The laws of math vs. the laws of life: a christmas tale with a happy ending

By all the laws of good media, the very last issue of the year should feature a Christmas tale. The Global Technology magazine is good media, so it is with all trepidation that it joins the exciting tradition.

A Christmas tale should always include an Elf, Santa Claus, Santa’s reindeer and the desperate belief that there will be a million billion chances ahead and the new year will be a little better than the previous one.

Our Christmas tale has it all. And even more.

Today I’ve bought a scarf for myself. In a very ordinary store. You’ll say, “What so special, buying a rag around your neck.” It’s a big deal for me because I’ve never worn a scarf before.

Since I was nineteen years old, my neck has always been adorned with a small leather string on which hung a tiny leather bag, the size of a thimble. And never once have I taken it off my neck. I swam with it in all the oceans, fell under the anger and mercy of nature, even was in shootings, but no harm has ever been done to that very simple leather string on my neck.

You won’t believe it, of course, and for nothing. I’m not at the age to lie. Then you’ll probably ask, “What happened to your string?” Nothing. It didn’t break, it didn’t fall off, it didn’t wear out with time, it just disappeared. Just like that, I wake up on Christmas morning and it’s gone.

First I stayed up too late to solve the Riemann hypothesis, and then I had a dream that reminded me of an incident that happened to me in my distant youth. Maybe it can shed some light on the mysterious disappearance of my talisman.

I will, of course, tell you this story and at the same time tell you how I managed to find myself in the image of the Little Prince, and why sometimes it’s better to leave math in a notebook.

‘And how long are you going to sit here? It’s cold,’ said the Christmas Elf, shivering because of the frost.

It was an unusually harsh winter this year, and it seemed that all the celestial forces, or whoever it is who controls the weather, had finally decided to come together to take revenge on the world for all those technological and ecological experiments. Not even Christmas biting at the heels could save people from the agonizing desire to get to a warm place, get away from it all, and just get through this winter.

Cars were drowning in endless traffic jams, the wind mercilessly tore garlands off roofs and facades of buildings, the snowstorm shamelessly threw transparent ashes on the windows of houses. The Christmas spirit…. It doesn’t even smell like it here!

And on top of everything, this poor guy decided to end all problems at once, and Elf, of course, was entrusted to save him. So with the words: “Otherwise there will be no Christmas”, they sent him to rescue the holiday.

Not wanting to follow Santa’s vain orders, Elf wandered the streets, peered into the windows of houses, twisted on the glass door of a shopping center and went to the only place that always calmed him down – to a high snow-covered cliff.

There he found this straggler who, in the image of the Little Prince, wearing only a shirt and a scarf stylishly wrapped around his neck, sat shivering in a snowdrift.

‘You don’t understand…’ rattled the Little Prince’s frozen teeth. ‘You don’t understand.’

‘If only someone could understand me,’ thought the Elf and looked around. He didn’t like it at all that this little bugger had snuck into his secret place, and now, instead of Christmas preparations, he had to find words for a man he was seeing for the first time in his life.

‘You don’t understand…’ repeated the young man again and pulled off his scarf.

‘I’ve already heard that,’ the Elf muttered harshly, watching as the merciless whirlwind picked up the plaid scarf and, with all the might of a hungry beast, began to grind it with its icy mouth.

The elf blew on his palms and looked at the young man who he had already christened the Little Prince. He was surprised that the presence of this absurd human creature in his secret place quickly ceased to irritate him, as if the crooked cliff, covered with white snow, was now much more necessary to this klutz.

‘Have lost anyone?’

Absorbed in his thoughts, the Elf shuddered in surprise:

‘I?’

‘Well, yes,’ the Little Prince shrugged in surprise. ‘Have you ever lost anyone?’

‘No,’ the Elf barely audibly muttered.

‘Lucky you,’ the prince concluded and fell silent again.

The elf jumped in place and patted his shoulders, trying to warm himself.

‘That’s unlikely, because to lose someone you have to find someone first.’

