Category: Global minds

38 years of music: the band’s story in their own words

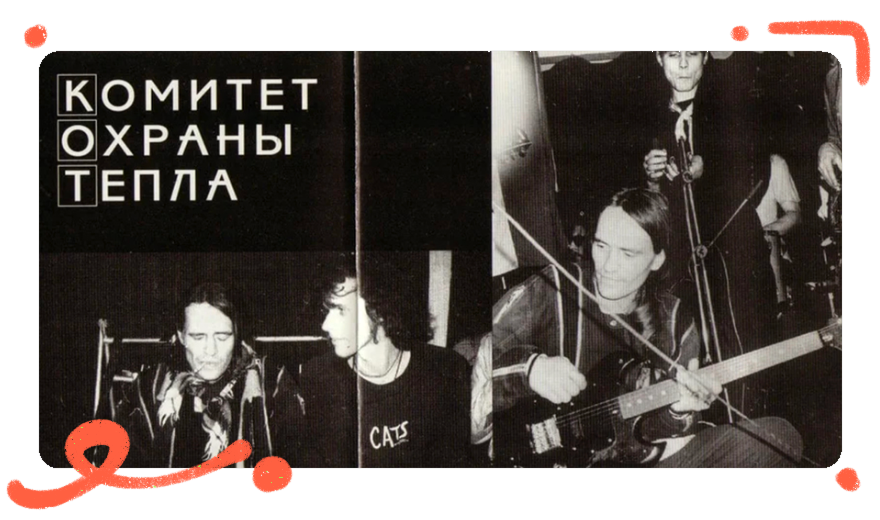

This interview is dedicated to the creators of the cult underground band “Komitet Okhrany Tepla” (The Committee for the Protection of Warmth):

its founders — Sergey Yuryevich Belousov (Oldi),

Valery Semchenko (Sten);

its ideological inspirers — Andrey Brytkov, Andrey Kolomyitsev, and Ira Metelskaya;

to all listeners and admirers,

as well as to the past, present,

and future fans of the band.

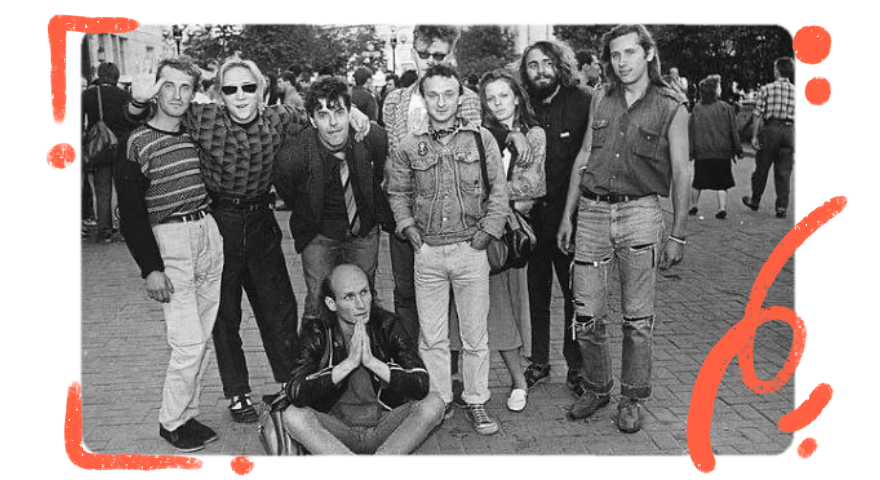

The harsh pre-perestroika years. The Soviet Union. The gray face of communism and slogans about how great life is, long stripped of any relevance. And suddenly, in the midst of this frozen space, a band emerges that voices things it was dangerous even to think about — and does so to the rhythm of reggae.

“Who needs reggae in this country? No FM station will ever play a single track of theirs during prime time,” producers asserted confidently. “Who are they? We’ve never heard of them!” declared, one after another, the record shop and kiosk owners who had made their fortunes selling Metallica albums. “No one will buy this.” But the creators of this raw, truth-revealing art didn’t care. What mattered to them was making real music — and that’s exactly what they did.

