Music is the mind embodied in beautiful sounds. Global Confession of Global Musicians Anna Lisianskaia and Nikolay Latyshev

Undoubtedly, everyone needs something sacred to which they can return time and again, like retreating under a blanket with a cup of hot tea after being out in the cold. These sanctuaries can be habits, people, places, books we’ve read, and of course, music. Throughout life, music accompanies people in a variety of situations; it is everywhere: in nature, in words, and even in silence.

Why are classical musical works more complex than modern ones? How can one decipher the composer’s intent, and to which science is music most akin? The editorial team of The Global Technology magazine posed these questions to global musicians of our time. The ones answering honestly and openly to the modern inquiries about classical music were:

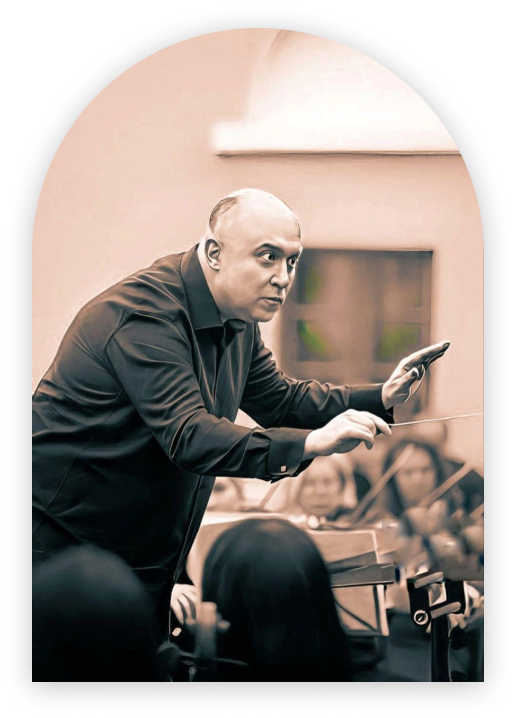

Nikolay Latyshev, Candidate of Art Criticism, conductor of the children’s pop-symphony orchestra “Plamya” at the Grieg Children’s Music School in Moscow, conductor of the children’s pop-symphony orchestra “Debut” at the Shalyapin Children’s Music School in Moscow, conductor of the “Voskhozhdenie” orchestra, musicologist, and teacher of music theory at the Prokofiev Children’s Music School in Moscow.

Anna Lisianskaia

Laureate of international competitions, graduate of the Gnessin Russian Academy of Music, harpist of the N.I. Sats Children’s Musical Theater and the Moscow Operetta Theater.

— Anna, Nikolay, thank you for agreeing to this interview. I would like to start with an unusual question: at what moment does a musician become a musician?

— Thank you for the question. In my opinion, it is quite ambiguous. There are indeed people who work as musicians but are not musicians by birth, and there are musicians who do not know musical notation. Can one immediately become or be born a musician? We could discuss genetics, gifts, or talents, but what truly distinguishes a real musician is diligence. Did you know that both hemispheres of the brain are activated during music practice and that music has a significant physiological component? The profession of a musician is similar to that of a doctor, where one must continually develop and refine their skills every day, every minute. Besides being able to play well, a musician needs exposure, experience, intuition, and taste, which do not simply appear at the snap of a finger.

— I would also like to answer the question “When does a musician become a musician?” Let’s break it down: who exactly is a musician? I have participated in folklore expeditions and recorded rituals where music played an important role. Can we consider the elderly women who sang during these rituals to be musicians? In my view, yes.

When I was teaching at the conservatory, we had a policy of allowing free attendance at lectures, and I noticed a mysterious girl attending each session. She fully understood that she wouldn’t receive a diploma for attending various lectures, but that wasn’t her goal. She valued the knowledge and the music itself. Can we call her a musician? Absolutely. Can an engineer you meet during the intermission of an opera at the Grand Conservatory analyze a piece like a professional listener? Yes.

Does a composer, while writing a piece, know that it might inspire someone to a heroic deed in the future? No. Even works performed during a composer’s lifetime were not always warmly received by the public, and many pieces were written “for the drawer.” But does that mean the composers stop being composers? No.