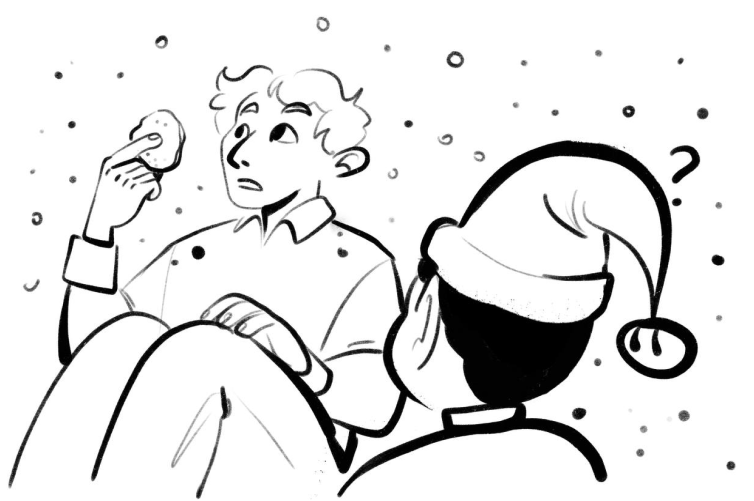

The young man scrutinized the Elf carefully:

‘Performing the actions in the correct order matters. From left to right, multiplication and division are performed first, followed by addition and subtraction.’

The Elf looked at the young man in amazement. It was the second time in a few minutes of their strange acquaintance that this stretch put the Elf in a deadlock with his phrases, and he, unable to think of anything better, continued to jump in place and slap himself on the shoulders.

‘But in all this diamond life logic with the right order of actions there is one problem.’

‘What’s that?’ the Elf asked for some reason.

‘Which action to consider first,’ the young man answered calmly and fell silent again.

The elf started bouncing around even more, out of complete incomprehension of the situation. Again this blissful man, who was apparently not cold at all in his thin, windblown shirt, was forcing him to think up some new variants of the conversation. Christmas….

‘I don’t quite get it,’ the Elf began to lose patience, ‘Are we talking about life or math now?’

‘Isn’t it the same thing?’ the young man asked calmly.

‘Well….’ the Elf hesitated.

‘Exactly, it is not the same thing,’ the prince shook his head understandingly. ‘I just had the honor to make sure of it. And I wish I had never realized it.’

The elf slammed his eyes shut in bewilderment and shook his head quickly to shake the snowflakes off his face.

‘Mathematics gives too simple explanations, and always bumps up against the formidable, indestructible rock called “life”. And if for physicists gravity is a merciless b*tch,’ the prince paused and looked down, ‘then for mathematicians…’

The elf finally lost the essence of the conversation. He didn’t understand what he should do next – to comfort the young man and say that everything will be fine and, God forgive him, to convince him that life doesn’t end with math. Remind the brash prince that it was Christmas Eve, and it would be a good idea to go downstairs to portray a sense of festivity. Or, finally, to explain to himself why he was still wasting his time on this boredom-ridden psychopath.

But the more he went over the options in his head, the more he wanted to unravel the thoughts of this human being.

‘As for me, I don’t understand math at all,’ the elf tried to comfort the prince.

‘What is there to understand?’ the young man responded phlegmatically. ‘You sit on it, you stand on it, you look at it.’

The elf looked around confusedly, but he saw nothing but the colored confetti brought by the wind and a tangerine peel sticking out of the snow.

‘Oh dear, it’s simple,’ the prince deftly picked up the peel of the once juicy fruit and began to examine it. ‘The orb allows splitting into a finite number of sets by movement. Transfer and rotation of which can form two balls of the same radius. In other words, a tangerine can be divided into a number of unmeasurable slices so that you get two tangerines.’

‘Is Math about fruit?’ asked the Elf taking the peel from the prince’s hands.

‘This particular mathematical paradox is about choice,’ the prince answered in the same cold manner. ‘But who would think of making two tangerines out of one tangerine, and who in his right mind would want to accept the axiom of choice?’

The Elf thought for a moment. He clearly remembered Santa’s words: “It is you who will save the world today!” How reluctant he was to take on this role, which was both lofty and foolish.

‘But at some point you have to make a choice,’ the Elf tried to argue. ‘For example, when duty calls you.’

‘When you have duties, you don’t exist, you are minus one,’ the prince calmly contradicted him. ‘You don’t exist, but the duty does.’

The Elf looked doubtfully at the mad young man.

‘It’s simple, too. We know that 1 + 1 = 2 because when we have a Christmas present and are given another one, we will have two boxes tied with a ribbon. We know that 2 – 1 = 1 because when, having two identical gifts, we give one away, we have one more left over. But what does 2 – 3 mean? If Santa has prepared just one gift, he can’t give three. However, suppose he can still do so – then he will be left with minus one brightly colored bundle. What does “minus one bundle” mean?