At the band’s concerts, the musicians gave it their all. The performance troupe might fry eggs right on stage, while makeshift tanks rolled through the crowd. Komitet’s music spread underground, within its savvy, all-knowing circle of insiders. The frontman’s voice — warm and rough, like ancient wood that’s lived through centuries — echoed with hints of Vysotsky, the wise simplicity of old bluesmen, and something entirely its own, something elusive. It needed no explanation — it simply sounded like the truth. Komitet’s songs dwell in a unique world — at the intersection of imagination, memory, and longing. A space built from sand, ash, and snow, where the heat of Jamaica and the winds of the North coexist. It can be harsh, kind, uncomfortable, and utterly real. And in their songs, there’s also a certain kind of sky — vast, high, and clear — the kind you only find in Africa, and only for good people.

The editorial team at The Global Technology magazine, paying tribute to the work of this legendary band, decided to explore how the music was born, what secret warmth it holds, and why it strikes a chord even in the most indifferent hearts; to talk about insane acts in the name of art, about meaning, sound, and the silence between the lines.

The band’s permanent drummer Alexander Vereshko was the one who answered our questions.

— Alexander, all of us are big fans of Komitet Okhrany Tepla, so this interview is especially meaningful to us.

— Gerda, thank you.

— When you listen to Komitet’s music, you get the feeling that these songs weren’t written to be played endlessly on the radio, but rather so that one single person might smile to them. When you created Komitet, surely none of you were thinking that your songs would become “folk songs” — and that every new generation would find something of their own in them. Maybe now, 38 years after your first concert, you can answer the question: why do we love listening to your music so much?

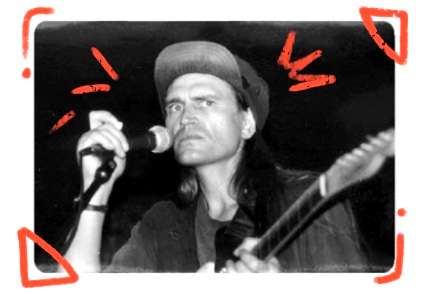

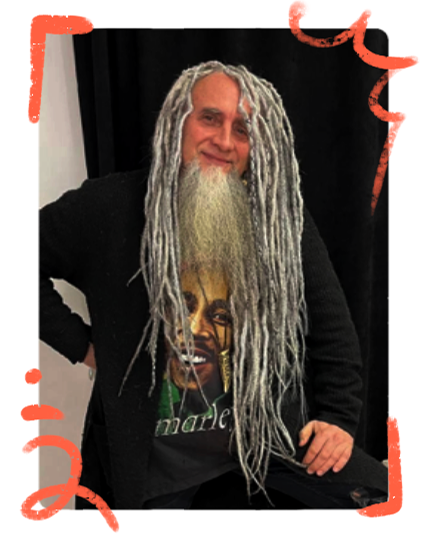

— The answer is very simple: because we are all Komitet. That phrase belongs to the group’s founder, Oldi — Sergey Yuryevich Belousov. We didn’t know who we were. We weren’t thinking about fame. We were just high on each other — and that high had Oldi at its core. Without him, none of this would have taken off. He was the authority. He was the nerve.

— Thank you for your answer, Alexander. Let’s then talk about the band’s founder. These days, many frontmen of rock bands lament that Oldi was an unfairly overlooked figure. What was Oldi like, personally, for you?

— What was Oldi like for me personally? That’s a tough question. Because, to be honest, the first ten years of Komitet — those were the truest years. Everything that came later was important, of course. But those ten years — up until the mid-’90s — that was pure nerve, pure joy, pure freedom. And all of it revolved around Oldi.

He was very tough. I even used to call him Stalin — he could hit you with a word, cut you deep in a second. And I was soft. For years, people came to me to complain, to cry — I was the one with the shoulder to lean on. I used to joke and call myself “Oldi’s mom.” We were like two forces — he broke things, I glued them back together. And still, we were together.

Toward the end, I told him, “Seryozha, I can only love you from a distance.” Because being near him meant forgetting yourself, erasing your own space. Like all geniuses, he lived through others. He needed someone close — only then was he at his strongest, the true leader. Alone, he would lose himself, deflate.

But it wasn’t some kind of performance. He was real. I gave him my soul — truly, honestly.

He was incredibly charismatic. He was the kind of person who could change the atmosphere just by being there, restore discipline in the band — even if, let’s say, he didn’t always fit the mold. I don’t even know how to explain it, but his way of seeing life and music was so unique that everyone around him just knew: this wasn’t just a frontman. This was someone who saw the world differently.

— What part of Oldi’s worldview was especially close to you?

