Category: Global minds

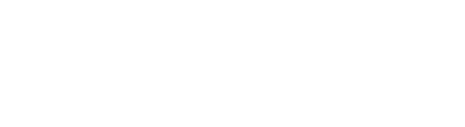

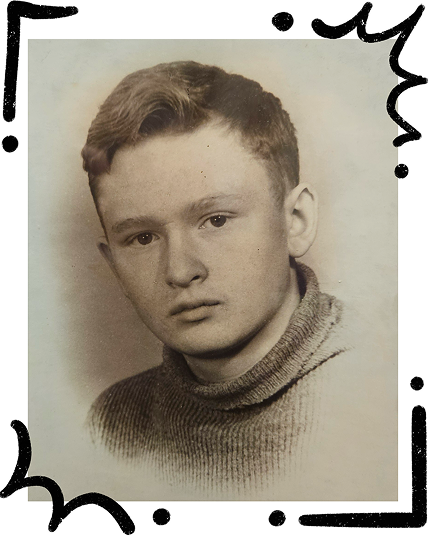

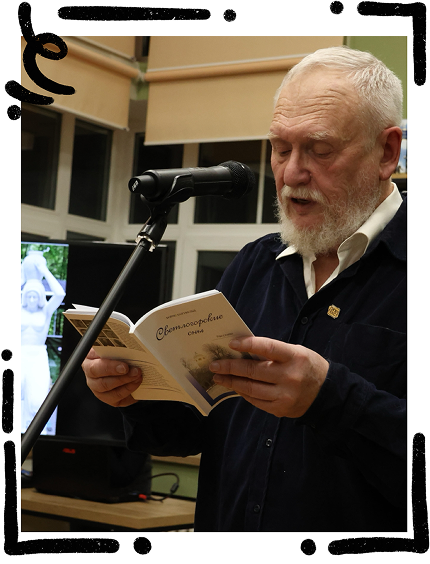

Interview with Boris Bartfeld

“Why do you write these books? No one reads them.” The silence that follows such a statement is suffocating: in it, one can hear the scratch of a ballpoint pen and the dry tap of small keys, shattered dreams of recognition, and half-forgotten words of archaisms. And within that same silence lies the main fear of everyone who has ever been left alone with blank pages.

What is more important: to remain true to oneself or to do what modern algorithms demand? How does one learn to read the audience’s mind without falling into the ugly cliché of “what would you like?” How does one not lose their ‘skein’ of language in the digital noise and not dissolve into the queue for cookbooks?

In this interview, we spoke with our guest about the love of language and literature, about the courage to be the voice of one’s place and time in an era when places are being erased by the digital world and time is accelerating to the point of impossibility. About how to remain a “singer of the native land” when the borders of that land become ghostly, about why a library today is turning into a “maître d’ of culture,” and about the stubborn habit of continuing to write, “preserving oneself, defying fate,” even when it seems that all words dissolve in the white noise of modernity without ever touching anyone’s consciousness.

Our questions were answered by a Member of the Union of Writers of Russia, Chairman of the Kaliningrad Regional Writers’ Organization, Editor-in-Chief of the “Baltika” magazine, author of nineteen books of fiction and poetry, organizer of international literary competitions and festivals — Boris Nukhimovich Bartfeld.

— The internet knows that Boris Bartfeld is a physicist by education, an organizer by calling, and a writer by nature. So who is Boris Nukhimovich Bartfeld in reality?

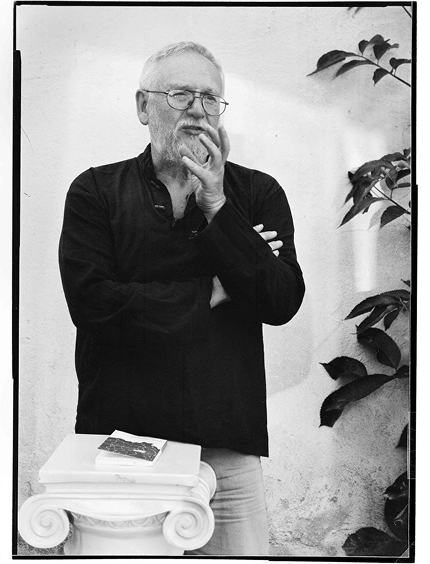

— I suppose I have remained a ninth-grade boy with the ideas I had back then. What was instilled in me during that time is, perhaps, the most important thing in life: the understanding of certain patterns, and the things that concern my interests and directions. Everything that comes from childhood was formed by the ninth grade. Everything that followed is just a slight gloss, a glaze on what was already there in the ninth grade.