In my opinion, a musician is someone whose life is deeply connected to music and who actively engages in musical activities.

— Please reveal to our readers: how do you, as a professional artist and a professional conductor, manage to flawlessly interpret and convey what the composer intended with their work? Is it possible to decipher the musician’s intent?

— It should be noted that classical musical works are always performed through interpretation. Our task, and the task of performers, is to learn to view a piece from different perspectives. In reality, we are not burdened with “deciphering” the composer’s intent; we must marry our individuality with the composer’s vision, referring to their creative notes and setting aside our own egos. Deciphering a musical work’s intent is impossible, and perhaps not even necessary. Even by studying complex scores, manuscripts, the biography, and life of the composer, we are unlikely to experience the exact emotions or moments they did while creating the piece. The composer’s goal is to write music using their unique musical language, and this is about genuine sound art, which doesn’t always require explanation.

— There’s a saying: “Talking about music is like dancing about architecture.” There was a funny incident when a husband and wife decided to visit an art exhibition. The wife wandered through the halls, eagerly examining the paintings, while the husband became more convinced that he understood nothing about art. “How can you not understand art?” the wife asked with a smirk. “It’s obvious – this is the sky, these are flowers.” “Hunger. War. That’s the title of the painting,” the husband replied gloomily after reading the artist’s caption. People listen to music and like it because it is relevant and contemporary, because it triggers special processes within them. Or people don’t listen to music because it doesn’t have current significance for them, and the composer’s intent has nothing to do with it.

— Let’s dream and travel back in time. If each of you had the opportunity to be next to your favorite composer for a moment, who would it be and what would you say to them?

— I would like to see Dmitri Shostakovich. I would approach him, place a hand on his shoulder, and say, “Your music will be played on stages all over the world!”

— Hmm… I would gladly shake hands with Sibelius, Glazunov, and Scriabin, and thank them for their beautiful music.

— Some musicians say that music is similar to mathematics.

How do you feel or perhaps see music?

— You know, when I first entered the world of music, even during my student years, music truly reminded me of the queen of sciences. I wanted to organize everything into intervals, harmonies, and other equally interesting components. Over time, my opinion regarding whether music can be counted changed. Music is ultimately not about the precision of sciences; it’s about the soul. Sometimes my students ask me to let them play a certain piece, and I realize that technically it will be performed excellently, but can a person play about pain, about experiences, about moments of absolute happiness, emotions, and feelings they haven’t yet experienced? Now, music is like an interesting movie playing inside my head. It’s cinema, it’s the soundtrack of actions happening within me.

— I probably see music differently every time, depending on the piece and, as Anna rightly noted, depending on what I’ve lived through, experienced, some life experiences. For example, I never felt any special emotions when listening to the works of Jean Sibelius; he didn’t evoke anything particular in me. But at some point, a significant event happened in my life – a significant journey, after which I looked at the compositions of this composer in a completely different light. My perception of music depends on the specific composition. As for science, I would compare music, perhaps, to the science of languages, to linguistics. Or to the science of intuitively comprehended meaning, but there is no such science.

— The next question will be very candid. Have you had any life experiences where music specifically helped you?

— Music permeates every aspect of human life; for some, it’s constantly playing through headphones, for others, it’s in the background from radios, some sing, some play. Music was a universal remedy for me; it was my friend who helped me with introspection, immersing me in certain states. Sometimes I need classical music, and sometimes I need music with lyrics. Sometimes I need classical music, sometimes I need music with lyrics.

— You asked that question, and instantly, I was submerged in memories. Certain pieces of music are intertwined with different periods of my life. The first movement of Glazunov’s Fourth Symphony, Mahler’s Adagietto from the Fifth Symphony… I’m sorry, but it’s too personal.

— Let’s return to contemporary realities then. Why is the common belief that classical music is complex while pop and any modern music are simple so prevalent?