— Oldi was a true philosopher. He could speak so deeply, in such a multi-layered way, that sometimes it felt like his words weren’t just phrases — they were entire worlds you had to decipher. He always used to say: “Never ask for anything! They’ll offer it themselves, and they’ll give it themselves!” It sounded like a joke, but it always turned out to be true. He lived without fear, confidently, and could get anything he wanted with ease — but he never asked. Things just came to him.

He could give you some expensive gift and then say, “Here, take it — but I’ll take it back later.” And somehow it felt completely normal. Not that he did it with bad intent — it’s just that things flowed to him and from him effortlessly. That was part of his magic.

Oldi knew how to tell a story simply, clearly — brilliantly. He could charge you up, flip a switch in you. And the main thing is — that didn’t only happen in rehearsals. We hung out outside the studio too, like friends. And that was even more intense. The stage — that was just a small part. Life with him — now that was magic. Yes, strange. Yes, sometimes heavy. But magic.

And we all had to pass through this kind of sieve: some accepted it, some didn’t; some stayed, some said, “Not for me.” And the ones who stayed — that’s Komitet.

— Alexander, tell us how you joined Komitet Okhrany Tepla.

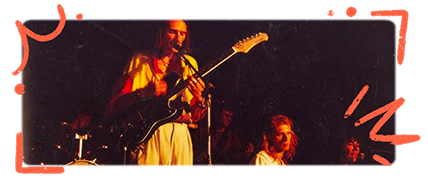

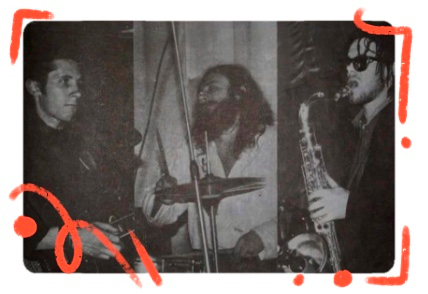

— That’s a story of its own, really. I was brought into Komitet by my friend Andrey Brytkov. He was playing sax in the band at the time and just said to me, “Come on, we need a drummer.” By that point, something like fifteen people had already played drums in the band before me. In the summer of 1987, I came to a Komitet concert at the Sailors’ House of Culture — just to check out their music — and I was blown away.

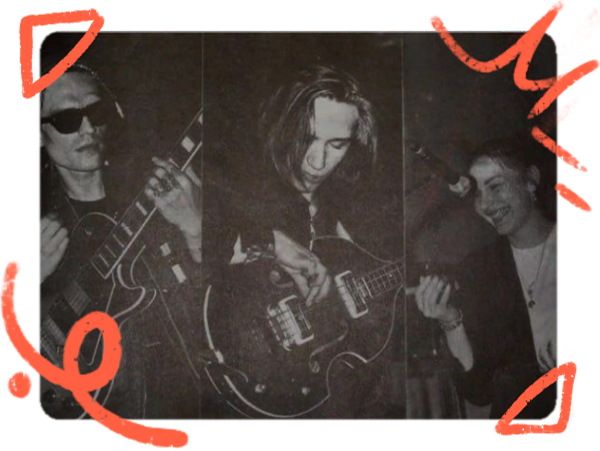

Imagine: Soviet times, it’s 1987, and on stage there’s absolute madness — two bass players, four guitarists, a violin, a flute — and all of it wrapped in wild theatrical performances that turned into real shows. I was stunned. It was something totally new. I was raised differently — strict, disciplined — and it was a different era, too. And suddenly I saw this… hypnosis happening on stage. It was a completely different environment. A whole atmosphere. I’d stepped into a world I’d never known before.

— And did you fit in with the band right away?

— I didn’t understand anything when I joined Komitet. Seriously. Funny enough, the same thing’s happening to me now — when young guys join the band, they say: “Our life split into before and after.” And I get it — because I had the exact same experience. It really was like reincarnation. Before and after.

I grew up with a strict upbringing — and suddenly I found myself in a completely different world. It’s not like I just walked in and everything clicked — no. It took time to absorb that new world.

And besides, this wasn’t just a band. It was a universe. And the people in it — they weren’t ordinary. It was real underground. I was just a regular guy who could bang on the drums, but around me were real characters. Like Yan, nicknamed “Codex” — he used to perform on stage with binoculars and an inflatable mattress. Or Ira Vagapova — a master of rhythmic gymnastics, performing in a ballet tutu. There were shows, music, freedom. I just stood there with my jaw on the floor. Honestly — it changed my psyche.

