Category: Global minds

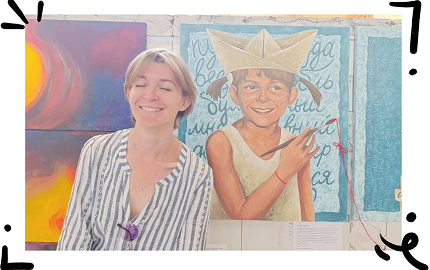

Interview with artist Daria Lyulyukova

In an era where discussions about the future increasingly boil down to algorithms, silicon chips, and Martian colonies, we are searching for those points of support that remain exclusively human. What will become of the experience that cannot be digitized? The feeling of rough paper under your fingers, the chance coincidence that turns into friendship, the ability to draw a connection between life experience and a line in a portrait?

We invited artist Darya Lyulyukova to talk about a future that has a smell, weight, and a heartbeat—an author whose work is a visual manifesto in defense of human feeling. Her works are assembled from old books, corrugated cardboard, and imbued with the history of materials. Her artistic method is a response to the challenges of our time, where the value of manual labor and personal experience is paramount.

In this interview, we reflected on why tactility could become a new language of communication, about a future being created in the artist’s studio, and about the most brilliant scenarios that life itself writes.

— Dasha, thank you for agreeing to the interview. In your perception, has the future already arrived, or is it yet to come?

— Relative to yesterday — yes, it has undoubtedly arrived.

Actually, that’s a brilliant question. The future arrives selectively: for those who dreamed of always being able to communicate with anyone remotely and without problems, the future has been here for a long time. In our reality, what was once the future is now simply a given, because reality exists here and now.

If we speak philosophically, then for me, the future is always ‘tomorrow.’ And today is just a moment, a thin line between the past and what will be tomorrow.

— And in general, does the future frighten or intrigue you more?

— Definitely intrigues me. I’m insanely curious about what tomorrow holds, although right now I’m learning the great art of living today. Recently, I went on a big month-long trip to the south, and circumstances plunged me into conditions where you have to trust life itself. In the end, everything turned out surprisingly comfortable, and this experience became the best lesson for me: when you let go of control and live in the present, the future adjusts itself to you.

— Okay, then let’s talk about the present. Have you ever had a feeling that creativity helps to overcome some kind of distance, not necessarily a geographical one? Maybe the distance between a dream and reality, or between you and a person who seemed unattainable?

— Thank you for that question. Well, it all started for me with a simple need to draw people. If you trace the chronology, and I, by the way, as a prepared artist, have it neatly saved on my phone, you can see that it started with musicians, drawn from life or from photographs. I immersed myself in portraits for a year and a half, and at some point I decided I’d had enough of large series, I would paint one piece at a time in a unified style.

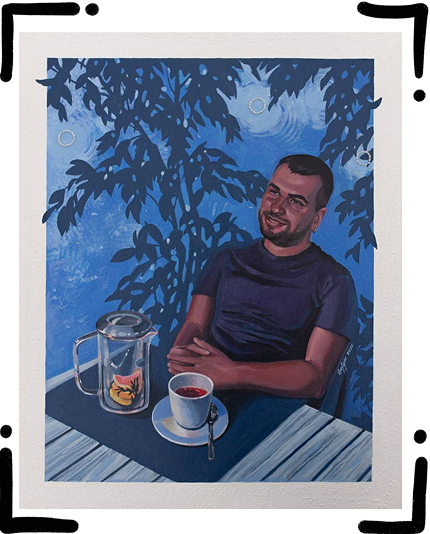

The subjects of these portraits became family, friends, and musicians. Perhaps you know the band “Sedmaya Rasa”? I had a dream to draw from life those I listen to and love. I remember being 15 and replaying this band’s albums, and years later, at one of their acoustic concerts, I passed Sasha, the band’s leader, a note with the question: “Alexander, would you pose for me?”. And he agreed! He sat in the studio for six hours, and that’s a real feat.

— What thoughts were going through your head at that moment?

— At that moment, I was telling myself: “Dasha, just don’t ruin everything!”. Now, when we find ourselves in the same city, he comes to my exhibitions, and I go to his concerts. Once he even brought a member of the band “Epidemiya” to the vernissage. The people at the exhibition that day couldn’t believe their eyes, because for our provincial town, such connections are something incredible.

