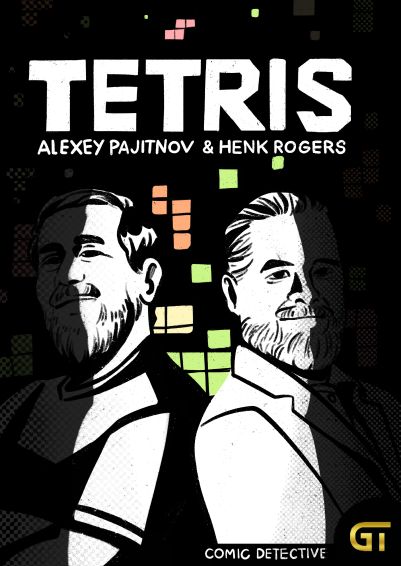

Main characters:

- Alexey Pajitnov – an ordinary Soviet citizen, engineer and employee of the Computing Center of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- Hank Rogers – American game designer and entrepreneur

Key figures:

- Pentamino and Solomon Golombo

- Robert Stein

- Alexander Alekseenko

- Computer “Electronics 60” and Russian-folk melody “Peddlers” – ta ta ta tatata tata tata ta tatata tatata

So the story begins.

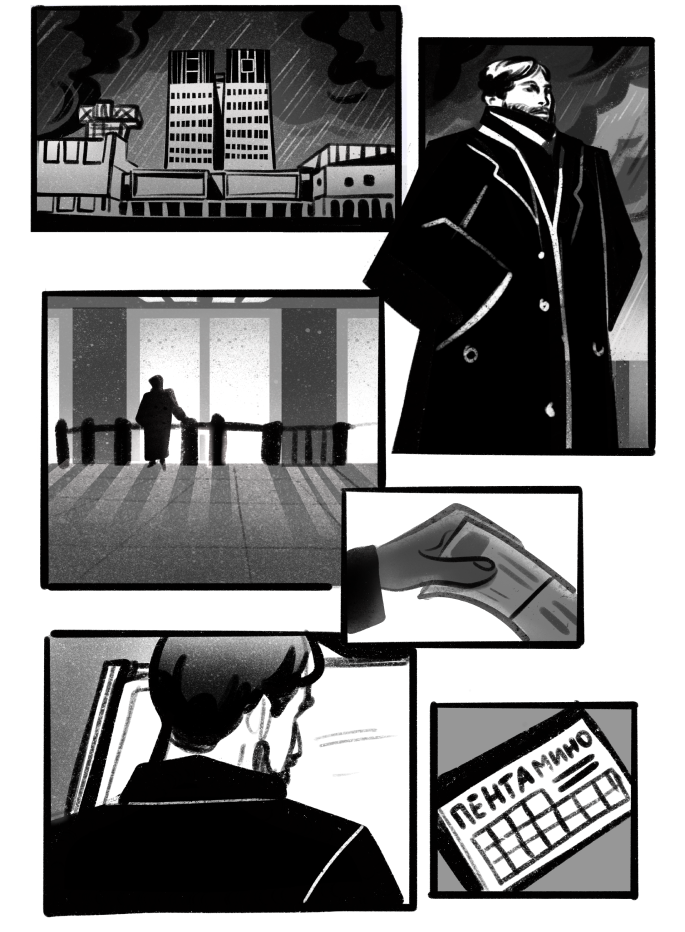

1985, Moscow

An ordinary Soviet engineer rushes to work. A gray sky hangs above the gray streets and periodically generously waters the city with cold and furious rain. The engineer wraps himself deeper in a prickly scarf and puts his hand into the pocket of his gray jacket, inside of which, in a small shabby box, lies a popular game of that time called Pentomino, where curved figures need to be assembled into a single unit.

The engineer’s name is Alexey Leonidovich Pajitnov and today is his regular working day. At the center of the Academy of Sciences, Alexey must test the power of equipment that goes to the computer center, but the Soviet engineer decides to approach even this task creatively, so he comes up with various non-standard puzzles for smart computers.