Oldi — now he was a polarizing figure. Seriously larger than life. He charged people up. He set directionPeople who came in contact with him started moving in his orbit — not because he made them, but because he was magnetic. And when I joined Komitet, I didn’t understand it all right away. I’d already been in the band a year, two, three — and I still hadn’t fully grasped what kind of space this was. It took time, as they say. Playing reggae isn’t easy — you have to feel it, accept it. Some get it fast, some need more time — everyone’s different.

— Alexander, thank you for being so open. Tell us — how did the name Komitet Okhrany Tepla (Committee for the Protection of Warmth) come about?

— Oh, you might be surprised — at first, the band was called Free Member.

— Really?

— Yep. It started as a kind of joke band. But Komitet — that’s not just a name. That’s an idea. Remember that old cartoon about Captain Vrungel? “What you name the boat, that’s how it’ll sail.” Same thing here.

Komitet Okhrany Tepla — it’s a warm, Russian name. Familiar. Oldi always said: This isn’t a band. It’s a movement. With its own philosophy, its own perspective. He was a born leader. And he had a vision. It’s like Lenin with the revolution — no matter what you think of him, there was an idea and there was a leader.

— You said that so beautifully, it makes me want to go back and listen to your songs all over again — with new ears.

— Thank you.

— Alexander, would you say that Komitet’s songs are about pretty much every human emotion and experience? How was the music born in Komitet?

— Everything was actually really simple. Oldi was never without his guitar. Just like Stan — our bassist — he literally slept with his instrument. They were constantly playing something. They lived with their guitars. Oldi would come to a rehearsal, bring a new set of lyrics, strum a bit, sing the way he imagined it — and we’d start building our own parts around it. And right away it would begin: “That’s not it!” “That’s wrong!” Sometimes it would even escalate into insults, people getting kicked out of rehearsals. That’s how Andrei Kolomyitsev left, for example. He was a great musician, but Oldi could say to anyone, straight to their face: “You’re playing shit.” Musicians often took offense — some would storm out, some never came back. But Oldi knew each person’s worth.

Sometimes, a few days later, he’d find a way to talk to you.He wouldn’t exactly apologize — but he’d say something in a way that made you realize: yeah, he regrets having gone too far. And you’d come back. Happened to me too. I remember before our final concert in Kaliningrad — five minutes before going on stage — I snapped at him: “What’s this? What’s this computer thing Zhenya Milovanov just brought in?” And Oldi just said: “Don’t like it? Then get out.” Just like that. But I knew — that’s Oldi. That’s how the process worked.

We fought, we fumed — but the work mattered more than the ego. Because there was an idea. And personal drama… well, to hell with it, as they say. Some could handle it, some couldn’t. Some thought they were too cool to put up with yelling and insults — even from Oldi. But the ones who stayed knew — this wasn’t about ego. It was about giving birth to a song.

— And since we’re talking about what went on behind the scenes, what was the rehearsal atmosphere like in Komitet?

— It was something completely new. In Kaliningrad — especially back then — there was nothing like it. Nothing was like in other bands. We had rehearsals at the Seafarers’ Palace of Culture — Monday, Wednesday, Friday. We’d gather on the steps outside and wait until all the musicians had arrived — only then would we go inside. Of course, there were no cell phones at the time. A lot of people thought Oldi was just a scatterbrain, a slacker — but in reality, it was totally different. We had strict discipline. He knew how to organize, and he was tough. But that discipline — it worked.

I remember my first rehearsal — the drums were set up right in the middle of the room, and the musicians formed a circle around me. Oldi said: “Okay, everyone play to the drummer.” And I was terrified, honestly. I was a hard rocker. I didn’t even listen to reggae. I was into totally different styles back then.

Actually, I started out with music at age ten — my folks put me in music school. First I played the balalaika. Then I switched to a seven-string guitar, and eventually a six-string. And the first time I ever saw a real drum kit was when I lived with my aunt. She had a tenant — a surgeon at the regional hospital — and he was a drummer. He took me to a rehearsal, and that’s when I saw it: A full drum kit. Shiny. With a kick, a bass drum, real cymbals. I’d only had a round toy drum before — the kind they used in Soviet pioneer parades, for flag ceremonies and school marches. And suddenly — this! It was 1980, I was 14 years old — and from that moment, I became a drummer.