Also, in this series of works, there are portraits of my very different grandmothers.

— Then I have a question for you, as a portrait artist: how do you ensure that art doesn’t become simply “extracting beauty from someone else’s pain,” but remains a respectful act?

— I had always mostly drawn people of Caucasian descent, so even my Asians ended up looking like Europeans, and then I wanted to learn to convey human diversity. So a project was born consisting of 17 portraits of people of different nationalities. I looked for faces on National Geographic, and behind each portrait was a real story. My task was to draw the portrait and engage the viewer, to tell that person’s story. For example, the story of an albino girl from Papua New Guinea. For me, it was also a matter of anatomical interest and a deep immersion into a tragic context. I was shocked to learn that in Papua, albinos are treated as ritual animals, they are often killed for talismans, and they rarely live to be 18 years old. I painted a portrait of such a girl in a calico dress, with a ripe mango in her hands, and with a sense of the fragility and injustice of that life. This is a whole story that I, as an artist, cannot help but immerse myself in.

— Was there a work of yours that was born unexpectedly?

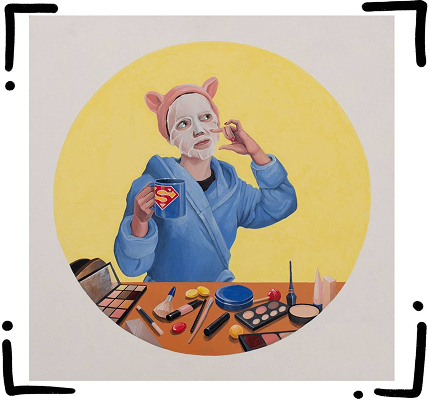

— Once, a competition was announced in Moscow called “Without Right Angles.” This was during the COVID times, when we were sitting at home. I had three canvases, 20 centimeters in diameter, lying around, and I thought, “why not put them to use,” but I didn’t know what to paint on them.

And one night, it hit me: “I need to paint chickens!”. Why chickens? I still don’t understand it myself, but nevertheless, I painted a whole family of hens, roosters, and chicks. And for complete absurdity, I framed each piece in a half of an eggshell. With that work, I won second place in that competition!

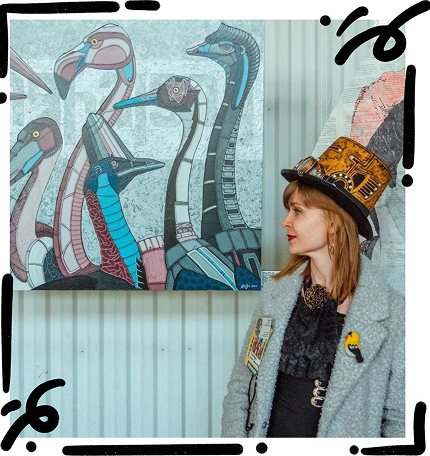

After that, I decided to create a proper barnyard: so turkeys were added to the chickens — a dad, a mom, and children. These are no longer just paintings, but tactile stories for every viewer.

My technique is special: I draw and glue, then draw and glue again. I use everything: corrugated cardboard, twine… But the main material is old, unwanted books and magazines. I roll pages into tubes and assemble the paintings from them. Sometimes, while rolling, I read what’s written there. I remember coming across some moldy educational magazines. I think: well, they have to go somewhere, better they go into art than just go to waste.

— What material is the most difficult for you to work with?

— The most difficult material for me is oil paint. It’s great on its own, of course, but personally, I have a complex, almost toxic relationship with it: it smells, takes a long time to dry, requires caustic thinners, it’s a harsh material. With acrylic, for example, everything is simpler. That’s why I started experimenting with other materials.

— And so your tactile project began?

— Yes, I create canvases with different textures, with perforations, with details: I stitch some things, I glue others. Now this has grown into the foundation of my current creative work.

The greatest pleasure for me is to give the viewer the opportunity to break the main museum rule: ‘do not touch with your hands.’ How can you not touch when you want to! My works can and should be stroked; that’s what all these little stitches and three-dimensional elements are for.