The USSR Academy of Sciences itself allows employees to work overtime on their own projects and sees nothing wrong with employees staying late at work to come up with new ways to test capacity. That’s why Alexey Pajitnov doesn’t sleep at night, but dresses up in a Batman costume, clears the streets of Moscow from bandits and develops games.

Alexey entered the building, showed his pass and quietly went to his workplace. He took off his wet jacket, hung it on a hook, before taking the battered box with the game from his pocket and turned on the computer.

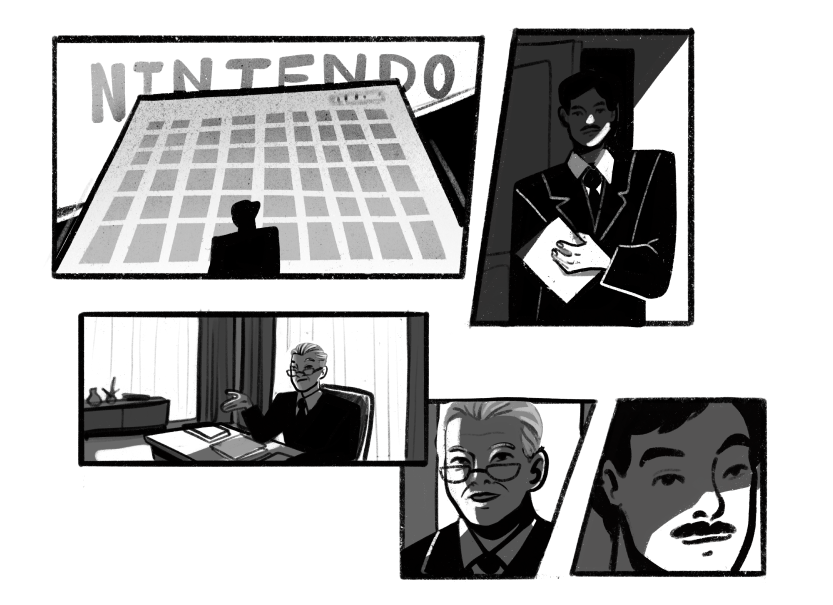

1988, Game Show exhibition, Las Vegas

Bright neon lights dazzle visitors and attract promoters. Slot machines of various types and modifications shimmer in the sun and make various sounds, inviting and luring every visitor into their gaming world. Every now and then the clink of scattered coins is heard, which is interrupted by the hum of voices of people dressed in expensive suits talking on the phone: “Yes!! Yes! We are signing an agreement with them! How do I know? We already have the patent and license! Fly to their office immediately!”

A young man in a strict business suit confidently walks between the rows of colorful cars. Before coming to the Game Show, this brown-eyed young man had already flown 2 million miles and had already been to the Consumer Electronics Show, visited a huge number of exhibits in Japan and China, and also closed deals in Korea and in places better left unsaid.

The young man’s name is Hank Rogers, and his main task is to look for interesting games that can then be sold in Japan. Nice job! And now he is confidently walking between the aisles with various game consoles, because he knows exactly what he needs to find.

A few years earlier

Hank confidently strides into the Nintendo office to make his first deal, which will make him a publisher and partner of the Japanese company.

Hank Rogers received a personal invitation from Mr. Yamauchi in response to an offer to improve Nintendo’s newly released Go game.

Mr. Yamauchi kindly invites Hank Rogers to take a seat at the table, but Rogers immediately gets down to business, “I can make a game for your consoles, remake its graphics and adapt the music without touching the algorithm.”

To which Hiroshi Yamauchi responds, “I won’t be able to give you programmers, but I can give you $300,000. See you in 9 months.”

Exactly 9 months later, Hank Rogers appears again in Mr. Yamauchi’s office to announce that the game has been improved and new characters have appeared in it. However, Mr. Yamauchi cannot appreciate the gamepad, so he gives the game console to his assistant, who wins in the game and convinces the President of the Company that the new version of the Go game is too simple for Nintendo.