— Do you remember the moment when music stopped being just a hobby — and became a challenge, something you were ready to go all in for?

— That’s a great question. Yeah, I did have that turning point. At first, I played like a regular drummer. But one day at university, this guy says to me: “You play like John Bonham.” And I go: “Who’s that?” — that’s how I discovered Led Zeppelin. They’ve been my favorites ever since.

We also had our own band back then — it was called The Ninth Circle. We were a tight crew. But then one day, this Kaliningrad drummer, Vova Peshkalo, said: “That Vereshko guy — he’s talentless.” And someone made sure I heard about it.

You know, that really got to me. The word “talentless” just drilled itself into my brain — I couldn’t shake it. I’ve always had a strong sense of pride, I’m a total perfectionist by nature. Back in school, I was top in sports, top in the orchestra, top on the balalaika. Things usually came easy for me. But this? Talentless? No way. I wasn’t going to accept that. I decided I had to prove the opposite. Back then I lived in a Khrushchyovka. I built myself a homemade drum set — out of wood, with rubber stretched over the top. Bought a metronome, started training. I even got proper drum notation from this top-tier drummer — Igor Tokmyanin. And I did all this not because someone made me, but because something inside me was on fire. I needed to prove myself. I wanted to be the best. Really, I did everything I could to dive headfirst into rock’n’roll.

— So being part of Komitet changed you — both as a musician and as a person?

— No doubt about it. As a kid, I was incredibly self-conscious. Like, really bad. But somehow Komitet burned that out of me. I went from being someone buried in insecurities — to someone with almost none at all. Not just toward the center, not to some healthy middle ground — but straight into the opposite extreme. And honestly? I’m glad it happened that way.

I know what it’s like to be full of self-doubt. I’ve been there. Some people haven’t. Some people just sink into it, shut down, bury themselves alive. But really — it’s easier than it seems. There’s this cliché, sure, but it’s true: Once you turn your flaws into strengths — there’s nothing left to fear. Even if something embarrassing happens — that’s no reason to be ashamed.

There’s a thought I always come back to:“Never look at yourself through someone else’s eyes.” Don’t live your life through someone else’s lens — someone else’s torn tights. Because for one person, that might be a disaster. For another — it’s nothing. Someone might even see something beautiful or unique in it. And someone else might be horrified. So what — you gonna twist yourself to please everyone? No. That’s not what life is about.

So walk forward with your head held high — flaws and all. If someone points one out, just say: “Yep. Thanks. I’m aware.” And keep moving. With dignity. You’ve got to own your hang-ups, your mistakes — and say them out loud. That’s so important. Because as long as you keep it all inside, it eats at you. But once you speak it — it lets go. And it gets lighter.

— Alexander, then let me ask this: what’s the craziest thing you’ve ever done for music?

— Happy to answer that. So, picture this: I was just your average guy with a drum set. Sometimes people would say, “Oh, Sanya, that’s awesome, you play so well,” and honestly, I was proud of that. I’ll admit it — I like showing off. That’s just me.

Anyway, after school I finished ten grades and tried to get into a military academy. My dad was in the military, but I wasn’t thinking of continuing the family line or anything. Just thought, “Military? Alright, let’s go.” During the entrance trials, I ranked first everywhere — I had athletic credentials in five different sports back then. Physically, I was in top shape. But on the physics exam? I only scored two points. That was it — game over.

I still remember — one of the warrant officers told me, “Come back, I’ll sort things out.” So I came back, but another officer looked at my scores and said, “Why are you even here? You got a two. Get lost.” Yeah… that stung. I rode home from the Borisov Academy (it still had Zhdanov’s name back then) thinking, “You know what — fine.”

After that, I enrolled in KTI — our tech university. I was going to be a food engineer, working with fish products. I flunked the math entrance exam right away, but somehow managed to pass chemistry. I remember during the oral, someone asked me, “You remember the formula for methane?” I mumbled shyly, “CH₄…” And boom — I got in.

For my parents — simple rural folks — this was a miracle: their son was going to university. But me? I had no idea what “higher education” even meant. I was way more into music and sports. I always weighed around 60 kilos, ran like a madman — track and field was my thing.

I graduated in 1987. Right around then, Komitet started playing gigs, going on little tours. Then came the state job assignment — they sent me to the Trawler Fleet base, out at sea, for six months. It was a ticket to a stable life. All sorted.