What you see before you now is me: a somewhat romantic boy, looking at the world through the eyes of a person heavily influenced by science fiction, who believes in scientific and technological progress, endlessly re-reads his favorite book by Sergei Aleksandrovich Snegov, “People as Gods,” and the magazine “Kvant,” falls in love, anticipates something, and so on. If viewed from the perspective of the inner world, it is probably so.

— Boris Nukhimovich, thank you for this honesty. Often, people engaged in literary creativity stumble upon a simple yet unbearably difficult question: “What is love for literature?”

— I think there will be different answers for an author and for a reader. Speaking of the reader, love has been greatly modified, and on one hand, the love for the literature we know, which we are used to calling literature, is fading. For the author, it is very personal. For example, for me, literature is an opportunity to speak up, to make my voice heard. Every author is a private individual who, however, gains public resonance: not a statesman, not a deputy, just a person. This driving force manifests differently in different writers, but for a great many people, it is the desire to express what has been accumulated and the hope for a response.

— So, is it important, after all, to be heard?

— Well, yes, absolutely. Even if it’s just close people from your own circle — it’s still important to be heard. Today, reading texts, especially long ones, is a tremendous effort. It turns out the reader must exert effort to immerse themselves. As one of my older colleagues used to say: “Soon, a writer will have to pay to be read.” In my opinion, everything is heading exactly in that direction.

So, what emerges is a kind of collaborative effort: a writer now must value their potential reader, cherish and protect them. But on the other hand — they must also sometimes be inconvenient.

— This leads to another important question: “Should authors adapt to the reader, to modern realities, or to society?”

— The word “adapt” is very ambiguous. It has both positive and negative connotations. But one thing is clear: to be met, you have to be somewhere. To meet a beautiful girl walking down the street, you have to go out onto that street. There’s no getting around it.

Choosing a genre is also adaptation. Because you are still operating within a ready-made structure. Being original is wonderful, but I don’t know of anything completely new that doesn’t lean on something created before. Even poets, who work more with form, still exist within these forms that are already established. And it might seem to you that what you’re doing has already been done — and in an even bolder version than yours.

Adapting to themes? In that sense, I’m a very inactive author. But I think guessing, finding a theme interesting for the reader is also important. Nowadays, there’s more and more talk about sensational, extreme plots that provoke interest and curiosity. This is also a form of meeting — stepping onto that very “street” where public attention is currently strolling.

— You say that to meet, you need to go out onto the street. But today, that street often demands shock value, sensationalism. Where is the line where the attempt to “be heard” turns into a betrayal of what the author actually wants to say?

— You know, in my time, I tried my hand at what is called popular science literature, and now looking back, I ask myself: could I tackle a serious, even a very popular article now? All of it requires labor, preparation.

Meanwhile, science is moving forward so rapidly and so far that even science fiction sometimes can’t keep up. By the way, we have a contest called “Leap Over the Abyss.” It is associated with the name of the science fiction writer Sergei Aleksandrovich Snegov.

In our youth, the line between science fiction and “serious” literature was very blurred. And now — just look: the world of authors working in fantasy and science fiction is enormous. But for some reason, they exist separately from what is commonly called “literary fiction.” Although in essence — this is real literature, with deep meaning and writerly craft. Many of these authors are worthy heirs to the Strugatskys. It’s an equally vast territory, it’s just that for some reason it has been placed outside the brackets.

— Boris Nukhimovich, let’s briefly return to the internet, where it says that you donated a bronze sculpture, “Demeter,” from 1938, to the Hermann Brachert House Museum. Could you tell us how this story came about?

— Yes, it was a very sad story.

— Sad?

— Yes. I have long-standing and close ties with the Brachert Museum. I was well acquainted with its founder, Alla Semyonovna Sarul, and her husband. And Mikhail Petrovsky himself, a luminary in museum work from the Hermitage, the man who headed the department of “mechanical wonders” there – those curious clocks, solar, lunar, screaming peacocks – was our fellow countryman. He was born here, in Kaliningrad, right after the war, and he carried a special, personal feeling for this region within him. His involvement in the museum’s establishment was not just professional – it was a gift.