It is not an ordinary gift, it is the absence of a gift. It is a promise, and such a promise that if you add to it the most dazzling ribbon or the world’s biggest box, you get the same expressive “nothing”. No wonder the ancients thought the concept was absurd.’

‘Frankly, I think so too,’ the Elf tried to reason. ‘How can you give away what you don’t have? And how can it be counted?’

‘It’s simple too,” the young man, ignoring the unbearable cold, revived. ‘Debt minus zero is debt. Property minus zero is property. Zero minus zero is zero. Debt subtracted from zero is property. Property subtracted from zero is debt. And so on…And, notice that it doesn’t matter at all the size of the debt, its expression, the expression of the debtor’s eyes. Only something negative matters, or only something negative matters. Is there a logic to this?’

The Elf wondered. Everything the young man was talking about seemed very familiar to him. Maybe this kid wasn’t so crazy after all.

‘Tomorrow it’s Christmas and you and Santa are going to give presents to those who don’t sit on cold cliffs at night or dream of becoming a cliff themselves,’ the Little Prince shook off the snow. ‘Your present will be accepted and thanked for in the morning – that’s good, that’s a plus. But there will be those who won’t even want to open your gift – that’s bad, that’s a minus. What does the queen of sciences tell us about this?‘

‘A negative times a negative equals a positive,’ the Elf said the memorized phrase.

‘Bingo!’ shouted the young man. ‘But what will you remember from this, if you assume that every human reaction will be known to you? Only the negatives or only the positives? What will matter to you, eh? “Not my thing.” How do you make a plus out of that? And what would math say to that now?’

The Elf shrugged his shoulders in annoyance. He imagined all the stubborn hurtful labels he’d been given in his life as sticks of kindling, then he imagined assembling a big tower out of them. Then he imagined how all these cruel negatives would add up to positives, and he felt in his frozen gut that the stubborn negative twigs would never, ever add up to even one small positive. Who had invented this nonsense of negatives and positives in the first place?’

‘But still, that’s no reason to sit here alone, freezing.’

‘I knew someone would come,’ the boy said calmly. ‘According to the theory of probability, it was bound to happen.’

‘Ah,’ the Elf said with a smile when he heard something familiar. ‘It’s the one where you flip a coin many times, then divide the total number of flips by the number of sides and get the result.’

‘Simple explanation, isn’t it?’ The prince supported the El. ‘You flip, count, record. Flip again, divide, record. You sample – everything is accurate.’

‘Well, yeah,’ the Elf replied, forgetting the bitter frost. ‘Everything’s simple and precise.’

‘Yeah,’ nodded the prince, who now looked more like a snowman. ‘But the thing is that you couldn’t have guessed that you would meet me.’

‘How does he do that,’ thought the Elf. Well, how could he suppose that out of all the valiant team of green men Santa would point to him. And how could he expect that out of all the normal, good citizens of the town he would run into this lunatic. And what was there to say, the probability that on Christmas Eve someone would be sitting on a cliff and bemoaning the loss of a science was obviously zero.

The Elf felt cold again and jumped on the spot.

‘But mathematics is a science, and I always thought that probability theory is too, since it is based on reliable data,’ the Elf muttered, not believing his own words.

The little prince finally stood up and shook off the snow.

‘It had been a science,’ he said, making a snowball, ‘Until life intervened.’

The Elf carefully began to help the prince shake the snow off his back.

‘The mathematicians did the trick with the coin for a long time and wrote down the result, which made beautiful statistics, until one day they noticed that the result looked more like a lie.’

‘Is the coin lying?’ suggested the Elf.

‘Not the coin. The hands of the tosser lie, the counter airflow lies, the force with which the coin should be tossed lies, the palm on which it falls lies, even the mood of the participants during all these experiments lies.’

‘Wait,’ the elf gathered a handful of snow in his hands, made a snowball and began to toss it too. ‘This is becoming nonsense. There is a probability, then there isn’t. Nonsense.’

The little prince threw his snowball down and walked to the edge of the cliff.

‘That’s what mathematicians said when they realized they were using too little data for the result to be accurate.’

The Elf also walked to the edge of the cliff and threw his snowball down.

‘But there must be some way out,’ he looked at the prince hopefully.

