Category: Global minds

"Truth Requires Courage". Global Confession of the Intellectual Archaeologist Vladimir Zhgursky

There are questions that always hang in the air, like dust on a deserted road. We try not to notice them until someone draws a line and asks: “But what if everything was different?” Human history is not like a book of fairy tales; it is more like a scream frozen in eternity, blood on handwritten pages, and a bitter truth that is sometimes so diligently painted over.

Where is the fine line between a tyrant and a savior? Why does truth so often end up in the shadows, while lies stand on the podium? What remains of a person when their name is erased from textbooks? Of an idea when it is anathematized? Of truth when it is ruthlessly trampled by boots? And what are we, ordinary people, to do in a world where history becomes a tool in the hands of politicians?

The guest of the anniversary issue of “The Global Technology” magazine was the intellectual archaeologist Vladimir Zhgursky, with whom we spoke about the price of a breakthrough, the loneliness of reformers, and why society vitally needs those whom it itself curses. Our conversation is an excursion into the past, an attempt to hear the echo of our own footsteps in the corridors of time, and a desperate desire to find living voices in the choir of official versions.

Perhaps, after this conversation, you will hear history differently—not as a tale about the dead, but as a warning to the living.

— Those who do not know history are forced to repeat it. Those who know history are forced to watch it repeat itself. Vladimir, what is history? As a science, as a discipline, as a phenomenon?

— I would separate these things. History as a scientific discipline is not my professional field, but as a phenomenon, as living matter – history must be inside each of us. For the sake of preserving memory: national memory, the memory of our ancestors. Because, as practice shows, those who forget their history sooner or later have their geography corrected.

— An interesting observation.

— Yes. Firstly, there are very few people who know real history. Especially today, when a countless number of pseudo-historians have proliferated. I believe they are deliberately destroying people’s minds to suit the current agenda.

Regarding knowledge of history… I believe it should come first and foremost from the family: parents are obliged to tell it to their children; if they don’t know something themselves – to point them to verified books, to reliable sources. The main thing is for children to be able to look at historical facts from different angles and see the events that transpired, and then continue to pass this knowledge on to other generations.

I think if historical knowledge, truly historical knowledge – that is, the knowledge of our ancestors – is lost, people will lose themselves completely; they will simply cease to be themselves. Moreover, in our time, enormous efforts are being made to make people forget the real, truthful history, because people who have nothing behind them, who have nothing to lean on, are easy to control. Such people become ideal members of a consumer society: ‘Be so kind as to consume and be happy. You don’t need anything else.’

I can’t even call these creatures people. They were given an illusion of freedom, like in the 90s of the last century: we were hammered with the idea – ‘now you are free.’ Free from what? It was an illusion. ‘You can get anything, any material goods.’ And you simply don’t need anything else.

Therefore, not knowing your roots, not knowing your history, is the first step towards forgetting yourself as a person. For example, now various opinions are being voiced that there were no concentration camps, that Hitler was good, that the USA, together with England and France, won the Second World War. And people are starting to believe it.

— Periodically, opinions surface that Hiroshima was not a war crime, but almost a “tragic accident” for which no one is to blame.

— As one of the United States’ rulers said: “it all happened as a result of a minor conflict.” Well, what can one say to that? There are clear markers that are now being deliberately obscured in every possible way.

And I believe the day is not far off when the inscriptions on the Reichstag, which are all in Russian, will either be painted over or the Reichstag itself will be demolished as unnecessary. Why remember history? Who’s interested in that when the winner has already been appointed? People will continue to believe that America won, while the Soviet Union just happened to be passing by during this most terrible war. This kind of attitude towards past events is the first step towards people soon unlearning how to read, then how to count, and ultimately regressing to a prehistoric period.

— Vladimir, you said that history should live within each of us. Should live, or does it live?

— It lives. I emphasize – it lives. But, unfortunately, even within individual families, very little importance is attached to history. And, frankly, it sometimes frightens me that people don’t even know their own family’s history, let alone the history of their country or their people.

History lives within each of us, but it is given so little significance that, like any unused skill, it gradually fades away.

— You speak of the “waning interest in history” – and that is a perfect transition to the topic of identity. In our era of globalization, many say that the concepts of “clan” and “national identity” are outdated. In your opinion, what defines a person’s belonging to a people today? Blood, language, culture, or something else?