In response to this, Hank Rogers objects, saying that it was a miracle that the game was launched on a simple console and offers to publish the game by Nintendo and pay Mr. Yamauchi a dollar for each cartridge sold until he returns the capital spent.

The offer turned out to be fair, and the President of the Japanese Company, together with Hank Rogers, shook hands again: Hank went to make master copies of the game, while simultaneously inventing a new product for the gaming industry – Black Onyx, and Mr. Yamauchi went to wait for the promised amount of money.

A few more years earlier

Budapest. The not very bright sun illuminates the newly awakened capital of Hungary, passing its rays along Andrássy Avenue and painting the opera buildings, the Royal Palace and the funicular leading to Castle Hill with bright colors.

Not noticing all these beauties, a gloomy man in the same gloomy brown cloak walks through the city. His name is Robert Stein, by birth he is a native of Hungary, and by vocation he is a cunning British intermediary who came up with the idea of periodically traveling to the countries of Eastern Europe and spying on things there, after which reselling the ideas he saw at exorbitant prices in the West.

It was difficult to surprise Robert Stein, but now he stopped in front of a group of locals who, sitting in front of the hefty computer monitors of that time, were playing a game in which figures made up of four squares were moved from top to bottom of the screen. Moreover, the users were playing an already localized game in English.

Robert Stein watched the game for a few more minutes, shifting from foot to foot, turned sharply and quickly walked into a large glass building nearby, from where he could send a fax.

1985, Moscow, Building of the Computing Center of the USSR Academy of Sciences

Alexey Pajitnov sits at the computer and smokes Belomor cigarettes right behind the computer screen. Puffing cigarette smoke at the dozen people who work with him in the same room, Alexey decides to create a live and computer analogue of the game that was in his jacket pocket – Pentomino.

According to Alexey’s idea, the game should take place in real time, where shapes made up of square brackets should smoothly descend into a strictly designated piece of the playing field and turn around their own center of gravity, but the technology of that time didn’t meet such gameplay innovations and features, and FPS was not yet heard about.

Therefore, the future creator of the world game made a wise decision to reduce the shapes to four – as a result he got tetrominoes.

To implement his plan, Alexey uses the only programming language understandable for the Electronics 60 computer – Pascal – and opens a second pack of cigarettes. He diligently writes parentheses on the screen when suddenly the phone rings.

“Alexey, don’t forget to take the children to tennis today,” a kind female voice tells him.

“Tennis,” Alexey repeats into the phone, “Tennis.”

He sits down at his computer again and on a blank sheet of paper, where “Tetromino” was previously written, he writes the word “Tetris”.

1988, Las Vegas, gaming exhibition

Hank Rogers confidently walks past the slot machines when he notices on the screen of one of them figures consisting of squares falling down. The background for the falling figures was an image of the red stone Kremlin, the slot machine featured a hammer and sickle and it was written that that was the first game to come to the gaming market from the Soviet Union. Also a respectable man was standing next to the console. He explained that all rights to the computer version of this game belonged to Mirrorsoft.

Hank watched, fascinated, as figures of different colors slowly descended to Russian folk music, forming rows and other, more bizarre patterns. After completing the game levels, a word made up of those very square figures appeared on the screen – Tetris.

“Tetris,” Hank Rogers whispered enthusiastically and headed to the airport with the same confident step.