‘Oh, yes,’ said the prince with a wry grin. ‘There were even two. Some mathematicians announced that there is some dark data, which any experiment can not take into account. Others have made it the whole law of large numbers – the more data, the more accurate the result.’

‘Here it is,’ the Elf responded happily and made another snowball.

‘But math could not take into account that an Elf will be on the cliff with me today. Something interfered with the exact calculation again.’

The little prince shook his head doomedly and put his face to the wind.

‘But don’t you see, I explained everything in a simple way too, and the amazing thing is that everything that happens in life fits into this exact model. Even this snow and this wind, all the water falling from the sky. From the seas and oceans, water evaporates and rises to the sky, and there it cools and collects into droplets. When it is very cold, water droplets freeze into ice crystals, they fall to the ground in the form of snow. That is constantly deforming, continuously. And this is how a mutually unambiguous and mutually uninterrupted correspondence is formed between two objects, between snow and snowdrift. Even an ordinary mug can be made into a bagel by continuous deformation, but people… How many times have you changed and deformed yourself for someone? Did it make you feel closer to someone? Did the very mutually unambiguous form?’

The Elf finally realized what the boy was talking about. He understood why Santa had sent him to save Christmas. He realized why he needed this meeting.

The Elf dared for the first time in all this time to look into the eyes of this unusual half crazy man. He blocked the ice crystals that were burning the young man’s face with his back, causing the insidious ice flakes, driven by the wind, to bite his back. The elf shouted.

‘Is that a problem? Is that a problem? You have now lost faith in the accuracy of your science,’ the Elf asked, bending down because of the snow. ‘People have lost faith in the mood, in Christmas, in miracles, in the white-bearded old man who hands out presents, in me. People believe in commercials and Coca-Cola bringing them brown holiday bottles. Because the rational is included in the life model, but the miraculous is not. We’ve got our own math here, you know, Buddy.’

The young man turned sharply on the spot, then began to trample the snow around him with his boots. He did it again and again until all the snow on the cliff was uniformly hollow.

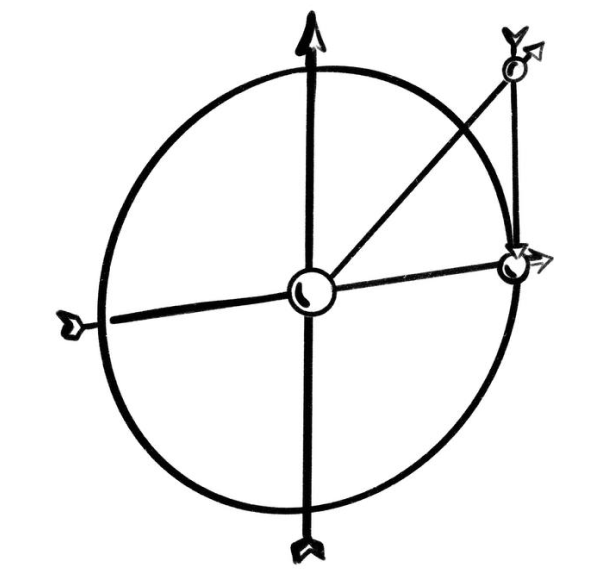

‘It’s not a problem,’ the Little Prince began to argue passionately. ‘Let’s assume that there are much more people who know that there is Santa, reindeer, Elves and Christmas, than those who deny your existence. Let’s represent them as a unit circle around point O, the source of Christmas miracles.

‘Well,’ the Elf reluctantly supported such an idea. He still couldn’t recover from the sudden rush of emotions.

‘Let’s choose the horizontal axis as the true belief, and the vertical axis will be the opposite life model, which does not include miracles. These opposite axes divide the circle into 4 parts. Did you get the picture?’

‘I have better things to do,’ the Elf thought to himself, but to avoid offending the frozen prince, he quickly nodded his head.