I remember his visit. They stayed at the “Storyteller’s House” in Svetlogorsk then, and I had the honor of accompanying them. Later, on that same trip, we were joined by the artist Valery Slomka, who was friends with Hermann Brachert himself and brought many materials for the restoration of the house-studio. In my memory, it has all merged into one bright, warm mass – the end of the nineties, a time when the museum was just coming to life.

And it turned out to be intimate, very personal, and therefore incredibly profound. But my own story with it is colored by a tragic afterglow. Vladimir Chernyaev became the director then – a journalist well-known in Kaliningrad, a man with the enthusiasm of a researcher and a childlike interest in wonder. He was burning with the idea of enriching the collection, and he was informed that the original cast of Brachert’s “Demeter” had been found in Moscow, which Vladimir later delivered to Kaliningrad. And then there followed a sequence of events where it’s impossible not to see a sinister pattern. Demeter is the goddess of fertility, of life, but in myths, she is also associated with the story of her daughter’s abduction and the cycle of death and rebirth. And so, by returning this bronze essence, possessing colossal power of image, to the world, the people who touched it channeled the discharge of that force onto themselves.

This story, of course, has become overgrown with miracles and a mystical aura. Everyone thinks it’s semi-fantasy, a literary fiction. No. Every image, every turn in that story – is the truth. Both Alexander Matveev, Petrovsky’s deputy, who appears in it as such a titan, and his wife… unfortunately, both are gone. This entire epic of the search for “Demeter” seemed to cast a long, tragic shadow. Its consequences turned out to be far greater than simply enriching the museum’s collection. It was a story about duty, memory, and the price one sometimes has to pay for an encounter with an authentic piece of the past, which, having awakened, reveals its ancient, fateful power.

— Boris Nukhimovich, you have just told a story rooted in the pre-war past of this land – the story of a German sculptor and his work. And this prompts a question about another, invisible heritage – the linguistic one. There is a widespread opinion that in Kaliningrad, due to its geographical isolation and complex history, a distinct local speech, a “Königsberg language,” has formed. Do you feel this difference?

— I think journalists sort of hype such things up. In reality, the language of the Kaliningrad region is very much a standard, averaged one. The Russian language here is quite pure, even purer than in other places.

Imagine: from 1946 onwards, people began arriving here, on this land emptied by war, under the great resettlement program. People came from all over the vast country: from Mordovia and Chuvashia, from the Pskov and Vologda regions, from the black-earth steppes. If our region had been settled only by people from Pskov, we would have the “okan’e” accent. If only by people from Vologda, there would be its own firm peculiarities. But something else happened: dozens of regional dialects, accents, intonations were mixed in one melting pot. They didn’t suppress each other but mutually neutralized, sifting out everything most distinctive and non-normative. As a result, naturally, that very pure, literary Russian language emerged, devoid of pronounced dialectal features.

Of course, over decades of isolated existence surrounded by a different linguistic environment – Polish, Lithuanian, German – some local slang words were bound to appear, but this is not a dialect, precisely lexical borrowings, most often from Polish. For instance, the word “koleyka” – a long, dense queue of trucks and cars at the border crossing. Or the phrase “What are you treating me for?” – when someone is persuading you, bargaining with you. This is the living speech of a border region, understood by everyone here.

Well, and then there are minor linguistic peculiarities, purely Kaliningrad realities. A person who hasn’t lived here simply won’t understand what it’s about. But that’s not features of the language! It is precisely in Kaliningrad that the language remains the most correct, devoid of any dialectal traits, averaged and pure.

— Then perhaps, the reflections on a “special language” are merely a superficial reflection of a deeper phenomenon, where the main question is not “how we speak,” but “about what we might not speak”? Is it possible to write something in Kaliningrad that is non-contextual, detached from the land?

— Theoretically, yes. But personally, for me, the answer is no. I am precisely a singer of the native land; everything I write is tied to biography, to local history, to a specific point on the map. For this, by the way, I am often criticized by colleagues. The prevailing viewpoint is that real literature should be universal, abstract, that there is no need to tie a story to a specific crossroads or house.

But have great literary worlds ever been born in a vacuum? There exists the concept of the “city text” — the Petersburg text, the Moscow text, the Odessa text. There are powerful regional schools, for example, the Ural poetic school, Siberian prose… although the Ural poets themselves often argue, considering this theme to be forced. I have tried more than once to urge philologists and literary historians to consider the phenomenon of a “Kaliningrad text,” but so far without result. Apparently, we have not yet amassed that critical mass that would allow us to speak of a school. There can be, of course, individual themes, like the theme of the borderland — after all, we are in it.