— Agreeably, it would be odd if instead of the usual, understandable bedtime stories, we suggested children read Ray Bradbury’s “Dandelion Wine” or works by Dostoevsky. Taste in different music genres is cultivated from early childhood and absorbed like mother’s milk. I find it hard to agree with the assertion that modern music is simpler. If you analyze some contemporary pieces, you’ll find complex harmonies and their own unique language. It’s just that modern music has become more accessible to listeners nowadays, hence seems simpler. People now have choices in music from a young age; every child can form their preferences from childhood. Additionally, historical moments also influence the audience’s taste. Any music is beautiful, but beauty doesn’t necessarily have to be complex. It’s life, it’s the passage of time.

— I believe that every piece of music has the right to exist. Even in classical music, there are compositions built on primitive harmonies. The language of “mass genres” music is simpler. Even more so, a language that is simpler to understand is more accessible and comprehensible. Regular rhythm is understandable, the predictable change of harmonies is understandable; you don’t need to strain to understand such music. Classical composers, on the contrary, often think more complexly. One could say that understanding classical music and cultivating listeners in tonal thinking is an educational issue. In my opinion, we just need to listen to more good music, including classical.

— But some musicians try to bridge the gap between music and contemporary realities through remixes. How do you feel about this? Is it worth making covers of classical music?

— Here, I still take the position of a “Guardian.” Classical music is unique in its performance, originality, authenticity, and the impossibility of repetition. On the other hand, aren’t we already remixing classical music ourselves by performing it on modern instruments? Perhaps I would consider the permissibility of remixes on a case-by-case basis.

— My opinion is that not all remixes are created equal. I can’t say I see anything inherently wrong with modernizing classical music; sometimes it gives listeners, and even us, a new vision, new opportunities for reinterpretation. If such a path leads to something good, guides people through modern adaptations into classical music or simply into music, then why not? Music helps people better understand their emotions, so it’s easier and more important for a person to hear a piece just like that now.

— Since we’ve touched on contemporary mainstream music, let’s analyze a familiar modern musical piece together, shall we?

— Brilliant idea! Let’s analyze the main theme from “Star Wars” by John Williams. Agree that the piece is written in such monumental orchestral language that without knowing it’s music for a film, one could confidently assume it’s the beginning of some Wagnerian suite. From a symphonic standpoint, the score is so professionally crafted that all musicians wonder: ‘Did the composer really know orchestration so well or did someone later orchestrate the music?’

— I fully agree with Nikolai’s response. John Williams has meticulously written instrument parts. Here, too, we can make reference to the works of classical composers. In some compositions, the composer wrote parts for an instrument without knowing it well. For example, in Sidelnikov’s “Romancero” set to the poetry of García Lorca, there is a part for electric guitar that is impossible to play even for the most virtuoso performer.

In all the music for “Star Wars,” as a performer, I’m pleased that I’m not playing in the orchestra for someone or with someone as a company; I have my own virtuosically written part. And since we’re analyzing a musical piece, I want to highlight interesting harmonies, amazing sound discoveries. Despite the “Star Wars” theme being familiar to everyone, it’s not complex. There’s no complexity in its melody construction or orchestration just for the sake of complexity. The piece is made with love for listeners and performers from beginning to end.

— Last question. How did you get into music, and if your life had turned out differently, what profession would you have chosen for yourself?

— Oh, my entry into music is the favorite story in our family. My mom won a piano in a lottery and took me to music school. I don’t think my family saw me as a “great musician” back then; they just needed someone to play along somewhere, accompany their favorite songs. But the lottery prize and the decision to send me to music school turned out to be prophetic; I got into music and loved it very much. I continue to explore and discover it anew every time. If something had gone differently in my life? I would have become a surgeon, a language specialist, or a train driver.

— It was my grandmother who brought me to music school. The teachers listened to me and immediately put me in the harp class. But one day, during school, I became fascinated with anatomy; I had a big book with pictures, and I wanted to become a doctor. I got so engrossed in reading anatomy, hiding under the covers, that I once set the couch on fire. I don’t know how my life would have turned out without classical music… but I would have definitely chosen a profession based on helping people.

We’ve ventured beyond the boundaries of time and space. By the way, it’s empty there.

Thank you!