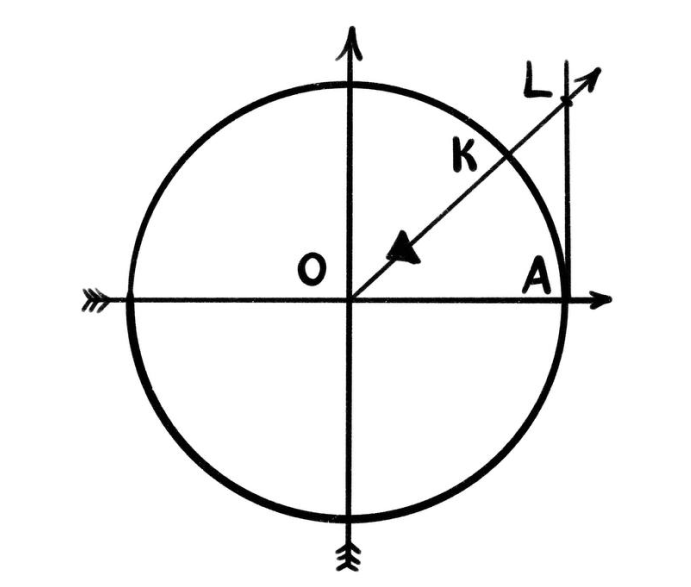

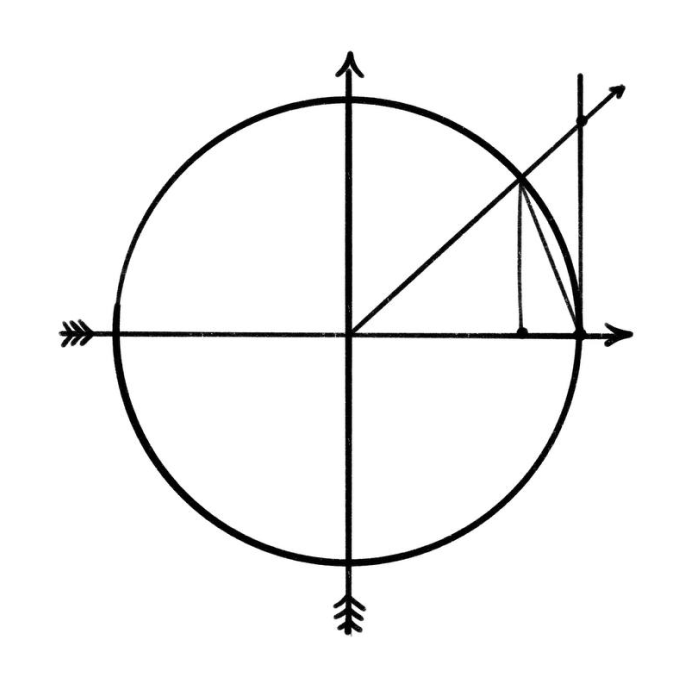

‘The enemies of the spirit of Christmas are centered on the straight AL, pointing vertically, that is contrary to true faith and true knowledge. The circle that represents the holiday itself and the straight line of the enemies of Christmas touch at point A. This is where the impact of vector OA is directed, which must break straight AL to break the spirit of those who continue to believe in the miracle. Right?’

The elf nodded desperately again, and the little prince began to draw a circle in the air and pierce it with invisible lines.

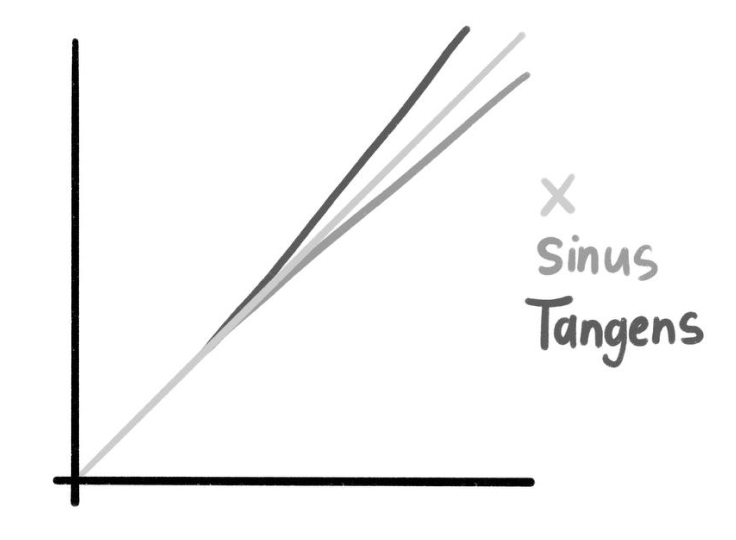

‘To ease the pressure on point A, enemies of Christmas create distracting places like The Coca-Cola Company or point L. Attracted by Point L, the misguided average person, whether a skoof, liberal, or hipster, chooses to follow the straight line OL and ends up at Point K (if he or she has ever received gifts from Santa and remains on the unit circle of believers). Thus, the person who has lost his way, in expectation of a holiday, moves away from the goal A by the length of arc AK, which is also equal to the value of the angle AOK in radians. In this case, the person’s departure from the holiday vector OA is equal to the distance from the point to the straight line, i.e. the length of the perpendicular KH. Let us denote the angle of delusion of the person who does not believe in Christmas AOK by the variable x. Then his separation KH from the true path will be sin x, and the separation of his ideal L from the place of the true struggle of his compatriots will be tg x.