We, it seems, still lack that very poetic substance to confidently speak of a “Kaliningrad poetic school.” We lack bright, unique characteristics. Although certain themes do exist, of course. The same motif of transition, when one civilization replaces another. Or the feeling of limited, compressed space — that of a semi-enclave. Perhaps something could grow from that.

— If a writer today is doomed to be the voice of their place and time, then why is this voice heard so faintly against the backdrop of the past? Why is so little attention paid to contemporary authors in our society, with preference given to the classics of past centuries?

— The historical consciousness of the people – that is what is paramount. For example, Afanasy Afanasyevich Fet may seem an old-fashioned lyricist, but he exists in the cultural-historical consciousness of the people and will remain there in a hundred years.

And none of the contemporary poets will remain in that consciousness, in the direct sense. And it’s not a matter of whether a poet is good or bad. It’s a matter of the new informational structure that formed roughly at the turn of the 80s and 90s. The flows of information have changed, and now no work has time to enter consciousness because it is immediately overwritten by the next layer.

This concerns not only poetry; it concerns absolutely everything: music, cinema… even the discovery itself is becoming smaller. The Nobel Prize in Physics today is at the level of a candidate’s dissertation from the 1920s. Can you recall a single Nobel laureate from the last ten years? No. Everything gets overwritten. Information flows change so quickly that no work has time to take root.

Imagine if “Anna Karenina” were written today by some Nikolai Tolstoy. Would we see it? No. It would be lost in the general noise. Because the contemporary poet is naked and exposed before the reader – there is only the text. The reader deigns to read it, and that’s it; nothing more.

But when you pick up “Anna Karenina,” three great film adaptations immediately come to mind, mountains of criticism, Lenin’s famous phrase about the “mirror of the Russian revolution” – who the hell knows what else! A classical author appears before you in armor and full gear; their text is surrounded by a whole complex of meanings, disputes, and interpretations. This is a protective layer, built up over decades.

But a contemporary author has no such armor. Only the naked text. It’s like going out onto a football field alone against a team of eleven, where you are the goalkeeper, the defender, and the forward. Under such circumstances, it’s impossible to compete.

That’s why the last poet who still managed to wedge himself into our cultural-historical consciousness is Joseph Brodsky. Voznesensky, Yevtushenko remained largely thanks to songs. All other authors will remain within that narrow time interval that exists now. And there are very, very many of these authors. That’s the situation.

— In your opinion, who could be the Dostoevsky of the 21st century? And do we even need Dostoevskys of the 21st century?

— There cannot be a Dostoevsky in the 21st century. Let’s suppose the novel “Crime and Punishment” were written today. There are already hundreds of such novels — of the same level, with the same plot, with the same schismatic torments and language.

One cannot say that Dostoevsky’s language is flawless — critics would find something to pick at. But when he wrote, it was a penetration into a tormented soul — the discovery of a new continent, whereas now it has become a commonplace.

A contemporary writer is more likely to decide that there’s no need to dwell on the inner world of the hero: killed the old pawnbroker woman and onward, twist the plot. You can introduce conscripts, send the heroes to Capri, throw in new characters to catch the current trend. Dynamics are more important than reflection.

A contemporary Dostoevsky cannot exist not because there are no geniuses, but because there cannot be a new pioneer in a place where all the depths of the soul’s “jam” have already been explored and described. Everything that could be said about these torments — has already been said. His metaphysical insights today would be received not as a revelation, but as a smart, yet derivative stylization of the great canon.

— Boris Nukhimovich, how does one learn to read?

— I think the foundation of everything is curiosity. It’s the very engine behind both science and art. A child, a teenager, should burn with the desire to find out, “what’s there?” And in my time, reading was the primary, almost magical way to satisfy that hunger.

Take Jules Verne, for example. His books for us were a ticket to another world, where geographical discoveries became an adventure, and the laws of physics became a plot device. His science fiction nurtured imagination, a scientific worldview, and awakened interest in real knowledge.

Today, the world has changed. Curiosity hasn’t gone anywhere, but it is now satisfied differently. People read endless news feeds, short posts, absorb clip-like content – and there is also a world in that, its own information. A contemporary author must create texts that are baits for curiosity. They can be brief, but they must contain space for thought, a hint of that very depth, so that a short text does not become a dead end but turns into a door back to big books, to long, thoughtful reading, to that very Jules Verne waiting on the shelf.

