Criminal forensics: From ancient rituals to modern science

“You can put everything back in its place, except for dust. Dust is eloquent.”

Sherlock Holmes

A dim light filled the detective’s dusty office. Stacks of unresolved cases, an old computer, and an ashtray with a still-smoldering cigarette set the scene. The detective paced back and forth, measuring the room with his steps, deep in thought.

A valuable painting had disappeared from the city gallery. All signs pointed to a professional thief: no evidence, no witnesses. The city police commissioner, unwilling to dwell on the case for too long, accused the first person he saw that fateful morning — the gallery’s night watchman, old Mr. Dean. A simple man with no appreciation for art, he had no grasp of the gravity of the charges against him.

As is often the case, it was obvious to everyone that Mr. Dean was innocent. Everyone except the commissioner. This was precisely why the detective took on the seemingly hopeless case — he could not stand idly by while justice, long corrupted in this town, crushed yet another innocent person. But no matter how hard he tried to crack the case, he kept hitting dead ends.

For as long as humankind has existed, it has sought effective methods of solving crimes. But how would our detective fare if he found himself in the Middle Ages, armed with all the technological advancements of the modern era?

Dark times dictate dark decisions

To find a solution to our problem, let’s look back to ancient times. People lived in tribes then and had no concept of a judicial system. Things were simple: crimes were often committed out of revenge, and the victim usually knew who was responsible. Moreover, the only law recognized back then was the law of blood vengeance.

So, in such a case, the culprit of the theft would almost certainly be the cousin uncle — the gallery director. Never mind that there’s no evidence! He’s guilty, if only because, since childhood, he never liked his nephew and always made things difficult for him.

A little later, when the world transitioned from personal revenge to recognizing legal norms, the situation began to change.

For example, while in an African tribe, the detective would have to perform a special ritual dance, moving around the suspects and carefully sniffing them. By the intensity of the smell of sweat, he would be able to tell who was truly guilty. The commissioner would likely be the first to come under suspicion, as the constant coffee consumption at work often left him with visible sweat stains on his shirt. Or perhaps the gallery’s movers, who also tended to sweat frequently.

In another ancient Indian tribe, everything was decided by strength and coordination. The suspect in a crime had to quietly and steadily strike a gong while the investigation was underway. And if, at the sudden mention of objects related to the crime, the strikes became harder and louder, it was considered proof of guilt.

By the way, detectives and investigators didn’t exist in those dark times, and the victim had to bring the suspect before the court themselves. Therefore, we don’t recommend that the detective in this scenario linger here for too long, as his services are not yet needed.

Oh, Holy Inquisition

Let’s try to find answers to our problem in the Middle Ages. By then, judicial practices were actively developing in Europe. Even before the Inquisition, there were equally terrifying “God’s judgments” — ordeals. This method helped determine a person’s guilt or innocence through special trials: by fire and water.

The water ordeal was particularly popular: the suspect would be bound and thrown into a body of water. If they managed to swim out and survive, they were considered guilty because even the water could not accept such a sinful person. However, those who drowned were acquitted. So what if they were dead — they were innocent.

There were also less brutal trials, such as the bread and cheese trial. We think this one would suit our detective better, especially since there’s no body of water nearby, and poor Mr. Dean deserves some sympathy.

To determine guilt, the suspect was given a piece of church-blessed bread — a prosphora — and a hard old cheese. While the priest recited a prayer, the suspect had to swallow the food. If it got stuck in their throat and they choked, they were immediately declared guilty.

Today, we could say that psychosomatics played a big role in this trial, as many criminals choked on the bread due to the immense pressure they felt.

We won’t apply such pressure to Mr. Dean in this case, so let’s assume he easily swallowed the church bread, which once again proved his innocence.

But we can’t leave out another, rather comical, method for identifying criminals in the Middle Ages: the donkey tail trial. The animal’s tail would be painted and tied up in a dimly lit room. The suspect had to approach and touch the donkey’s tail. If the donkey screamed, it meant the person was guilty. The logic was that the guilty person would avoid touching the donkey’s tail to prevent it from crying out, thus keeping their hands clean.

It’s hard to say who invented such twisted trials to prove someone’s guilt, and even harder to understand why medieval people trusted them. But we move on, toward more humane and joyful times.

Long Live Deduction!

We’re sure that by the 19th century, more suitable methods had already existed for solving our tangled case. This century was renowned for scientific and technological progress and rapid industrial growth. People began to leave villages in droves and move to cities, which, as a consequence, led to an increase in crime.

The old methods of tracking down wrongdoers were no longer enough, so the field of criminalistics began to develop rapidly. The police started keeping records and identifying criminals based on physical characteristics, compiling these data into a catalog that helped expose those who repeatedly strayed onto the wrong path.