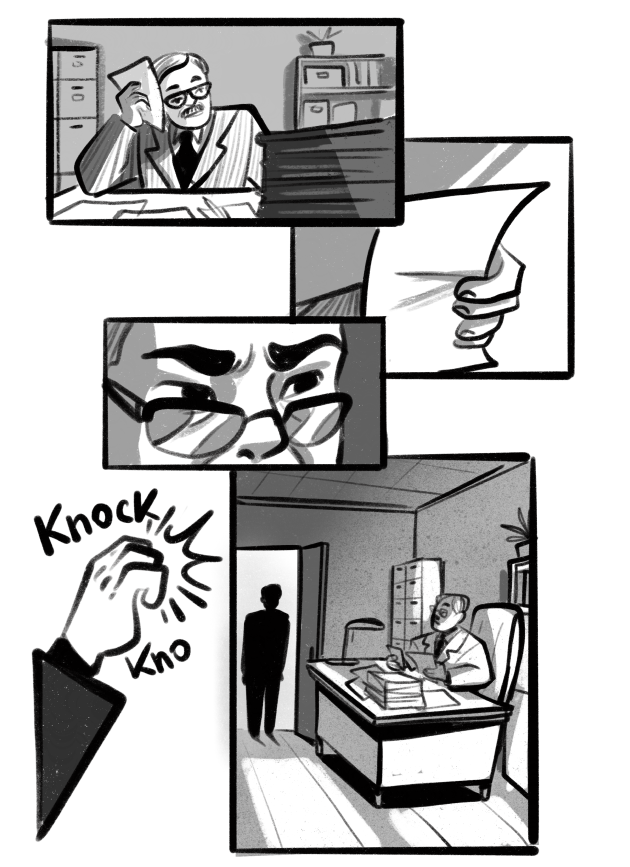

1986, Moscow, the building in which the Elektronorgtechnica company (aka Elorg) was located

A man is sitting at his office desk – an employee of the Elorg company, who has been trying for several hours to clear out a pile of accumulated papers, among which were recently received faxes – messages from Bulgaria that some unprecedented Soviet game has become so popular that they want to regulate its release at the state level.

ALexander Alekseenko, that was the man’s name, read another fax in Bulgarian, went to the window and thought. No one in the USSR had ever before faced the need to issue licenses, since the circle of software users was very narrow: there were no real games on electronic computers, they were mainly programs that simplified some work tasks in certain areas, calculated statistical data and helped generate reports and manage systems.

And home personal computers were so rare at that time that their owners literally knew each other by sight.

Therefore, if programs that went beyond work tasks were in demand, it was very small, and the programs were simply sold at a fixed price without any license. In addition, licensing would involve the transfer of rights, and no one ever asked the question of copyright in relation to computer programs in the Soviet Union. Copyright at that time protected only literary, artistic and musical works, but that did not apply to computers. The released programs were considered state property, but the use, distribution and modification of their developments was the absolute prerogative of state enterprises and institutions, and therefore no licensing issues arose. It was believed that if a programmer wrote some kind of program while working at an enterprise in a computer center, then the program belonged to the computer center.

Alexander’s thoughts were interrupted by a knock on the door. Alexey Pajitnov stood on the threshold of his office.

1987, Budapest, unknown building from which you could send fax messages to the Soviet Union

Robert Stein has already been walking around the wall for the 20th time, pacing the room in anticipation of a fax message from the Soviet Union. A few days ago, he had contacted the Russians by fax and, through the Soviet company Elektronorgtechnika, requested permission to distribute Tetris on computers.

Robert Stein felt that that day he would be lucky and the Soviet side would give him a positive answer. He continued to walk around the room, occasionally glancing at the pretty typists and silent fax machines, imagining how, if the answer was positive, he would successfully sell all the rights to the bombing game to Robert Maxwell, the owner of the British company Mirrorsoft.

On that day, Robert Stein’s intuition did not fail, the Union gave the go-ahead for the distribution of Tetris on computers, and the enterprising businessman immediately went to the phone to dial the number of the owner of Mirrorsoft.

1988, Nintendo headquarters

Mr. Yamauchi looks at Rogers Hank in bewilderment, “Tell me again, Mr. Hank, what should I give you a loan for again?”

Hank Rogers sighs and repeats his story about how, at an exhibition in Las Vegas, he saw a game that was unlike anything the whole world had seen before. He tells the head of Nintendo that despite all the abstractness, Tetris is similar to the familiar life in which we are forced to solve accumulating problems on the go, which fall in the form of various figures on us every day.

Hank also mentions the famous Tetris effect – after playing it for several minutes, figures made of squares and combinations of them become so ingrained in the memory that they even begin to appear in dreams.