How do you feel about the fact that the school literature curriculum is constantly being changed, and works that require a certain life experience and knowledge of historical context for full understanding are now being read in elementary school? This applies particularly to works of foreign literature.

— You know, I’m trying to remember now… I think we didn’t study foreign literature in school at all. We had world history, but not foreign literature. I graduated in ’73, and it’s unlikely we read “The Little Prince” or anything similar in a formal, “cultivating” sense.

But back then, we read a lot. Simply because there was nothing else, you understand? A modern teenager can’t even imagine it. You have to mentally remove the television, computer, phone, and then nothing is left but the library, the street, and the river.

Now, literature, reading, has to compete with a huge number of temptations. And these aren’t just any temptations — they are similar in their effect. Why does one read at all? To experience an emotion — that same curiosity, empathy.

But the ways to evoke emotion now are countless. And literature is losing this race in terms of accessibility and speed to modern entertainment platforms. The need for such prolonged reading is fading and will continue to fade; there’s nothing one can do about it.

It will all probably end with the poet writing, addressing poems to a specific person like a letter, like a personal conversation. Mass appeal will become impossible — only a whisper in the ear will remain.

— So it turns out we’ve come full circle again, back to where we started. Which literary genres, then, have a future? For example, does the poetic novel have one?

— The poetic novel has no future whatsoever. And forget the novel — the large poetic form itself, the poem in its epic, national understanding, has already played its part. The last true poem that reached the people undoubtedly became the poems of Tvardovsky. Not only “Vasily Tyorkin,” but also, say, “House by the Road.” Everything that came after is a descent into the tunnel of a narrow circle of connoisseurs, an experiment for the few. It’s no longer a conversation with the country, but a conversation with oneself, enlarged to the size of a book.

— Boris Nukhimovich, have your works been translated into foreign languages?

— Yes, they have been translated into German, Polish, and Lithuanian.

— What are the most interesting or non-obvious difficulties that translators have encountered?

— The main difficulty for a translator of my texts — and not only mine — lies not in the realm of accuracy or in the selection of equivalent words. It’s about transplanting images from one cultural soil into another.

In Russian culture, there exists its own centuries-old system of images, symbols, connotations. In German, Polish, English cultures — it’s entirely different. The translator’s task is not to translate a specific word, but to find, let’s say, in the German language that equivalent of emotional and cultural charge which the word carries for a Russian reader. It might be necessary to abandon direct correspondence and say it with completely different words, in a different way. Otherwise, you get an accurate but dead text, devoid of that very poetic force which lives in the subtext, in the cultural codes.

Therefore, a translator is a diplomat between whole worlds. They, by the way, have their own, separate cultural life. For now, unlike a writer, the profession of “translator” is a clear-cut specialty and a job with an entry in the employment record book.

— Boris Nukhimovich, let’s reason together about creative freedom. Where does freedom end and graphomania begin?

— It seems to me they are not related at all. A graphomaniac can be very constrained. Honestly, I would be happy to be a graphomaniac, but only if I could retain the feeling that the text is imperfect, that it needs to be worked on, that it needs editing. Because a graphomaniac in the pure sense is simply a person who loves to write uncontrollably. For whom the text “flows.” This is especially important for prose. To create such a body of work as Tolstoy’s, Dostoevsky’s, or even Sholokhov’s, it’s necessary for that internal river not to run dry.

There are writers for whom it gushes forth by nature. And there are others — for them, generating every paragraph is a Herculean labor. Such an author may never create a vast legacy in terms of volume, but that doesn’t make them worse.

It’s just that an author must either have a developed sense of style and standard from the outset, or (and this is extremely important) they must possess an internal critical faculty.

Of course, the established stereotype of a graphomaniac implies precisely the complete absence of this internal criticism, uncritical self-admiration. But I am convinced that the main thing, after all, is the flow itself. First, the text must appear. The matter. The clay. Only after that can one work with it.

If an author has innate or cultivated taste, a sense of proportion, discipline, and at the same time the text flows, then we see before us the potential of a great author. Graphomania is not a diagnosis, but the raw energy of writing. The only question is whether there is a dam of strict, intelligent selection beside that flow.