— Clan is undoubtedly important, but it’s not just about blood. It matters in which society a person has put down roots, but even more important is which society they have chosen for themselves, which historical air they have decided to make their own.

One thing is to be born within an ethnicity – that is a given, like height or eye color. You can’t escape it; it’s your starting point.

But there is something far more powerful – conscious choice. When a person, not by birthright but by the call of the soul, embraces the history, customs, pain, and joy of another people: “Yes, this is mine. I accept this heritage as my own.” This is not a betrayal of blood, but an expansion of the clan, the birth of a new version of oneself through a deep, hard-won kinship.

And then, knowledge of that people’s history becomes a duty of memory. You are now their voice. You are the guardian. And this must not be forgotten.

The strength of a clan lies not in the purity of blood, but in the strength of choice and the willingness to bear the heritage. One can be born into a great culture and pass it by like someone else’s performance. Another can embrace a foreign history as their own and find a second wind.

— Is history itself more of a theoretical or a social discipline? Does it possess any kind of precision?

— No. Precision in history is completely excluded for one simple reason: history is written by the victors. Who will interpret it next and how is unknown. Most often, history becomes a hostage to political moments. Which, unfortunately, are also a part of it.

— And yet, even through this prism, we see figures who broke the very course of events. Let’s talk specifically about them. Whom would you call the main “system violators” in history?

— You know, I would add to this list not names, but actions. After all, this is a pantheon not of statues, but of breaches in a wall made of habits, fear, and dogma. I would include many inventors and military leaders—all those who truly made a huge contribution to humanity. Among them would be the unknown Chinese who first mixed saltpeter with coal, and the admiral who gave an order leading to certain death, but it was this order that saved the squadron.

The strength of reformers, upstarts, and all rebels lies not in genius, but in the willingness to step over the line, to where all maps and instructions end. The system always says, “It can’t be done this way,” and at some point, they decide to test that, and it turns out it can be done, and then it turns out the world can no longer live the old way.

Therefore, into this pantheon, I would induct not heroes, but points of no return. Moments when one person looked at the rules and said, “I will try to act differently.”

— By the way, if we are talking about certain historical events that for some reason are now commonly viewed ambiguously… There is an opinion that Stalin was “deceived” before the war. What would you say to that?

— You know, I am not a historian to give definitive assessments. But, based on known facts, I can state my opinion.

The assertion that Stalin was “deceived” is incorrect. He was not deceived; he miscalculated—that is a significant difference. Yes, he did receive warnings from allies, from his own intelligence agents, and even from German defectors. The facts confirm this. But something else is important here. His main task as commander-in-chief at that time was to delay. He saw that the country was not ready for a major war and tried with all his might to buy time. The pact with Germany was part of this strategy—an attempt to postpone the inevitable at any cost. A cost that turned out to be monstrous.

And here I must make an important clarification that many today deliberately erase. The Great Patriotic War and the Second World War are not the same thing.

The Second World War began in 1939, when the USSR was not yet a participant. The Great Patriotic War is our national tragedy and feat, which began for us on June 22, 1941. To confuse these concepts is to devalue both the specifics of our history and to forget the monstrous price paid specifically by our people.

So, returning to your question… Yes, there were warnings. But the task was not to “believe” or “not believe” them. The task was to prevent the war from starting now. And herein lies the tragedy and terrible responsibility of those decisions.

— If we are talking about people who went against the system, could Joseph Stalin be called such a person?

— In a way — yes. I would put it this way: he, or more precisely, his team, often acted paradoxically. Because a single person, as a rule, decides nothing — it was precisely a team, a collective mind trained to think in terms of total war and absolute resistance. The Germans, having rolled like a steamroller across Europe, encountered not just another army; they encountered a different physical reality. The Germans knew what awaited them at the gates of the next state, but with the Soviet Union, everything went wrong — from the very beginning, their precise system failed.

Their calculated blitzkrieg, their tactical algorithms — all of it failed from the very first day because the main principle did not work: after the first crushing blow, the enemy was supposed to break. But here, they did not break; on the contrary, a kind of leaden, inhuman fury was born in response, rendering all their military textbooks fit for the trash.

Take the Brest Fortress, for example: the Germans did not expect to get bogged down there for long; they thought they would pass through quickly and move on. But no, the fortress drew enormous enemy forces onto itself, pinned them down, and this seriously affected the entire further advance. The fortress became a bone in their throat, immobilizing entire divisions that were supposed to be racing toward Moscow. And how many more such examples were there?