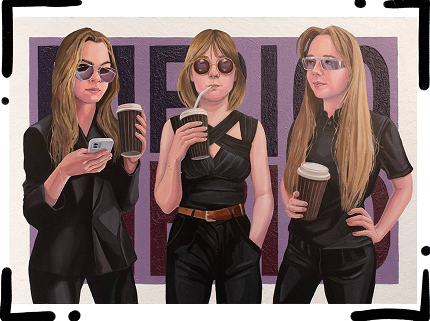

Later, I transferred this tactile approach to portraits. For example, I had a ‘tea-and-coffee’ project about domestic intimacy, where I depicted people with a cup of tea, and in the background were their personal belongings – special mugs, teapots. I added my own tactile detail to each portrait: little stars that glint differently, or a texture related to the person’s habits.

And there was also an interactive element in this series: I drew cakes and asked the viewers to guess their names. It was so wonderful! I immersed myself in the history of desserts then: I learned about the Viennese Sachertorte, which two confectioneries still argue over, and the German ‘Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte.’ I tried almost all these cakes for inspiration. Even simple candies in the paintings look so real you want to eat them. It’s a whole world that you want not only to see but also to feel with your fingers, and sometimes, even with your tongue.

— This is an amazing and even necessary discovery, because we are increasingly living in a ‘contactless’ world. Don’t you think the future threatens us with the loss of some fundamental, physical experiences that are important for creativity and for life in general?

— Everyone talks about a future with robot waiters and virtual worlds, but I think about something else: about the sound of the crowd’s hum, the monotonous buzzing of a large number of people. What will happen if it disappears? If everyone is locked in their own digital box?

But the most important thing is tactility—the finest work of nerve endings on the fingertips. If you play a musical instrument, you can change the angle of your finger, and the sound will immediately change. Artificial intelligence is incapable of such subtlety because it’s a different level of being.

In acupuncture, to find the right point, you must first feel it on your own body, not blindly follow a diagram. This is knowledge that cannot be transmitted by an algorithm because it requires human presence, the human capacity to feel.

The true art of the future, and my personal future, is not complexity for the sake of complexity, but depth of feeling. The ability to draw a connection between the flap of a butterfly’s wing and a hurricane on the other side of the world.

Art is precisely the search for such connections, and the main tool in this search is not a computer, but the human hand that holds a pen or a brush. As long as it exists, the future exists too.

— Can tactile art be called ‘honest art’?

— For me, art is always a dialogue. A dialogue with the model, with the material, with the story behind the portrait. And the main task is to make this dialogue honest.

— “An honest dialogue” — that’s powerful. Does art exist that speaks so loudly it requires no words at all? Do you agree with the famous phrase: “Art doesn’t need to be explained. If it needs to be explained, then it isn’t art?”

— You can argue with that phrase. We live in a time when an artist is required to provide not just an image, but also a description, a concept, text. We explain everything. Of course, the highest piloting skill is when the work speaks for itself, and words become superfluous.

I was once at a group exhibition at the Union of Artists. I’m walking along, looking at works by different authors, and suddenly my attention is drawn to one small painting: it depicts a blue house with a glowing window, and this house itself seems to speak the title of the painting, you simply can’t call it anything else. I went closer to read the plaque, and it said exactly that: “Loneliness. Canvas, oil. 2023.” That is the very pinnacle of mastery.

But to achieve it, three things are needed: life experience, impeccable command of the craft, and, perhaps, that very sensual ecstasy. When you are at the peak of emotions, the work is born differently, because it acquires a voice. I experienced this myself when my song “Despair” was born. It was a difficult period related to a commission; I sat and wept from a sense of powerlessness. And out of that despair came a song — such a powerful, sincere hit that I’m still surprised by it.

And the most important thing: that painful experience ceased to be pain. It turned simply into experience, thanks to being transmuted into art. The song became my salvation. So yes, the best art truly doesn’t require explanations; it speaks to you directly because it is born from genuine feeling.

— If art were forbidden, would you continue to practice it?

— Yes. Especially since I do like to be a bit of a hooligan, but very much in secret.

— Since we’ve started talking about mischief: your exhibition titled “18+” removed all taboos around swear words. Do you think it’s possible for a person with a lot of life experience to go a whole day without swearing? And what is swearing – a bad habit or a conscious necessity?

— Is it possible to live a day without swearing? Of course, it’s possible. Why not? The question isn’t about the fact of using curse words, but about their overuse. And here, it seems to me, the habit of using filler words like “like” or “so” is much more harmful and irritating. And that image of a ‘boorish’ person who inserts a swear word every other word is probably already outdated.