The elf was getting hot from all these terms and the prince’s confused explanations, but the young man was unstoppable.

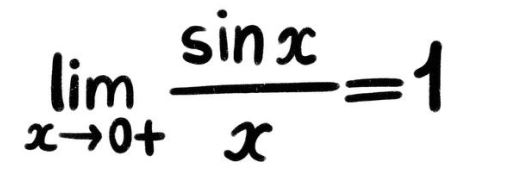

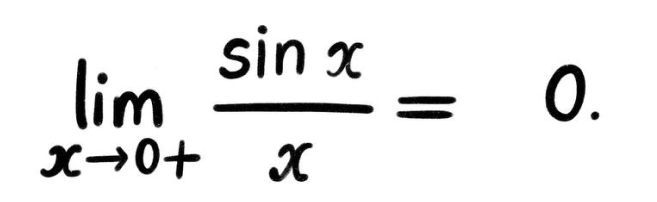

‘Now let’s answer the question: how easily can a man who believes in the Christmas miracle be turned away from the true path by misleading him?’ The little prince thought for a moment. ‘It can be reformulated as a question about the existence and magnitude of a limit. Indeed, this limit will show how much the value of sin x will change from x if x is made slightly greater than zero from zero. Exactly!’

The enthusiastic prince ran around the Elf.

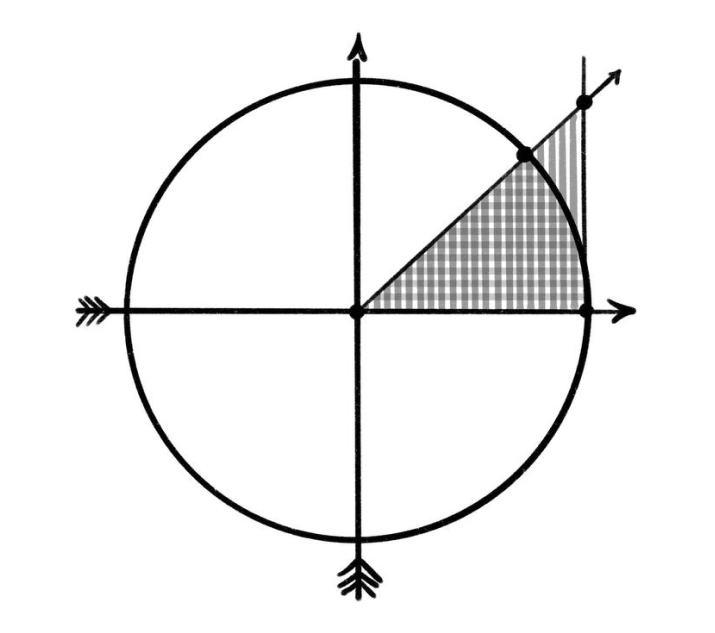

‘Let’s consider the triangle OAL of tension of relations between adherents of Christmas and its enemies, generated by the distracting point L. In it lies the sector of the OKA miracle involved in this relationship. In the sector, in turn, lies the triangle OKA, corresponding to the tension between the one who does not believe in Christmas and the true belief OA. That is, such a relationship between the squares follows:

SΔOKA < SsectOKA < SΔOAL

Applying geometric tricks, we calculate these areas:

SΔOKA = 1/2·|OA|·|KH|= 1/2·1·sinx = sinx/2

SsectOKA = 1/2R²x = x/2

SΔOAL = 1/2·|OA|·|LA| = tgx/2

And we rewrite our ratio in a concise form that can be understood not only by an Elf concerned about the fate of the spirit of Christmas, but also by a simple mathematician:

sinx/2 < x/2 < tgx/2

The little prince jumped with joy so that a drop of sweat rolled down his face, which was immediately licked away by the cold wind.

‘Do you get what we’ve just realized? Can you understand?’ He turned to the Elf. ‘To mislead a man who believes in Christmas, the enemies of Christmas have to make an effort greater than that belief!’