Therefore, yes, Stalin can be called a ruler who acted differently than was customary. In places, his methods might be considered wrong, but it later turned out that precisely these seemingly erroneous actions led to a positive outcome. He created a machine that won by breaking all the rules of victory, a machine that did not retreat even when it was logical, that did not surrender when it was inevitable, that fought even after death.

Stalin brought his own, new, cruel, and unconditional rules, according to which victory has no price, and the whole world accepted this. So yes, I can say that Joseph Stalin was a man who went against the system.

— You are describing the triumph of an individual who changed the course of history. But are there cases where a system is successfully challenged not by one person, but by an entire group?

— Any group that begins to change something, to make adjustments to life, always starts with one person. If this person manages to find compelling arguments, if they have an idea capable of captivating others, and they can explain why their path leads to a result—then followers will appear. But the spark always comes from a single leader who decides to go against the established system.

Imagine a completely traditional society. The person who first tied a stone to a stick and created an axe—was already the first to deviate from the norm. It is precisely such people who have changed history; it is they who create something.

A person who is perfectly integrated into the system is a flawless executor, but they cannot create anything. This is neither good nor bad; it’s simply that everyone has their own tasks.

— Are there vivid examples in history of such “unfinished rebellions” or “incompletely realized ideas”?

— I would put it differently. Most often, the undertaking was brought to completion, but it went in a different direction than originally intended. There are masses of such examples.

The most interesting thing happens when it’s not a technology that goes “astray,” but an entire idea, a whole social movement. A vivid example that comes to mind is, of course, Germany’s path after the First World War. The initial impulse, if you think about it, was even noble: to restore the nation’s desecrated honor, to return its dignity. But what did it end with? That very period in ’45, known to the entire world. The idea of national revenge, falling on the fertile soil of humiliation and crisis, mutated into something monstrous.

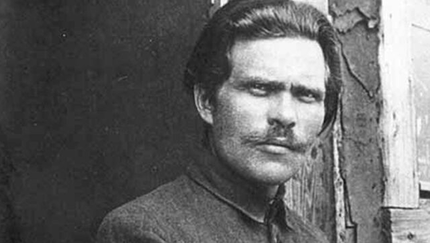

Or another, less bloody but no less telling example—Nestor Makhno. He dreamed of a society of absolute free will, without money, without state governance, based purely on self-governance. A beautiful idea in theory, but it stalled, encountering harsh objective reality and, importantly, the human factor.

And here we approach the main law that explains why so many undertakings go awry: any idea, once it gains more than two or three followers, inevitably begins to fragment. Each new adherent sees flaws and decides: “No, I understand our common goal better; I will make it more perfect.” The clearest example is the fragmentation of great religions. Christianity, Islam—despite all the unity of their original sources and symbols—split into movements that have spilled rivers of blood over centuries arguing with each other.

So, most often, the issue isn’t that the idea was bad or that it couldn’t be brought to completion. The issue is that, upon entering the complex world composed of millions of human interests and interpretations, the brightest idea begins to live its own life, and its final portrait often turns out to be a caricature of the initial sketch. This is the main paradox of history: we try to build the future, but the material for it is the unpredictable, changeable human present.

— It’s good that you brought this up. If even the greatest teachings fragment, then what does that make the Bible? Can it be considered a historical document?

My personal position is this: it is a work undoubtedly worthy of study. Whether to believe it or not is a personal choice for everyone, but the Bible contains many skillfully articulated thoughts.

Unfortunately, political influences were also involved. Given how many times it was rewritten, there are significant doubts that it has reached us in its original form: too many layers, too many edits…

— But still, can the Bible be considered a historical document in the strict sense?

— No, I would not view it as such. As a historical source, it contains too many inconsistencies and chronological overlaps. If you start carefully analyzing the described events from the perspective of geography, dating, and logistics, many questions arise. The events likely occurred, but they are presented through the lens of faith and tradition.

The essence of the Bible, in my opinion, is not in recording historical facts. It is about something else. What is that? Everyone will find their own answer when they read it. And the most remarkable thing is that each of these answers will be correct in its own way.