Today, swearing is most often the language of expression: an outburst of emotions when you need to speak your mind, or a sharp joke in company. Chastushki at a birthday party, for example – why not? I’m not for eradicating it; I’m for dosage and even elegance. For instance, I really like how my in-laws sometimes toss around vulgarities – swearing in their mouths sounds special.

We are used to thinking of swearing solely as a destructive force, but we forget that in olden times it was a word of defense, and even a word of healing. Take even the scientific fact: when a person hurts themselves and immediately swears, they feel better. If a person holds back, it’s unclear where that unexpressed pain will go later. There are many subtle nuances here.

Personally, I don’t have a rule of “not swearing at all,” but I would reduce the amount of swearing in my life. Sometimes I can burst into the house and launch into a tirade; from the outside it looks ugly, but in the moment of breakdown it helps, as if you’re letting off steam.

After all, it’s not about the words, but the intonation and intention. You can be a model of an intelligent person and skillfully use swearing situationally. I know a lot of brilliant minds – doctors, cultural workers – for whom swearing is part of their working vocabulary. It’s a conversational language that allows you to convey a thought and an emotion briefly and succinctly. And if a person wants to destroy, they will do it with polite words too.

— Then what bad habit in your creative work would you most like to get rid of? Maybe laziness or procrastination?

— I’ve settled this question for myself once and for all: I have no bad habits in my creative work. I’ve accepted as an axiom: everything I did at any given moment was the best I was capable of at that time. I never return to finished works that are already in the studio archive to correct them. Recently, I was getting out some children’s portraits for an exhibition, unwrapped them, and thought: “Damn, Dasha, how did you even paint this? It’s so cool!”.

Yes, I’ve grown since then, my understanding of anatomy and materials has become incomparably higher. Of course, I could have done it differently, but I’ve made an agreement with myself: not to scold myself for the past, but to value it as a stepping stone. In my creative work, everything is good. I’m great.

— Such inner support probably defines the freedom in creativity. Does this freedom also remain in the relationship with the viewer? What is more important for you: to be unique or to be understood?

— That is a big and complex question. Being unique today is almost impossible. Being understood is more of an illusion: there are as many opinions as there are people, and I doubt that any artist has been fully understood by anyone. So, perhaps, the main task for an artist is to become understandable to oneself. I, for example, clearly see how all my seemingly different series and projects connect into one big story, but the viewer doesn’t read that yet.

From a commercial standpoint, uniqueness certainly provides an advantage. A developed style is a brand that sets you apart from others. But what counts as a criterion for uniqueness?

My own style is emerging; I experiment, try things, discard things. Someone once told me: “Your works are not an exhibition, but a phenomenon,” and I thought, why should I squeeze myself into the framework of a style if I can be a phenomenon myself?

I often hear feedback like: “I’ve never been to an exhibition like yours.” And I want to continue this trend—to create displays of paintings, turning them into unique events. I don’t yet know what I’ll be allowed to do in a museum… But I know for sure that I will go there in a tailcoat, because any phenomenon should be presented in a unique way.

— Do you ever expect a specific reaction from the viewer to your works?

— I do not expect any specific reaction. At all. For me, any reaction to my work is simply a fact, simply a person’s honest feeling. But, as it turns out, that is precisely the main sign of art. The very presence of a reaction of any kind already makes an object a work of art, regardless of whether the response is positive or negative.

Sometimes, sharp rejection or even anger speaks much more about the impact of a work than polite approval. If a piece has touched a nerve, provoked an internal response, debate, questions, it means it has succeeded. Silence and indifference, on the contrary, can become the opposite of art, but any emotion only confirms that a dialogue between the artist and the viewer has begun.

— So the very fact of a dialogue is already a value.

— Yes.

— What kind of compliment to an artist do you consider the most genuine, and which the most meaningless?

— I’ve come to a surprising conclusion: there are no meaningless compliments. Any praise is pleasant, but there is a difference in, let’s say, the ‘depth of field.’

The most valuable thing for me is when at an exhibition, every viewer finds ‘their’ painting. In each of my projects, there will be that one work that resonates with someone specific. One work will have 150 admirers, another will have just one, but a devoted one. That’s the magic: each painting gives something of its own.