This is due to the fact that if a person is engaged in some kind of mental activity associated with visual symbols for a long time, images of these symbols then appear in his mind: for example, musicians often continue to play notes in their sleep after memorizing a melody during the day, mathematicians see dreams with mathematical formulas, and sailors, after a long stay at sea, continue to feel the effect of pitching and this is funny reflected in their gait.

Mr. Yamauchi listens carefully to his interlocutor, but recognizes all his arguments as unconvincing and reminds Hank Rogers that all rights to the Tetris game, which amazed him so much, already belong to the Mirrorsoft company.

Then Hank pulls out a convincing trump card and says that he can negotiate with a cunning entrepreneur from Budapest, Robert Stein, to transfer to him the rights to publish the game on game consoles. Computers were widely considered an irrational luxury at the time, and a gaming console was cheaper and could fit into a pocket or travel bag.

Hank Rogers is so convinced of the correctness of his decision that he agrees to mortgage his wife’s parental home to ensure his words.

1988, The USA, Wall Street

Hank Rogers approaches a surly man in a surly suit and asks him to sell him the rights to Tetris for all handheld devices.

Robert Stein looks around and convinces Hank that everything is complicated, that cooperation with Mirrorsoft is not going so smoothly, and in general Alexey Pajitnov himself will most likely be against such an outcome.

Then Hank Rogers makes the most fateful decision in his life – he informs Robert Stein that he is flying to Moscow.

1986, Moscow, the building in which the Elektronorgtechnika company (aka Elorg) was located

Alexander Alekseenko extends his hand to Alexey in greeting. Confused, Alexey sits down on a chair and begins to talk confusingly that he has a very funny program called “Biograph” and he would like to talk about the possibility of selling it.

To win over his interlocutor, Alexander casually asks about what other games Alexey is interested in. He shows him another game and demonstrates Tetris along with it.

Alexander, impressed by the Tetris graphics, unusual for those times, puts his hand on Alexey’s shoulder and decisively says: “Alexey, you have made a real bomb! I’m so impressed that I am still getting goosebumps! Of course I will sell your Tetris!”

To which Alexey meets with a condescending smile: “Many have tried.”

Alexey wearily looks away and tells Alexander that some time ago he corresponded with a certain gentleman from Hungary, whose name is Robert Stein. Correspondence, which he regrets about, because for Soviet times and the conditions of the Iron Curtain it was not very neat. Alexey told Alexander that Robert Stein had offered 10 personal computers in exchange for full ownership of all rights to Tetris.

However, Alexey, knowing the harsh laws of the Soviet Union regarding copyrights, understands that for his game he is actually an “inventor”, and understands that all rights can only belong to state-owned enterprises, one of which is Elorg.

He looks at Alexander again, “Alexander, I transfer you the rights to Tetris. It will be better this way.”

Alexander carefully sits down on a conveniently located chair and feverishly begins to rub his temples with both hands: “Alexey, let’s make a new fax message.”

1987, Budapest

Robert Stein shakes hands with the three gentlemen and closes the door tightly behind them. He has just sold the rights to use the game Tetris to Sega and now he needs to arrange everything so that the Mirrorsoft company, where he also sold the rights to use, does not find out about it.

Robert went to the mirror and smiled at his reflection.

He will think about Mirrorsoft tomorrow; today he needs to prepare a deal for the Atari company, which also dreams of getting the right to release the game on personal computers.