So, as a historical document, the Bible can hardly be considered. I wouldn’t claim this with absolute certainty, but I lean toward this view. As a great book that shaped minds and civilizations—undoubtedly.

— If the Bible shaped minds by providing a certain frame of reference, then it’s logical to ask: does society need those who constantly unsettle this system? Can we say that society always needs rebels?

— Unquestionably. Rebels, reformers, people who challenge the system are vitally necessary for any society in any country. Otherwise, there simply is no movement. If everyone lives strictly by prescribed rules, development will stop, and society will stagnate at the level at which those rules were written.

Yes, such people are often rejected, persecuted, they remain misunderstood, sometimes they are even physically eliminated. But a moment comes when their correctness is confirmed. This is precisely how they change history; this is precisely how they change the world.

— You’ve touched upon an important idea: history often refrains from delivering unequivocal verdicts. Let’s take a specific, very painful example — the figure of submariner Alexander Marinesko. For some, he is a hero who carried out the “attack of the century,” for others — a “killer” who sent thousands of people to the bottom. In your opinion, is it even possible to pass some single, fair judgment on him? Or are we doomed to an eternal confrontation between these two truths?

— You have chosen a perfect example that exposes the very essence of the problem. Marinesko is a crack in our perception of history. Yes, if viewed with a dry, detached eye, both definitions — “savior” and “killer” — are legally justifiable. For a Soviet soldier at the front, he was a savior who drew upon himself terrible enemy forces. For a German youth perishing in the icy water — a merciless killer. And both these truths are genuine, both are earned through suffering.

But here we must make a crucial distinction — between tactics and strategy. War is not a duel governed by rules of honor. It is a giant strategic machine where the very existence of peoples is at stake. And in this machine, figures like Marinesko are tactical instruments of monstrous power. His attack was precisely that kind of harsh, unequivocal tactical move which served our common strategic goal — victory, the price of which we know.

Therefore, I am convinced: the very framing of the question “is he a hero or a killer?” in relation to a soldier acting under conditions of total war is incorrect. It is an attempt to dress trench truth in a civilian frock coat. He was neither one nor the other in their pure form. He was a function of the monstrous reality in which all of humanity found itself. He was a soldier and acted as the situation demanded at that time. And his personal tragedy, as well as his glory, lies in the fact that he performed this function with maximum efficiency, however terrible it may have been. To judge him from the standpoint of peacetime is like judging a sapper for clearing a minefield instead of growing wheat on it. His task was different — and he accomplished it.

— You speak of responsibility within the framework of a military task. But what about the responsibility of those who themselves define such tasks for entire peoples? Lenin, in essence, took upon himself responsibility not merely for a battlefield, but for the restructuring of an entire country.

— If a person takes upon themselves the responsibility for large-scale changes, they must be prepared for the consequences. This rule is universal.

Regarding a figure like Lenin, under the current laws of the Russian Federation, he would likely fall under articles related to extremism and terrorism. It is enough to recall the story of his brother, Alexander, who attempted to assassinate the Tsar.

Before changing the world, a person must understand the measure of their responsibility. But every person is inherently weak and cannot foresee everything, which is why matters often exceed their initial framework.

At a certain point, their idea and actions begin to live a life of their own, and they lose control over them. This is, perhaps, the main paradox of any revolution.

— Vladimir, you’ve told so many stories about those who broke the rules. Whose story of fighting the system resonates with you the most? Whose motives and inner struggle seem to you the most powerful or tragic?

— If you survey the whole of human history, there turn out to be a great many such system-crackers. But what has always struck me is the unconventional thinking of great military commanders. That very ability to act paradoxically, when your main trump card is not the sword, but an understanding of human nature.

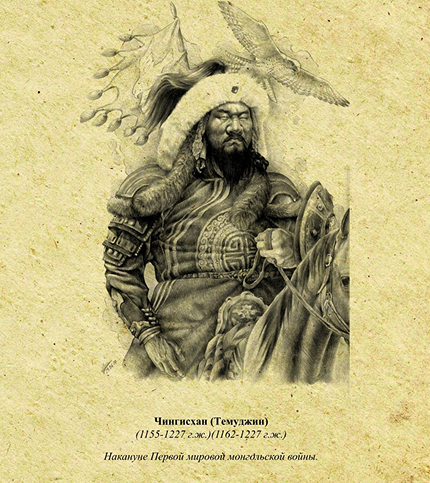

Take, for example, Temujin Genghis Khan. He knew perfectly well that all Mongols, all those fearless warriors, were terrified of thunderstorms. In their beliefs, thunder was the voice of the god Sulde, so as soon as the sky split with the first clap, the entire horde, all the invincible horsemen, would dismount and fall to their knees, trying to appease the deity.