At the same time, forensic medicine and fingerprinting emerged: the analysis of fingerprints became a true breakthrough of the time! The police and courts began to pay closer attention to the crime scene and the evidence found there, of course, with the help of technological progress. It became clear that any small stain found at the crime scene could be used in the investigation’s favor.

19th-century doctors learned to distinguish animal blood from human blood, and even female blood from male blood using reagents, microscopes, and sometimes even by smell.

It looks like the detective will have to return to the gallery for a thorough inspection; maybe he missed something important. Indeed, the police and the detective carefully examined the main gallery hall but didn’t give attention to the other rooms: they were simply not allowed in, which raised suspicions.

The gallery was empty, the director had left for an important event, and the new watchman, who had replaced Mr. Dean, was peacefully snoring at his post. The detective walked through the exhibition hall and made his way to the central rotunda, from which narrow corridors branched out like a labyrinth, leading to technical rooms and offices.

Since the painting was stolen, the gallery had been closed and was not accepting visitors, so everything remained the same as it was at the moment of the crime. In the corridor leading directly to the director’s office, the detective noticed something he hadn’t seen before — the dust on the windowsill behind the heavy curtains had been partially wiped away, and on the brown parquet floor, there was a barely noticeable reddish stain. Was it blood or tomato juice? The expert examination would decide! These clues gave the case a new direction.

But how could there be blood here? According to Mr. Dean’s testimony, he had been the only one on duty the night of the theft, and everything in the gallery had been calm.

The detective pushed aside the heavy curtains. The enormous window, almost the full height of the wall, was dirty and dusty, and the corner of it was cracked. The crack was clearly not fresh; it had been carefully taped over with scotch tape to avoid injury. A thought flashed through the detective’s mind: what if…

He suddenly ripped a piece of tape off the crack, and along the uneven edge of the glass, he saw a thin crimson streak. It seemed the puzzle was starting to come together. But all the windows were equipped with locks, and the keys were kept by the watchman and the gallery director. The detective knew for sure that all the keys were in place, and there had been no report of any missing. What was going on? Another dead end.

It seemed that everyday methods wouldn’t be enough to solve this case. We suggest turning to technological methods and seeing how progress, science, and new technologies might help in the search for the missing painting.

Modern technologies have developed to such an extent that sometimes it seems like crimes are only committed by desperate thrill-seekers looking for a new adrenaline rush. And finding a missing painting in today’s world is an easy task.

Especially since everything is written on the face.

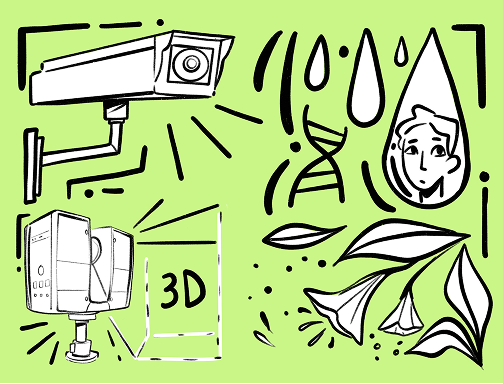

We live in a world where every step is known. In large cities, it’s unlikely there’s a single alley left without surveillance cameras. Modern investigators turn to video surveillance systems first to identify suspects. This helps them track who entered and exited a location and allows them to use facial recognition methods. While still not perfect and under continuous development by scientists, it is now possible to identify a person by comparing their real-time image with a photo from a database.

Experts are confident that soon software will be available that can convert 2D images into simulated 3D models of a person’s face in about a second. The resulting image can then be analyzed using all the facial recognition algorithms.

However, there are times when cameras don’t capture anything extraordinary, and the recording might cut off at the most crucial moment. This is exactly what happened in our case — the surveillance cameras near the gallery didn’t show anything unusual, and the recording suddenly stopped at 4:00 PM. “Technical issues,” explained the director. Indeed, the technical service confirmed his complaint about the cameras’ performance that day.

The detective had already decided that all was lost when he suddenly noticed a camera at a shop on the neighboring street. It had a view of the gallery from the side where the cracked window had been found.

The shop’s camera recorded that exactly at 3:00 AM, the window opened from the inside: it became clear that this was the window through which the painting was taken. The thief’s face was not visible, but the camera clearly captured the image — the thief gracefully, like a cat, crawled through the window, which then suddenly slammed shut behind him. On the other side of the window, there was clearly someone — it was impossible to make out details, but it was clear that the thief had an accomplice. And this person was clearly someone familiar with the gallery.

The detective began thoroughly examining the video footage, while in the lab, experts were analyzing the brown stain he had found.