But the only thought spinning in my head was: “How are they gonna play without me?” So I put my diploma on the table and didn’t go to sea. I chose rock’n’roll instead. It wasn’t about money. It wasn’t about anything, really. It was just — pure joy. Freedom. I didn’t even realize back then that this was real freedom.

That was the fork in the road. I took it — and I don’t regret a single second. I have no clue who I’d be today if I’d gone with the fleet. But I chose the drums.

— Alexander, thank you for such a touching memory! Let’s recall the moment of recording the CD. It’s hard to believe now, but in the early days of the Committee, fans mostly got by with homemade tape recordings — not the best quality. After so many years of this “home sound,” how did it feel to finally get into the legendary Ostankino TV center? What did you feel then?

— Oh, the recording was a lot of fun — so much fun that I barely remember some parts. You know how it goes.

If I recall correctly, Oldi was living in Kaliningrad at the time, and he had a landline phone — I think the number was something like 4-44-15. Mobile phones didn’t exist yet, and the city’s phone network was spotty at best. Then we got a call from Moscow. It was from the show “The Ferris Wheel.” They said, “We want to invite you to record a vinyl record right at Ostankino.”

Of course, we agreed, even though we had to cover our own travel and accommodation costs. We packed up and went. We stayed at Gera Morales’s place and went together to the TV center. While we were getting our passes and all that, it turned out: the recording equipment was there — but no drums. Gera called some friends, and they brought us drums. The first day was spent setting up and meeting our sound engineer, Olga Klimova — a very beautiful woman. Before that, she mostly recorded symphony orchestras and had never heard reggae. Our producer was Natalia Grechishcheva.

We recorded in a room that looked more like a school gym. Then the recording began: they put a metronome in my ear — and… nothing worked. They took it out — and suddenly everything flowed smoothly. We recorded the whole rhythm section live: guitar, bass, drums — all together, not in separate layers like usual. Because we were a live band, and it was important to capture the spirit of a live performance.

By the way, nearby they were filming the comedy show “Kabachok 13 Chairs,” and we were running around the buffets and corridors of the TV center — quite a sight. I quickly bonded with Olga, our sound engineer; she literally discovered reggae and Bob Marley through us. Funny thing — at the start of the track “So Tell Us, Jah!” you can hear my laughter — they left it in the track. While recording that song, I looked at Andrey Brytkov, and his expression was so funny that I couldn’t hold back.

When we finished all the planned tracks, there was space left for one more song. So, without ever playing it before, we recorded “Marivanna.” Let’s just say it was a stoned improvisation. Gera and Alexey Ramensky (Ales) joined in on backing vocals and percussion. If I remember right, one of the mixes was lost and had to be redone.

A month later, we returned for mixing, then waited for the album’s release. Then we got a letter: “Due to the presence of invective language, release is impossible.” But later, our recording was sent to Austria and released there as a CD. That was pretty cool for the time. This recording is considered the only professional recording of Komitet. The song “Prison Rock” was already playing on the air during Roma Nikitin’s show “Quiet Parade” alongside tracks by Kalinov Most, Survival Guide, Rabota Ho, and others. We stayed in first place for several weeks. When the boxes of CDs arrived — that was a real event for us. Each musician got a stack. I got 20 copies and gave them to “Taxist” — my exact namesake, Alexander Vasilievich Smirnov, who owned a legendary kiosk at the Northern Station. Oldi was supposed to bring me 10 more, but something went wrong and he never delivered them. And so our album “Wounds of Warmth” came out. All of this was like one big breath, one crazy story you never forget.

— Apparently, a recording from that CD somehow made its way to me. So I’d like to ask about the song “Africa.” Even though it has a Jamaican and even African vibe, it’s infused with a native DNA; that’s why now it’s become a folk tune — people hum it, whistle it, tap it out without even realizing it has an author. And what’s most surprising is that sometimes the song “Africa” is associated with the band “Lyapis Trubetskoy.” How did that happen?

— Gerda, do you want me to tell you something about the song “Africa” that almost nobody knows?

— Absolutely!

— Remember, in the song “Africa” there’s a female vocal part that sings this curious phrase: “Diva fura Djambana?”

— Of course.