Genghis Khan, being a Mongol himself, lived by these same beliefs, but unlike others, he decided not to submit to fear, but to use it. Anyone else in his place would have continued to pray, but a genius always sees an opportunity where an ordinary person sees only a prohibition. Genghis Khan did not fight the superstition; he took charge of it and turned collective fear into a weapon of mass destruction.

He began to time his key battles to coincide with the onset of a thunderstorm. And imagine the horror of the enemy: a avalanche of horsemen is charging, and at that very moment the heavens unleash their roar and fire upon you! The enemy saw that the gods themselves were fighting on the side of the Mongols, and the will to resist was broken in an instant. Battles effectively ended before they began—without unnecessary bloodshed. Now that is the highest class! Genghis Khan did not go against the system of beliefs; he used its very architecture to build his empire. That is what it means to think in paradoxes: not to break down a wall with your forehead, but to find a hidden door that had been there all along.

— That’s brilliant! But how did he manage to time the thunderstorms in practice? Even today, with our technology, accurate weather forecasting is a complex task.

— In those days, people were much closer to nature. By looking at the horizon in the evening, they could already know what the morning would bring. They took everything into account: the color of the sky, the direction of the wind, the smell and temperature of the earth and water. These weren’t instrument readings, but sensations. Back then, it was a matter of survival.

Unfortunately, over time, people have lost this connection. On the one hand, relying on instruments is convenient, but on the other hand, most of us no longer know how to see the universal mechanism in natural phenomena. And yet, all natural signs are part of a system that nature itself has been building for millennia. People observed it attentively and built their predictions.

Genghis Khan was precisely that—an incredibly observant man. Today, one might say he had a technical mindset. His closeness to nature and his powers of observation helped him become a great commander.

— And yet, the ability to “read the signs” was once the property of entire nations, accumulated over centuries in omens and proverbs.

— However, originally, many of them had a completely different meaning. For example, the superstition “you cannot give a knife as a gift” has its roots in pre-Christian Rus. Back then, there were no locks on the doors of houses where people lived—that was a later European innovation. In the evening, a family would sit down for dinner, and if the head of the family had seriously wronged someone—for instance, had caused harm to another family—the offended person could enter the house and plunge his knife into the center of the table.

This was an act of declaring enmity, a kind of declaration of a blood feud. This is precisely why knives were not left on the table overnight, and why they could not be given as a gift—such a present was equated to a declaration of war.

But it’s important to understand: the majority of omens—about 75 percent—were simply far-fetched. If something didn’t work out for someone just once, they immediately elevated it to a rule. And then, as the old proverb says, “every piece of gossip grows by the length of the tongue that tells it.” The more tongues it passes through, the more distorted it becomes.

So my attitude towards omens is simple: if you shouldn’t wear something because it’s uncomfortable, dangerous, or harmful—then yes, that’s a real “should not.” Everything else is most often just a superstition that has lost its original meaning.

— You have touched upon a very painful topic. Did history itself often reward such people in a timely manner and according to their merits? Or is recognition almost always a posthumous mask, replaced during their lifetime by the thorns of persecution and envy?

— Alas, the scales almost always tip towards the latter: during their lifetime, such people are rarely celebrated. More often, their fate is to be exiled, misunderstood, or to have their discoveries appropriated by others. Around a true innovator, clever “hangers-on” always swarm—those who know how to seize the moment and brilliantly sell someone else’s idea while its creator remains in the shadows.

Recall Christopher Columbus—he discovered a new continent but died in poverty and obscurity, while Amerigo Vespucci successfully “intercepted” the glory, giving the land his name. It is an eternal law: those who can do, rarely know how to sell. And vice versa. To combine both gifts is the lot of a very few.

And this brings us to another tragic paradox of leadership.

It also happens that a leader who has made a breakthrough and raised people up eventually steps back. He looks at the movement he created and realizes in horror: “This is not what I wanted. This is not the reality I had in mind.” But he no longer has the strength to change anything, to prove anything; he simply burns out, leaving behind only a bright but short-lived flash.