It’s All About the Blood

DNA phenotyping is a young but very promising forensic method that helps reconstruct the appearance of a criminal based on their genes. The procedure determines the color of the criminal’s hair and eyes, as well as their race, with 86% accuracy.

Even if the DNA of a suspect doesn’t match any sample in the police database, forensic experts can still identify distant and close relatives who have voluntarily undergone genetic analysis in search of relatives.

So what happened in our case? Experts in the lab, to which the detective sent the materials, managed to establish that the brown stain was not tomato juice, but a drop of blood. It likely belonged to a man of European descent with light hair and gray eyes, and a matching profile was found in the criminal database.

Mr. Ogilvie was from these parts, but had not lived in the town for a long time. He had been convicted several times for theft of luxury goods and art. Neighbors who knew his family confirmed that he had recently returned to town to visit his old friend — the gallery director. It seemed that the puzzle was coming together: in the video footage from the camera at the entrance, the detective found a man resembling Ogilvie who had entered the gallery that day during lunchtime.

Usually, the director arrived at the gallery early in the morning, but on this day, he appeared only closer to lunchtime, and according to him, left late at night. Mr. Dean was already on his rounds when the director left for home, so he couldn’t give the exact time. Or maybe he hadn’t left at all?

There were still many questions, but not enough evidence. The investigation continued, but after consulting with the police commissioner, the detective decided to detain Ogilvie.

Pollen — The Cure for All Troubles

Flowers are a joy for the eyes, and recently, they’ve also become a useful tool for forensic science. Palynology, the study of pollen, is a very new discipline, but it’s already helping forensic experts around the world in their search for criminals.

Pollen is everywhere where flowering plants exist, and as we know, they bloom at different times. It acts as a biomarker that helps track a criminal and determine the map of their movements.

The interrogation of Ogilvie yielded nothing — he claimed he left the gallery around six in the evening. This was impossible to disprove. As for the blood on the glass and the floor, he explained that he had been trying to help his old friend seal a crack in the window and had cut himself. Moreover, he claimed he had never even seen the missing painting.

The commissioner was ready to release the suspect, but the detective remembered something: he had seen unusual flowers at Ogilvie’s house while questioning the neighbors. They were rare in these parts and bloomed only at night, with white, fleshy buds.

Palynologist experts confirmed: pollen from Brugmansia (the name of the plant) was found on the curtains and on Ogilvie’s clothing. But what was even more interesting, it was also found on the wall where the stolen painting had once hung, as well as in the director’s office and on his personal belongings.

The director was detained, and he turned out to be more cooperative than his friend.

Three-Dimensional Technologies

The case was almost solved: all that was missing was a complete picture of the crime. But even that was provided to the detective with the help of modern technology.

Nowadays, forensic experts can use 3D scanners to create an accurate model of a crime scene. This allows them to detail and visualize the surrounding environment, which can aid in analyzing the events. Moreover, this method helps forensic specialists visualize the sequence of events and understand what happened. It can also be useful in legal proceedings.

After recreating the 3D model with the help of experts and considering all possible scenarios, the detective clearly outlined the events of that night in his mind.

At noon, Ogilvie entered the gallery, introduced himself at the security desk, and immediately headed to the director’s office. Preparations began. The director had long complained that the city budget was not providing sufficient funds and was very upset with the city governor. Apparently, that’s why he decided to steal the painting and receive a large sum from the insurance company for it.

And for help, he called upon an old school friend who was knowledgeable about crimes and skilled at covering his tracks. But things didn’t go as planned.

The director, after tampering with the surveillance system, disabled the cameras and, turning to the technical staff, secured a reliable alibi for himself. All preparations were complete, and all that was left was to lie low and wait.

At midnight, when Mr. Dean was making his rounds, the director’s office door was locked. He often locked the door, so Mr. Dean didn’t think anything of it. When everything in the gallery went silent, the accomplices set to work.

The window through which the painting was planned to be taken was old, with a swollen wooden frame, so it opened with difficulty. And when it finally did open, a treacherous crack appeared in the very corner, which Ogilvie accidentally cut his finger on while climbing over the high windowsill.

The director noticed this and tried to hide the crack with painter’s tape. That night, he didn’t leave the gallery and early in the morning called the commissioner to report the stolen painting. He immediately understood that the commissioner wouldn’t want to deal with the case and decided to blame Mr. Dean, saying he was old and wouldn’t get much punishment anyway. But then the detective intervened!

Thus, through this story, we saw how modern technology helps unravel even the most complicated cases and exonerate the innocent.

Scientists have decoded the human genome. We’ve decoded the genome of interest. Only pure science and facts.

Thank you!