— It all started as a joke: Brazilian soap operas were all the rage back then, and we laughed till we cried. Ira Metelskaya and Alexey Ramensky — Ales, whose eyes were shining like a schoolboy’s — they came up with that very phrase. It fit so organically into the song, just perfectly. To be honest, when we sang it, we couldn’t imagine “Africa” would become so famous. But we nailed it — good job.

There’s another little-known fact about this track. Throughout the song, you can hear real African drums. Well — yes, the drum sounds are real, but they weren’t played live. This is thanks to our sound engineer — Olga Klimova, a girl from Ostankino. When we came to record — in the assembly hall — there was no orchestra, but there was Olga. Olga, a very bright, talented, and pretty girl, had never heard reggae before, but after talking with Oldi, she caught the idea. She understood it, felt it, and was so inspired that she found those African samples herself and inserted them at the beginning and end of the song. It turned out just great.

Now, of course, it’s easier: guitar, buttons — and it’s like you’re already in a studio. But back then, it was all real. “I dance reggae on dirty snow, my shadow on your shore… Africa!”

— Thank you, you described it so vividly — I could immediately picture everything in my mind. Still, why is this song associated with the band “Lyapis Trubetskoy”?

— Here’s the story: we often played in Minsk and frequently visited the rehearsal base of Sergey Mikhalok — the lead singer of “Lyapis Trubetskoy.” He also has an interview where he recalls this. Sergey shared that he’d long wanted to sing the song “Africa” but didn’t know how to get official permission in a proper way.

And then one day, almost right before his death, Oldi was in Moscow, in a very bad state. He needed to fly — I think to Crimea — but wasn’t allowed on the plane. Imagine: an electronic ticket, no money, and they just wouldn’t let him board. The airport. Alone. No one around. Oldi called Katya, his wife. Then he started calling everyone in Moscow. No one answered, no one came, everyone bailed. The only person who came to help was the director of “Lyapis Trubetskoy.” He arrived, took Oldi with him, and they spent three days together. And as a sign of gratitude, Oldi gave the band permission to perform “Africa” completely free, no formalities.

And then a real mystery happened: on November 4th, the guys released a music video for this song — and on the very same day Oldi passed away. Can you imagine?

After his death, we still performed at the “Okna Otkroy” festival in St. Petersburg. The “Lyapis Trubetskoy” guys were there too. I went to their tent; they had to go on stage in five minutes, but we managed to have a quick drink of cognac. And you know, in St. Petersburg, people even asked: “Is ‘Africa’ really your song?” because many had come to know it through those guys. That’s normal. Although at our concerts, people often say our original version is still closer, more authentic, and more heartfelt.

— Alexander, if you were asked to write a soundtrack for a movie about your life, which three songs would absolutely have to be included?

— That’s a tough question. Probably because it’s a good and provocative one at the same time. It doesn’t seem scary, but no one has ever asked me that in my whole life. And to be honest, I never asked myself that either, though it seems like such an obvious question. But as soon as you start thinking about your whole life, you catch yourself almost saying “they” instead of “I,” because everything is so intertwined for us.

If I talk about songs, the one closest to me in meaning is “Ne very mne” (“Don’t Believe Me”). There’s something in it I understand on a feeling level: “They tell you: ‘You’re born to crawl’ — don’t believe it! They tell you, but don’t believe it. Here’s only my enemy, here’s my trouble. Fire sirens keep me awake, but I’m not alone — I haven’t cared for a long time.”

I’d take “Gematogen” as a soundtrack for my life too:“Hoffman told me: ‘To live, you have to lie.’ It’s a vicious circle: easier to sit than stand. But it’s better to stand honestly than to sit like a prostitute. I avoid traps, I gnaw through the net!”

And also the song “Confrontation”. It has lines like: “I won’t give metal our warmth.” Back then, that was important. Between Oldi, as a representative of reggae (I won’t say “rastaman,” but still), and metalheads there was a kind of healthy competition. Some laughed at metalheads, some laughed at us. That was the spirit of the time. And the song said: “I won’t give metal our warmth” — because it was ours, alive.

— If you could perform a concert anywhere on Earth — in a swamp, in Jamaica, on a rooftop overlooking a sleeping city — where would it be?

— You just asked the question, and already images are forming in my mind: one, two, three. I imagine the moon shining, the river quietly splashing, and the Cathedral standing majestically — one of Kaliningrad’s main landmarks. Silence, no cars. And we’re playing on the Estakadny Bridge.