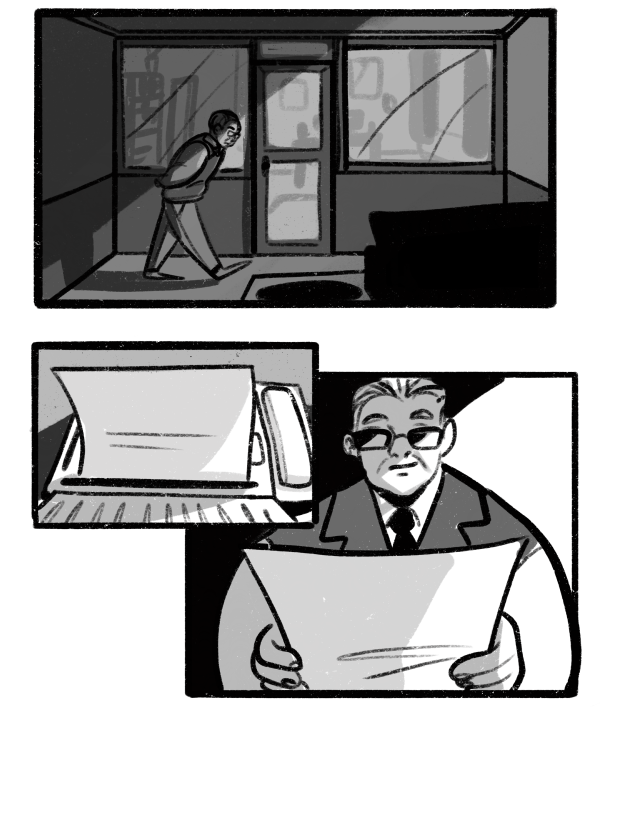

1988, Moscow, Sheremetyevo airport

“Attention, the flight has landed…,” the announcer’s microphone began to wheeze.

Hank Rogers looked around. It seems that only at that moment he began to understand that he had flown almost 8,000 miles for the sake of a game on which he had bet everything – all his money, real estate, reputation, years of work in the gaming industry and the bright future of all his children.

His thoughts were interrupted by the voice of a woman – a representative of customs control, “Citizen, do you speak Russian?”

Hank shook his head.

“It says here that you are Danish. Have you arrived from Denmark?”

“No, I’m Dutch,” Hank objected when he heard the name of the country.

“But it’s written in your documents that you’re a Danish,” the customs worker continued.

Hank became noticeably nervous. The woman in uniform left, taking his documents with her. Hank had no choice but to enjoy the view of the lonely window of the Soviet customs.

Moscow greeted Hank with wet snow and puddles.

1987, Budapest

“Are you feeling bad, Mr. Stein?” the young girl asked, kneeling down in front of the businessman.

A couple of times a week she visited the company’s office, sorted mail and carried out other assignments for Mr. Stein.

Entering the office, the girl saw overturned chairs, scattered papers and her boss lying on the floor.

“Do you feel bad?” she repeated her question.

“Thank you,” Stein answered her, “I’ll do it myself somehow.”

Robert desperately needed her help, but at that moment he could not admit to his pretty employee that he had suffered because of his own greed, because that morning representatives of Mirrorsoft visited his office and hinted, in such a frightening way, that Robert should not do business with competitors.

1988, Moscow, the building in which the Elektronorgtechnika company (aka Elorg) was located

Hank Rogers quickly walks towards the stairs leading to the second floor, not paying attention to the surprised faces of the employees and the insistent female voice from behind:

“Citizen! Citizen! You cannot enter the building without a pass! Citizen!”

Hank was unstoppable. At that moment, he himself did not understand where he got so much determination from: either he did not want to return empty-handed to Japan, or he did not want to lose the home of his relatives, or he was driven by a banal fear of being recruited by Soviet intelligence spies who were hiding literally around every corner. At least that’s what Robert Stein told him.

An Elorg company employee named Belikov came out of his office and, blocking Hank Rogers’ path, sternly asked: “What’s going on here?”

Hank began to explain that he had come to Russia in order to obtain a license to release the Tetris game on portable consoles and that several companies around the world were releasing the game on Gameboys without having the rights to do so, which meant that all pirated copies must be destroyed.

Belikov, not understanding a word of English, without taking his eyes off Rogers, shouted into the darkness of the corridor, “Does anyone here speak English? Comrade Alekseev, it seems that you have already signed some documents with someone for the release of the game, haven’t you?”

Alexander Alekseev left the office.