And at that very moment, his “banner” is picked up by those who consider themselves the new prophets. No one consults the original leader anymore. It is at this point that the great schism occurs—new movements, sects, and ideological offshoots are born. Thus, the fire of the pioneer turns into the dogma of his followers.

— So, are winners really not judged?

— History shows that yes—winners are indeed not judged. It is part of human nature: if you won, it means you were right. Whether this is truly the case, time will tell. But I cannot say this is always correct, because those who are right do not always win.

And after a victory, the rewriting of history absolutely always begins. Unfortunately, there is no escaping this—such is the practice.

— You analyze the motives and consequences of the actions of great “system-breakers.” But in your opinion, what is the main trap that any ruler or leader falls into?

— At the heart of it all lies a great paradox: if you want people to stop believing you—always tell nothing but the truth. If you want people to look for a hidden meaning in your words—be utterly direct and open. Human nature is such that they always need to pry, to dig something up. And the “truth” they uncover will have very little to do with reality.

Take Stalin, for example, and his cruel methods. But what do we truly know? The country rose from its knees. It won the most terrible war in history. The main tasks of the era were accomplished. By what means? Folks, it was a different time. He himself spoke of “excesses,” but these were excesses at the local level. A strange myth has emerged, as if Stalin personally led everyone by the ear to prison. No! A gigantic apparatus was at work. And any apparatus contains everything: mistakes, careerism, score-settling. This is the eternal price of any large-scale action.

But! Here is the biggest “BUT”!

Just 20 years after a war that should have thrown us back to the Stone Age—a human being flew into space.

That ends the discussion. Victory. Space. These are facts. They are ironclad. To argue with these facts is to deny reality itself. History delivers its verdict based on the mark left through the ages, and this mark remains forever.

— You’ve mentioned cruel methods and their justification. This leads us to the main question: where is the line that separates a reformer, who breaks the system for the greater good, from a tyrant?

— And that line is actually simple. It is all determined by motive. A tyrant acts for himself—to satisfy his own ego, his thirst for power. A reformer acts, even by harsh methods, for the sake of an idea, to bring real benefit.

For example, there was a historical figure—Vlad Țepeș, Vlad the Impaler. Yes, he came to power through violence. Yes, he built his vertical of power on fear. But here is what is important: a generation later, the people who grew up under him outgrew that fear. Those cruel punishments lost their relevance because the very system he had forged became the new reality. Not to steal, to work conscientiously, to defend one’s land—this became the norm, an internal need. And fear as a tool simply ceased to be necessary.

He is called a tyrant. But ask yourself this: how many tyrants do you know who were excommunicated from the church because they sacrificed their personal interests for the prosperity of their country?

That is the entire answer. A tyrant is guided by personal interest. A reformer, even the most severe one, is guided by the interest of the people. One builds a palace for himself, the other—a fortress for everyone. And history, sooner or later, delivers its verdict based on the results of that construction.

— Let us examine this mythological whirlwind that swirls around real historical figures. Why were the images of personalities like Vlad Țepeș deliberately turned into monsters—vampires, the living dead? What is behind this demonization?

— Yes, Vlad Țepeș has been labeled a vampire, a monster. But in reality, he is an absolutely real, concrete historical figure who is still considered a national hero in Romania itself!

So what happened back then? He stirred up the entire comfortable and convenient system that had been established by the ruling elite. A system in which the boyars profitably collaborated with the Turkish Sultan, and the Orthodox Church took a passive position. In this system, no one thought about the common people.

And he came and declared: “No, this will not continue. We have our own country, our own language, our own national self-sufficiency, and we will fight for it.” This made many people at the top very uncomfortable. And from this arose the fairy tales that he was a vampire, that he ate children. The man was slandered because he was a true patriot of his people, not a Turkish lackey. And the most terrible thing is that the story of Vlad Țepeș is not unique. It repeats itself with frightening regularity.

Take recent history. Muammar Gaddafi—under him, Libya was one of the wealthiest countries in Africa. He dared to announce the abandonment of the dollar and a transition to the gold dinar. The result? He was destroyed.

Saddam Hussein—he was instantly re-branded as a terrorist. He asked before his execution: “I am a soldier, at least have me shot.” But they hanged him. He was not just executed—he was humiliated.