— Currently, there is a huge increase in the number of people writing. How should one view this? Rejoice at the flourishing of self-expression or worry that quality is being lost in this noise? In your opinion, can one be equally gifted in different literary genres?

— With poets, it’s even more complicated in this regard than with prose writers. A poet’s work is categorically different from a prose writer’s work. These are different universes, different types of thinking, and they often contradict each other.

Take the universal geniuses: Bunin, Nabokov, Pasternak… But even with Pasternak, prose and poetry are two different breaths, two rhythms of the heart. To avoid the temptation of comparison, it’s better to step away from these examples.

I have personal experience – I wrote a novel. And I must say: for a poet, this is violence against oneself, almost self-torment. To create it, I had to change my very working style, restructure my consciousness from a lyrical to an epic mode. For a year and a half, I didn’t write poetry. At all. My inner poet was forcibly muted to give voice to the prose writer. And only when the novel was finished and I could step away from it did a miracle of balance occur.

— Boris Nukhimovich, could you name a top-3 of spectacular literary reminiscences that can truly be considered the binding elements of world literature?

— I’m not ready to answer that question right now. I think if you dig down to the very essence, all spectacular reminiscences in world literature lead back to antiquity. Essentially, all plots were exhausted and cast into perfect form two and a half thousand years ago. Everything that happens afterwards is merely a change of scenery. The costumes, technologies, and social decor change, but beneath them lie the same tragedies, comedies, wanderings, and torments. We are only throwing new fuel onto the ancient fire – psychology, irony, narrative speed – but the flame is the same.

That’s why it seems that Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, and a contemporary author are all talking about the same thing, because they all draw from the same well of human essence. Everything has already been. Everything has already been described. Heroes don’t walk a straight line of progress – they roll like a wheel, returning to their starting points.

— If everything new is merely fuel for maintaining an ancient flame, then the library is precisely that primordial hearth where this flame has been kept alive for centuries. Why should a modern person go to a library in the era of digital noise? And how long will libraries last in their current format?

— The functions of libraries have greatly expanded, and they have expanded not towards literature: now they offer language courses and lectures on financial literacy. The library has transformed into a cultural and educational center, where the book is just one of the reasons to visit.

Look at who gathers the largest audience today. I remember at one event, the longest queue formed for Konstantin Ivlev, who published a cookbook, and not for the recognized mastodons in the field of literature. So, in the eyes of the new public, he turned out to be “the biggest writer of the year.”

The modern library is no longer a temple or an archive. It is the maître d’ of culture, who must guess and serve the guest precisely that “intellectual dish” which they crave at that moment. Be it a subtle novel, an ironic culinary treatise, or a practical seminar.

— If demand is shaped by queues for cookbooks written by famous bloggers, then what future is there for writers? The author of 2026 – what will they be like?

— The author of 2026 already exists. They will largely continue the inertia of 2025, because time has now compressed. The focus will be on prose and poetry tethered to our current wound – to the events on the line of contact, at the border, in the conflict zone. This will be the most acute, most in-demand plot. It will be the most promoted, published, and placed at the top of award lists.

And this will no longer be an author like Tolstoy, who contemplates the war with Napoleon half a century later. This will be an author-participant, a contemporary author, writing from within, while the dust has not yet settled and the wound has not healed into a scar. They will not so much analyze history as record its pulse and temperature in real-time. An instant chronicle instead of a later epic canvas.

With poetry, of course, it’s more complicated, but it too will not escape this powerful gravitational pull. The great eternal themes – a person alone with themselves, with God, with love, with death – will not disappear, of course. But in 2026, they will inevitably be refracted through the prism of that very “acute” situation. Even the most intimate lyrical plot will be read as a metaphor for the general state. And that is neither good nor bad – it is simply a given.

— Boris Nukhimovich, does a universal formula for a good text exist? And, in general, is a good text even possible?

— Of course, it’s possible. But its universal formula today is different. If we speak about language — it must be a language that pulls you along like a skein. That unwinds on its own, captivating the reader not with the force of the plot, but with its very fabric, rhythm, internal energy. Such a language is almost impossible to construct artificially — it forms naturally, becoming an extension of the author’s breath.

But the main thing is that the very architectonics of a good text has changed. A long, continuous chapter of 25 pages is doomed today. It doesn’t correspond to the rhythm of perception; it tires with its monolithic nature.