I really love Königsberg — Kaliningrad. For me, Jamaica is more of a dream. Our small town is like a little Jamaica, at least to me. And even if we were in Jamaica, the native people of that island, unfortunately, wouldn’t understand us. Yes, we play reggae, but our music is local, northern — that’s why we cherish warmth so much. Reggae in Jamaica is different — it’s rooted deeply, and it would be hard for us to understand it.

— Alexander, the next question might seem heavy, but I can’t help but ask: does music destroy or heal?

— You see, you said the question might be heavy — and it really isn’t easy. Because yes — music can heal, but it can also destroy. I’ve asked myself that question before, and I have an answer.

For me, music is grief. Can you imagine? Not inspiration. Not joy. Grief. Because my friends — the ones I played with, who lived through this music with me — now lie in cemeteries. They, like me, gave up everything for the stage, for rehearsals, for that fire. It wasn’t just music — it was a way of life. It was everything. We chose this path, and the price was life — their lives. And I stayed. At the last concert, I wanted to dedicate everything to them, and wanted to say it into the microphone. But I forgot. I forgot, and I still can’t forgive myself for that.

So when someone starts getting philosophical and says things like “music is emotions,” “music is pleasure”… For me, music is grief. That’s my answer.

— In your answer, there’s a strong attachment to that time and to the music. At what point did you realize you needed to continue the musical path of “Komitet”?

— I took it on because I feel that everything connected with “Komitet” was and still is my story. I’ve always been very protective of Komitet’s music, because Oldi was the undisputed leader — his ideas, his words were what drove the whole team. I always said that without him, there wouldn’t be us, or all of this. Oldi would come on stage and hypnotize everyone. That’s charisma, you know? You can’t learn it, he was special.

But if we talk about Komitet, I’d give 70% of the credit to Oldi, and 30% to the guys, the musicians. Until the mid-90s, when the original team was still there, that was the real Komitet. But then Oldi started traveling all over the country, hiring new musicians, and for the audience everything changed. When he started playing with other musicians, even famous ones, we lost what we had, because nobody really knew how to play reggae properly: musicians played without rehearsals, and of course it wasn’t the same Komitet anymore. The musical core was gone.

After the mid-90s, I saw a lot of material, but very little was truly performed. There were a few video recordings, but we never really managed to preserve that golden lineup we had. Oldi had different musicians, different ideas, but the atmosphere was gone. And when he left, there was no soul in what happened. There was no soul in the music. And now I’m trying to bring that music back. I’m not a singer, never was, but I know how it should sound. What we’re doing now is real work — music.

Now, when I see how the audience responds, I realize we’re on the right path. The guys with me are a mix of experience and youth, and you can really feel that in the music. I’m not trying to reincarnate Komitet, but I want to continue the story, to extend the path. I always said my youth passed in Komitet. At some point, Oldi took the flag and carried it, and now I carry it further. And even if others don’t understand — it doesn’t matter. I know what I’m doing, and for me it’s absolutely important to preserve the name and bring the soul back to the music. Some say that after the mid-90s the music disappeared, and I agree. But we haven’t lost everything — we’re still playing, and I do it for myself, for those who understand what happened back then, and to bring the music back to Komitet.

— And one last question: if one of your lines could become a motto or a talisman for everyone who hears you on the street, what would that line be?

— That’s a very serious question. I have favorite books, favorite movies, and favorite fiery phrases — many of them. They help me in any situation. Right now, the line that comes to mind is from a Komitet Okhrany Tepla song — “Not the time to love“: “Those ahead, and seemingly behind you, but things got twisted so much that you fucked yourselves.”

It’s about situations, about friends, about those who seem to be for you, and about how it’s always important to stay honest with yourself — because sometimes you can’t take things back. And maybe it’s about those moments when you realize that all the sincerity you have and ever had isn’t really needed by anyone.

“And now for the soul, blow a hurricane,

Take me with you, take all the guys.

Lift us to the sky and let us fly in all four directions:

Who goes where, who’s with you.

And those who didn’t understand, send them home.

No matter how much you sing here, shout, drink, or get high —

Two times two is two, three times three is three.

Simple arithmetic, don’t try to fool me.

This is not the time to love. Not the time to love.”

Not the time to love, but we still love anyway: some love music, some love freedom, some love different little pleasures, some love themselves. And you, no matter what, keep love inside you. Keep love and protect the warmth.

According to the Big Bang Theory, the Great Explosion of discoveries starts right now.

Thank you!