Why? Because all of them, each in their own era, challenged the ruling global elite and its dominance. They were slandered, declared terrorists and monsters, because they interfered with the “convenient” system built not in the interests of their peoples.

So, the line between a national hero and a “bloodsucker” is often drawn not by history, but by political expediency. And he who is a demon today may turn out to be a visionary tomorrow, and vice versa.

— We have spoken about the cost on a historical scale—blood, wars, broken destinies. But what is the personal, human cost for the one who goes against the system? How did their life unfold beyond triumphs and defeats?

— The price for any absolute idea, for any step outside the system, is almost always loneliness. You are received everywhere, people shake your hand, present you with awards. But when you are left alone with yourself, you understand: these very people who just clapped you on the shoulder are saying behind your back: “No, he’s a psychopath. I don’t want that kind of ‘happiness’. Let it be him, but not me.” Even if he succeeds, let it be without my participation.

This is the ultimate price. A lack of understanding at the very moment when it hurts the most. And when the truth is revealed to everyone, and your correctness is recognized—unfortunately, it is often too late. You are no longer alive to see it.

And, of course, one cannot fail to notice those who affect this very “misunderstood” and “significant” persona without having truly created anything. These speculators in loneliness have always existed and always will. But for the genuine pioneer, for the one who truly shatters stereotypes, the price is not posturing, but authentic, profound loneliness. The loneliness of a person who has seen the land, while everyone else is still clinging to the wreckage of the ship by the familiar shore.

— There is a question I absolutely adore asking: “If you had the opportunity to meet any historical figure, who would it be? And what single question would you ask that person?”

— You know, when I hear someone speculate, “I would have acted differently in his place,” I always have the same response. I retort: “Then go and do it! Who’s stopping you?” The thing about these historical figures—both the positive and the negative ones—is that they acted. They did things. That is the difference.

As for whom I would like to speak with… Naturally, with Genghis Khan. Naturally, with Yaroslav the Wise—and not without reason does he bear that name. His reign was an entire epoch of reforms and events. Of course, I would take immense pleasure in speaking with Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov—that is beyond dispute. And, naturally, with Nestor Ivanovich Makhno—I find him a very interesting personality, his way of thinking and the goals he set for himself are deeply intriguing.

From foreign figures… Perhaps only Genghis Khan. The others don’t quite captivate me. But this, I emphasize again, is my personal opinion, which I impose on no one.

However, with Dracula, for example, I have no desire to converse. He is an interesting personality, the events during his life were vivid, but for me, everything there is more or less clear. There is no real ambiguity. It was clear: the man was a patriot of his country, he placed its interests above all else. And why he acted so harshly is also perfectly clear.

Many rulers tried to act softly and carefully, to avoid the dirty work and remain “pure and pristine” in history. But, for example, Ivan the Terrible, Joseph Stalin—these are people who took responsibility upon themselves. They acted harshly, but we are now looking at the results of their actions. It is with them that one wants to speak—with those who bore that burden and saw a horizon invisible to others.

— When we speak of history’s secrets, it’s always interesting: does a great deal of truly classified information exist? Or do the main secrets lie not in special archives, but in the shadow of our indifference?

— You know, there are certainly enough classified materials. But I would draw attention to another, no less important category. In the archives of the entire world, including our own, there are documents that are formally not classified, yet they have not been made public. Why? Under the pretext of being “unrequested.”

It’s difficult to give an example off the top of my head, but I recalled one, a very telling one. Everyone knows about the heroic deeds of anti-tank dogs that threw themselves under tanks. That is a heroic, but well-known chapter.

But how many have heard of an entire combat unit of attack dogs? I’m not talking about mines on their backs, but about real attacks. These dogs engaged in close combat; they were trained to seize and tear apart the enemy. They accounted for an immense number of enemy soldiers killed.

And when the war ended, this entire unit was destroyed. The reason is monstrous in its logic: these animals could not be demobilized because they were weapons aimed at humans and could not return to a peaceful life.

So, here is a historical fact for you. It is not stamped “Top Secret.” But you will hardly find it in textbooks. Why? This fact is considered unimportant. Although, in reality, it is very important because such facts tell us about the price of victory, about its darkest and most inconvenient pages that do not fit into the official, celebratory myth.

I have given only one example. But there are many, many more such stories—unclassified, yet forgotten. And sometimes they tell us more about the past than all the declassified documents put together.