— What personally touches you deeply?

— Expert recognition. If an average viewer says ‘beautiful,’ I will sincerely say ‘thank you.’ But if my teacher, a person with impeccable intuition, tosses out a brief ‘Dash, there’s something here…’—that is an event of a completely different order. Because they see right through it, they understand what it’s made of and why.

But, having been inside the professional community, I understood that any opinion, even that of a selection committee, is deeply subjective. Some artists look at the world as a phenomenon, others look through the prism of their own experience. And I’ve learned not to get upset by others’ opinions; they simply exist.

I don’t perceive criticism negatively either. If it’s constructive feedback on technique, for example, on anatomy where I might have made a mistake, I will only be grateful, because it gives me a reason to grow. And if it’s a matter of taste… I feel the material the way I feel it. It’s my choice. You need to remain honest with yourself, and the rest will follow.

— Where is that very foundation that allows you to remain yourself, despite the external noise and others’ assessments?

—In the end, everything depends on a person’s inner substance. Take, for example, the answer to the eternal question: what is good and what is evil—for me, it always lies in the context. Recently I read a wonderful thought: without light there is no shadow, and shadow is born only thanks to the light. It turns out that the light gives rise to the dark.

I often encounter this in my own experience. It seems like I’m just exhibiting projects, doing my thing, but there are always people who try to sow doubts in my confidence. But it’s just art! Just a way to show what’s inside. It’s just that I can allow myself to do it, that’s all.

I’m often asked: ‘Are you an artist (male form) or an artist (female form)?’ and I don’t care. I sign paintings as ‘Artist Darya Lyulyukova,’ but I don’t mind how people refer to me, because I like any derivative of my name. As a child, I didn’t like the name Darya, but now I adore it. I like it when people choose how to address me as they see fit: I can be Darya, Dasha, Dashka, Daryushka, Dashulya, Dashukha, it doesn’t matter. My dad calls me Donya, my mom calls me Dunyashka.

And in that, perhaps, lies that very light—the freedom to be different and to accept oneself under any name and in any manifestation. And the shadow simply confirms that the light exists.

— This freedom to be different… It must smell of some special kind of freedom. If your painting had to be described through a scent, what aroma would it be?

— It would probably be an aroma that reveals itself differently to everyone, the one you need at a given moment. If you felt like smelling an orange, there it is, fresh, unfolding before you.

If we consider the concept that an artist is merely a conductor of spiritual energy, then a painting, like a scent, gives each viewer their own particle of enjoyment. Maybe not immediately and not to everyone, but to those who need it, it will certainly convey something.

So, most likely, my painting is similar to a universal fragrance, capable of turning into vanilla, chocolate, or citrus freshness. It doesn’t impose a single sensation but softly opens up to those who need it here and now.

— Dasha, let’s talk about the future now. How will art change if its audience includes not only people but also algorithms and robots? Will we write and paint for them?

— No, we won’t. What would they need it for? An algorithm is a system that learns from existing data, combining ready-made elements; it doesn’t need something specially created for it. It will take information that already exists in the space.

And here we again come up against the main issue—the question of feelings. Paintings are created so that a person can feel something: drama, love, so that they find resonance and meaning. A creature devoid of emotions is incapable of this.

I rather imagine that robots will be led through galleries as if on tours. They will memorize data, analyze style, and this will be just another method of gathering information. And then you could ask an android to tell you about the technique and history of a painting.

But a robot could never say: “You know, the color palette of the painting ‘Sunflowers’ appeals to me less than the delicate blue of ‘Blossoming Almond Branches,’ because the latter evokes in me a feeling of fragile spring.” Such an assessment, which comes from the soul, can only be given by a person.

People should create art for people. Does anyone want to resemble an artificial intelligence? No. A person needs a human example, human emotions, human understanding. That is the essence of art.

— What will remain unique in art, something that algorithms cannot replicate?

— The answer seems obvious to me: an algorithm has no feelings. It hasn’t lived through the experience you put into your work; it cannot tell the story that burns inside.

I see how many artists use neural networks to “visualize” an idea from their head. But then, what are we to do with what’s inside if we delegate its expression to a machine? I don’t need suggestions; my task is to convey what I see and feel.