1988, Moscow, the building in which the Elektronorgtechnika company (aka Elorg) was located

Alexander Alekseev moves to the window, while Alexey Pajitnov in bewilderment examines the bright boxes with the Tetris game laid out on the table in front of him. He picks up a piece of red cardboard and reads the yellow inscription on it in English – the first game of the Union.

Hank Rogers watches this with interest, trying to guess what Alexey is experiencing at this moment – pride or anger?

Alekseev interrupted the silence:

“We did contact Mr. Stein,” he said in the businesslike tone of a Soviet citizen, “but we did not transfer the rights to the game to him. We gave him the right to sell copies of the game for computers. Moreover, Robert Stein never fulfilled the second part of the deal.”

“That is because the company Mirrorsoft is now bankrupt. Robert Stein skillfully bluffed, selling licenses for the production of Tetris to monopoly companies, and that is why we can now see many such illegal boxes in front of us,” Hank calmly explained to his interlocutor and looked at Alexey again.

He continued to look at the blanks with childish delight, in the middle of which was the letter “T”.

“Understand me right, Citizen Alekseev,” Hank continued, “I’m here to buy from you the right to publish Tetris on portable devices, we have already purchased a sufficient number of consoles for the Japanese market. I myself will add some game mechanics to Tetris to make it even more popular. And all the money from the deal will be yours, Alexey.”

Alexey Pajitnov, hearing his name, looked up from looking at the boxes with his game and answered embarrassedly: “But according to the law, I cannot take money for my invention.”

Hank stood up, took a couple of steps around the office, then sat down opposite Alexei again: “Well, then, do you want to build your own project or company in this case?”

During that meeting, Alexey more than once approached the computer and showed Hank and the amazed Alexander that very first green version of Tetris with square brackets, which he developed himself on one gray rainy working day.

After Hank Rogers’ visit to Moscow, Alexey was contacted by representatives of Sega, Mirrorsoft, Atari and other companies to which the dodgy Robert Stein was selling a non-existent license.

Alexey Pajitnov was pressured even by members of the CPSU Central Committee, who were concerned that the Kremlin loved playing Tetris. All the events around the famous game developed during the collapse of the Soviet Union and “Tetris” became a harbinger of the inevitable onset of capitalism, the tempting offers of which even the most principled communists could not resist. And some European publications even blamed Tetris for the collapse of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the country’s economy.

Later, Alexey Pajitnov will agree to Elorg to issue a license to Hank Rogers to sell Tetris around the world. By that time, Hank, while porting the game to Nintendo consoles, added mechanics to it that helped Tetris become popular throughout the world. With Alexey’s permission, Hank reworked the original Tetris and made many changes for the Japanese market, adding bonuses for single doubles and rewards for collected rows. However, the copyright for the game still remained with the company that Alexey had once contacted. Alexey managed to return the rights to the game only in 2005, when, after long trials to establish the authorship and negotiations with the current bosses, his friend Hank bought out the Elorg company itself.

There were lawsuits between Nintendo and Atari, in which Nintendo was able to prove the difference between a personal computer and a game console.

Alexey Pajitnov moved to San Francisco, where he lives up to today.

The Tetris game still lives and continues to gain new fans: as history shows, every new technology gives new breath to Tetris, and now, with the advent of virtual reality, one of the best versions of the game has appeared. However, in addition to the official versions of Tetris, analogues that use the same mechanics, such as Tetrio and Jestris, constantly appear on the Internet. Invented in the distant Soviet Union, the game continues to live, develop and is not going to stop, demonstrating to all of us the amazing phenomenon of eternal life.

Once a humble engineer ushered in a new round of human evolution, a determined game designer and entrepreneur helped civilization make a massive transition into the era of gaming, and the Tetris game itself paved the way for a future that has already arrived.

Now the creators of Tetris, having gathered their stable ranks from squares scattered by fate, continue to live, play Tetris and change our planet for the better.

It’s raining…

The atomic fortress has fallen. And our hair stands on end!

Thank you!