— You mentioned classified archival documents. If we take examples from the recent past that shook the world—like Chernobyl—what do we truly know about such catastrophes?

— Chernobyl. Undoubtedly, much there remains classified to this day, and the true causes are known only to a very narrow circle. This is natural—who would tell everything as it happened? But, as a rule, after 50-70 years, the archives are opened. And here we encounter the central paradox of such tragedies.

The Chernobyl catastrophe was a monstrous lesson that made all subsequent nuclear power plants in the world much safer. The price of thousands of lives and contaminated lands is the knowledge that now protects millions. But if we are to “add more to this same cup”… we must approach the darkest and ethically unbearable side of progress.

Many breakthroughs in medicine, especially in the fields of anatomy, pharmacology, and the impact of extreme conditions on the human body, were obtained thanks to the “research” of scientists from Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and the particularly notorious Japanese Unit 731.

There is no need to elaborate in detail on what that unit was. They conducted inhuman experiments to create bacteriological and chemical weapons: people were frozen alive, burned, infected with deadly diseases, and then coldly, scientifically observed to see how long a person could survive.

And here is a staggering, conscience-shocking fact: thanks to the knowledge they acquired, medicine took a significant step forward. This sounds terrible and cynical, but to deny it is to close one’s eyes to one of the darkest pages in the history of science.

Moreover, some of those who served in that same Unit 731, after the war, calmly taught at universities, and their “developments” were assimilated into global science. There it is—the most terrible price of knowledge: sometimes it grows from soil drenched in blood and inhumanity, and we are forced to live with this legacy.

— But where, then, is an ordinary person, without access to secret offices, supposed to search for that very truth? Where are these facts?

— The truth often lies not in classified reports, but in places that are open to anyone. A vast number of facts are stored in archives—be it the Podolsk archive or any others around the world. Many documents do not bear a “secret” classification; they are simply “unrequested.”

The algorithm is extremely simple. You hear about some historical fact—your path leads to the archive. If an event truly happened, it inevitably left a trace in the documents. And if they are not classified, they are obliged to provide them to you.

But the main obstacle is not even access, but our consciousness. The old principle kicks in: “If you want people to stop believing you, tell them the truth.” People are often more interested in conspiracy theories: “Oh, I read on a secret forum…”, “They lie on television, but this secret knowledge…”. No, comrades! It’s all much simpler and more prosaic.

If you are a contemporary of events, the best source is the place where they are happening. Are they telling you about Ukraine? Go there. Interested in the Middle East? You are welcome to go there. The truth requires courage: it can be cruel and inconvenient, but it will be the truth. And the main rule is to hear both sides. The truth is usually born not in headquarters, but at the “grassroots” level, among the people who have become hostages of circumstances.

If the events are long past, your path leads again to the archive. But not to the internet—to the paper, dated documents with official stamps.

Let me give you a simple example. Take the Great Medical Encyclopedia published before 1961. There, in black and white, it is written: “Alcohol is a narcotic.” After Nikita Khrushchev began the popularization of “cultural drinking,” this wording was removed. There you have it—a documented fact.

Therefore, take yourself and carry yourself to those yellowed pages. The truth is found there. Everything else is a reconstruction, which can be fantasy.

That is the entire secret. People who do not know history are doomed to repeat it. And those who do know are doomed to watch as others repeat it. Our task, yours and mine, is to choose which one to be.

— What is it that everyone who knows history would not want to repeat? What would one wish to avoid?

— One would wish to avoid untimely measures and procrastination. We, unfortunately, have this national trait: we take a decisive step forward only after a powerful kick from behind. Only when we are truly cornered—only then do we begin to act.

It is this moment—this forced delay—that one would wish to avoid. And then… Then time will tell who was right and who was wrong. As for the events that are happening now… One must win. One simply must win. And that is all.

— Vladimir, as it happens, you have become the guest of our magazine’s anniversary issue; it is turning exactly two years old. In connection with this small milestone, what would you, as a person who deeply feels the flow of time, wish for our magazine on its further path towards new anniversaries?

— I would like to request, if it is possible, a small, brief interview in the magazine’s 20th-anniversary issue. And let that interview be about something simple, something human.

— Very well, I promise you that. Yes.

— Thank you very much.

We’ve discovered new laws of the Universe in your pocket. By the way, there are many forgotten things in the Universe too.

Thank you!