Fortunately, I’ve already developed a connection between my hand and my brain, and I can draw what I feel myself. I am interested in the process of pulling something out from within myself, not assembling it from ready-made puzzles.

Although I acknowledge that for speeding up work on sketches or for purely commercial tasks, neural networks are a powerful tool, I don’t use them. Simply because I find it more interesting to do things my own way.

— You speak about the process being more important than the result. But if only one painting remained from all your results, which one would you trust to speak for you?

— You know, I think that in the end, everything will disappear somewhere. Of course, one can achieve such fame that museums will store your paintings at a specific temperature and humidity, but everything physical will vanish, and only the digital will remain. That’s why I photograph all my works.

And if you dig deeper… I have an interesting theory that when a person dies, the internet page where their life was posted becomes a kind of monument. Perhaps in the distant future (if the internet still exists), among millions of such lost pages, my little monument will still remain.

— If creativity could be a bridge between the past and the future, what would you place in a time capsule? One of your works or something else?

— That’s a difficult question. So much bright and relevant work is being created now that choosing just one thing is almost impossible.

But if we’re talking not about a specific object, but about the main message I would like to pass on to my children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, it is the confidence that anything is possible.

I always follow a simple principle: if a goal arises for me, I check if at least one person in the world has achieved it. If they have, it means paths there have already been trodden; consequently, they can be found or one can blaze their own trail. I don’t know what my descendants will do, but I would like them to do it with love and reach precisely the heights they need, not what someone else needs. Now we finally understand that money isn’t everything: some want passion and ambition, others dream of a measured life, and that’s wonderful. The world has become wider.

So, into that capsule, I would put the faith that people can achieve anything they want.

As for material things… Perhaps I would leave them the silver Vietnamese bracelet I inherited from my grandmother. As for paintings… I’m a realist: for works to be preserved, we need museum workers, restorers, an entire system. So, leaving behind something physical that will last for centuries is an almost impossible task. I sometimes think seriously about this. But I come to the conclusion that ideas, the belief in possibilities, are far more durable than canvas and paints.

— What do you see as the most probable version of the future for humanity? And is there room for hope in it?

— Right now I’m writing a book in the post-apocalyptic genre, and in my world, civilization has rolled back to a slave-owning society. Such a scenario has only two paths: either humanity is smart enough to find a way out, or it isn’t.

History has shown us more than once that ideas can be good, but their implementation can turn into an outright failure. Take socialism, for example: to build a fair system, you need to try incredibly hard and, first and foremost, start treating people humanely, without intrusive propaganda.

When I hear that Elon Musk is sending people to Mars, I think: ‘Thank God! Let them fly away, I’ll stay here.’ I’m fine on this planet. I notice another trend: people are increasingly drawn to nature. Science is wonderful when it helps, not enslaves, but when you’re glued to your phone and life flies by in a few hours—that’s a move in the wrong direction. Whereas going on hikes, attending retreats, striving for simplicity—that seems good to me.

— Reflections on the future always come down to the question: what will we leave behind? This applies both to civilization and to the individual. If you knew you were the last representative of your profession, what would you do: create faster, more furiously, and in greater volume, or, on the contrary, would you bury all your brushes?

— A good question. At first, I’d probably be gripped by panic: they’re already at the door, and you’re shouting ‘go away, I want to be alone!’. But seriously, being the last of your kind on Earth is a colossal responsibility, yet the thought of burying the brushes and giving it all up isn’t even considered by me. Art is not an occupation; it’s the foundation of my life, and I would rather physically die than voluntarily stop drawing. But I also wouldn’t create in a state of hysteria, ‘faster and more furiously’.

Most likely, I would focus on passing on knowledge. I can’t say I’m drawn to teaching, but if you’re the last one on Earth, you have to try to leave a trace. My students and I would become researchers: we’d learn to create new paints, experiment with compositions. After all, the technology is mostly already known, so why not try? The world is full of colors that someone once discovered through trial and error.

Essentially, this is the foundation of foundations—to take one color and find a million of its shades: lighten it with white, darken it with black, mix it with other colors. It’s from such simple steps that all diversity is born. So, if I were the last artist on Earth, I would teach people to rediscover color, so that the world after me wouldn’t seem gray.

While living organisms undergo translocation, deletion, and duplication, we offer scientific knowledge without mutations – only useful discoveries and theories.

Thank you!