A modern good text is constructed differently: it’s a short, logically completed block that then transitions into another. Sometimes these blocks are connected, sometimes — deliberately broken. We are used to demanding linear coherence from a text, but now even that requirement has fallen away. A good text today is more of a chain of glances, a series of bright, precise frames. They can be conditionally connected by a common theme or atmosphere, or they can hold together only on the internal energy of the author’s “I,” on that very “skein” of language that permeates them. Coherence has moved inward, into the subtext, into the rhythm.

— How do you feel about the fact that some readers fall into the sin of searching for hidden messages between the lines, ignoring the very essence of the work?

— Well, that’s even good. It’s worse when an author made an effort, embedded certain meanings, and no one really sees them or wants to see them.

I have a story called “The Night of Donelaitis.” There is, in general, a great deal embedded in it. And what do those I’ve spoken with, who read this story, tell me about? “Ah, it’s about two writers traveling on New Year’s Eve, from December 31st to January 1st, in the year of the tercentenary… They travel along such and such a route, visit friends, get caught in crowds…”

That is, the pure event-driven plot. Everything that was conceived and placed between the lines remains invisible. A philologist or someone who specifically wants to delve into all of this might discern it. But such people are few.

— Boris Nukhimovich, does one need talent to become a writer or poet?

— Of course, one needs talent.

— There are so many copywriting courses nowadays that launch with the slogan: “Go and you will become a writer.”

— Go – and you won’t become one. Personally, I don’t know any geniuses. I know genius – as a phenomenon, as a standard. The genius of Pushkin.

— Why doesn’t anyone mention Mayakovsky in this context?

— Of course, Mayakovsky. There is a powerful branch: Derzhavin – Nekrasov – Mayakovsky. That line – it is ours, our own bloodline, which we all continue. And Alexander Sergeyevich [Pushkin] stands alone on his mountain. Unshakeable, but also irreplicable in his completeness. There’s no escaping that.

And what is working within this branch? It is, first and foremost, working with the perimeter, with the boundaries of what can be said with language. It is listening to that poetic hum from which the rhythmic foundation later grows. In Brodsky, for example, I clearly hear this hum in his texts. It is not a finished verse, but that primary substance, that semantic and sonic matter from which something later crystallizes.

There are people for whom this hum is distinct. It seems to me, for true poetics, this is the most important thing – not the result, but this internal hum, this pressure. This is the very sign of that “being kissed,” which distinguishes talent from craft.

— How, in your opinion, are gender differences marked in contemporary poetry?

— Differences, of course, exist. I, for example, do not read poems written by women publicly, not because I consider them worse. Beyond Akhmatova and Tsvetaeva, there are many brilliant authors — poets or poetesses, as you wish.

I sense in these texts a special feminine essence that a man cannot reproduce without falling into falsehood. Even if the poems are not of a pronounced lyrical character, this feminine essence is present in them — as a special optics, a timbre of experience, a way of speaking about the world and about oneself.

If we speak of contemporary authors, then for me in recent decades the most striking phenomenon is Masha Vatutina, a Moscow poetess. Her voice is incredibly strong, but a restless soul lives within it. And these restlessness manifest not only in poetry but in the very fabric of life, in her actions, in her public gestures. Reading (or listening to) her poems, one feels this powerful, distinctly expressed energy, shaped impeccably poetically. The most astonishing thing is that she brings into poetry the most delicate, intimate feminine experiences, topics that are excruciatingly difficult to discuss even in conversation with the closest people. And she does this with such harmony, or conversely, with such deliberate disharmony, that it becomes a confession, a true artistic act. So, if we speak of female authorship today, for me it is linked precisely to this courage of absolute expression, to the readiness to make personal pain and confusion the subject of high art, needing no gender-based concessions.

— Boris Nukhimovich, let’s try our hand at being prophets again. Could a platform like “Zen,” where content is created by algorithmic request, ultimately replace the author-creator themselves?

— About twenty-three years ago, I had such an experience… The word “blogger” wasn’t in use then, but similar text platforms already existed. Back then, the number of comments played a very big role on them.

I wrote texts of a cultural-historical, educational nature, seemingly not prone to any scandals. But no — discussions would flare up and deliberately escalate into harshness. I wrote on such a platform for about three years, then quit. There was no point in participating in these meaningless squabbles.

Although, to be fair, it must be said that back then, in 2007, all our local history was a secret sealed with seven seals: only a handful of local historians knew it. Now, anyone curious can press a button and get information — and not always truthful information.

I am myself the author of one such pseudo-history, in which, however, I sincerely believe: the death of the last great master of the Teutonic Order, Duke Albrecht of Brandenburg. This happened, I believe, on March 10, 1568. He was 78 years old at the time — a venerable age for those times. In his final years, paralyzed, he lived not in Königsberg, but in Tapiau Castle (present-day Gvardeysk). His library was also moved there.

And on that very same day, thirty kilometers from the castle, in Neuhausen (present-day Guryevsk), his second wife, Duchess Anna Maria of Brunswick, died. She was about 36. She was supposed to become regent for their son, who, due to his health, could not rule. That the duke was dying had been known for several years — it was not news. But to die on the same day?

I suggested at the time that the duchess was most likely poisoned, because in Berlin and Brandenburg, claimants were already awaiting their hour. Her death opened the path to creating a dual-centered principality — of Prussian lands and the Brandenburg Mark, which later led to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701.

You must agree, a distance of thirty kilometers is no reason to die simultaneously from the same news, which wasn’t even news. Too convenient a coincidence. The perfect opening for a pseudo-historical novel.

— Boris Nukhimovich, your works began to be published in 2004. Have any words personally changed for you over time?

— It seems to me it’s difficult to speak about specific words. A strange thing happens with vocabulary: you don’t expand it over time but, unfortunately, gradually narrow it. And if before, to express oneself powerfully, a precise, honest word was enough, now for an emotional impact within a paragraph, turns of phrase are often required that previously you wouldn’t have dared utter in polite society.

In Klaipėda, there is a symbolic monument to this process — in the main city library named after Simonaitė. On the initiative of its long-time director (who in recent years also headed the city’s writers’ organization), a “Monument to Departed Words” was installed there. It is a wall of metal plates with words that have fallen out of living use. Every year, new tiles are added to show a clear statistic of language erosion — which words we are losing. In the Russian tradition, I don’t know of such a systematic effort to record losses.

But the same thing happens with a writer: their speech imperceptibly becomes impoverished, loses its special verbal hues. They say Solzhenitsyn in his later works consciously engaged in linguistic archaeology — excavating archaic words, trying to resist the general averaging.

In dialogues, this is felt especially acutely: the speech of different characters, their internal monologues, must sound different. This is a super-task. Whether a reader, spoiled by the simplified language of media, will understand this — I don’t know. But for a writer, it is a matter of professional honor — to remember words and fight their fading, even if they are already being given monuments made of metal.

— May I ask about your creative process? Do you work with paper and pen, or is your main tool the computer?

— I work poorly. In recent years, I have, unfortunately, been very occupied with matters not directly related to art. It’s an irony: a person who, by the very logic of things, should be systematic, finds himself deprived of that system. And it turns out that for a writer, and especially for a prose writer, discipline is no less important than inspiration. One needs that very “iron ass,” to speak without euphemisms. And I have fallen out of that mode.

Now I work almost exclusively on the computer, rarely on paper. And yet, when one manages to start on paper and then transfer what’s written into digital form — that seems to be the best possible ritual. There is a necessary physicality, a slowing down in it. But, unfortunately, that happens less and less often.

There are many reasons, but the main one is the inability to isolate oneself. There is too much that one “must” do. And for serious work, one needs isolation, almost monastic. I had such an experience: I wrote my novel only thanks to the fact that I completely shut myself off from the world for several months. But now that’s impossible. There are many public events, projects, initiatives that depend on me and that I myself launched. To abandon them would mean letting people down, destroying what was begun. It turns into a trap: one cannot hide from the external world, and from oneself — even less so.

— Boris Nukhimovich, how shall we conclude the interview? With poetry or prose?

— With poetry, of course.

Preserving ourselves, defying fate,

Following Mandelstam line by line,

With the desire to endure in Russian speech,

We cannot hide in the midnight dark.

Take with you into life words in which

Resides the love of fathers and mothers’ severity.

Do not squander them in offices and on roads,

In them, the scent of apples, the sorrow of native fields.

The Russian sound in a tragic epoch

Will remain both low and high —

In ascents, in a jester’s encirclement,

In falls, profoundly alone.

Neither a foreign god, nor an officer’s saber,

Nor women’s caresses, nor sweet Madeira

Will alter the Russian core within us —

Speech has wed us into a single space.

A navigator determines the current location of a person on Earth. We’re mapping new routes in your consciousness.

Thank you!