‘It must be great,’ said the confused Elf in a slurred voice.

‘Of course it’s great,’ the young man agreed with him. ‘It’s confirmed by rigorous and exact science. We can see that the fractional ratio of delusion and effort is less than one, which we were already happy about earlier. And we also know that cos 0 = 1, so under the convoy of simple trigonometry our sin x / x ratio successfully tends to 1 when x is reduced to zero.

That is, near the true path of the person who believes in Christmas, the deviation of the unbeliever is about equal to his delusion, and later on his increment wanes. After all, the spirit of Christmas and belief in the miracle keep people on the unit circle and do not let them slip into endless straight lines of depravity. By the way, in math, this equality is called the first special limit. However…

‘What?’ The Elf became animated.

The little prince once again drew a circle in the air and became visibly gloomy.

‘However, if we want to make sure that no delusion can lead a person who believes in a Christmas miracle off his path, then we will need a new geometry in which:

He sat down on the edge of the cliff, followed by the Elf.

‘I’ve always seen the world this way,’ the prince began to lament as the Elf sat down beside him, ‘Through such simple explanations.’

‘Simple explanations,’ thought the Elf. ‘ As for me, I haven’t understood anything at all right now.’

‘How does it feel to be an elf?’ The prince asked his subdued companion.

The Elf flinched. He could not get used to the young man’s sudden questions.

‘I’ve never thought about it,’ the Elf furrowed his brow. ‘I think we were created to make the system work. We make toys, look after the reindeer, conduct reconnaissance to find out who behaved well, who didn’t, provide stability, keep Santa safe. We elves are the backbone of everything! And when Christmas comes, all the credit goes to Santa and, oddly enough, to his reindeer. Everyone knows their names, but they just call us “Elf” and sometimes they give us a number. An elf with a number, that’s pathetic.’

‘So you’re a sine’.

‘What’s a sine?’

The elf got worried. The boy had obviously been sitting on that cliff undressed for a long time. The wind and the blizzard must have done its job, so he’s talking nonsense.

‘You do everything that the sine does,’ the prince interrupted the Elf’s anxious thoughts. ‘When we are just beginning to learn the elegance of mathematical objects, we are drawn to complex curves – epitrochoid, conchoid of Nicomedes, hypotrochoid, Cassini’s ovals and …..’

The prince gathered a handful of snow into his palm again and began molding a flower out of it.

‘And to the roses?’ guessed the Elf.

‘And to roses,’ the Prince sighed sorrowfully.

The Elf’s mind instantly flashed through the lines: “The Little Prince had a rose on his planet, a capricious and a bit flighty rose that he loved. He got tired of her and left her for a while, and it was only on Earth that he realized there were thousands of other roses, but he needed the one on his planet.”

‘So the equations of all these curves that I’ve described are expressed through trigonometric functions. And at their heart is always the sine – imperceptible but indispensable. When Pythagoras first announced his theorem, we learned the concept of “the cosine of an angle”, and the sine appeared later, as something trifling, superfluous. I have always been offended by sine, too, because it is the main one, the cosine is only its complement. The sine is stability. The sine doesn’t betray, it can’t unpleasantly surprise. There is no shame in the sine. It will not complain about life, but everyone can complain about life to the sine. Every person is close to the sine: without -1 there is no 1, without a tree there is no Christmas.’

‘Without choice there is no loyalty, without overcoming difficulties there is no happiness,’ the Elf supported the young man.

The prince nodded gratefully.

‘Understanding the sine comes with wisdom and experience, as does understanding the full importance of the processes the stealthy “elves” do. At least that’s what math says.’

At the word “math,” the young man picked up the rose he had so diligently sculpted a few minutes ago and launched it into the sky.

‘Does science lie again?’ The Elf asked cautiously.

The Prince assumed the pose of a character from a famous Christmas advertisement:

‘Observe the principle of fractions and proportions, if you praise someone and drink, then fun, hangover, and envy you will easily bear! Increase the state, apply multiplication, and every wish will come to fulfillment! Have a small sine and a large belly? Turn π/2 and it will grow! Growth is not always linear, it can slow down, then at the very start you will have to try harder! Make a golden cross-section of your friends in the picture, so they can praise you in your epitaph!’

The elf clapped his hands numbed from frost, but feeling a new rush of cold, he jumped on the spot again.

‘So you are also a poet,’ he said respectfully to the young man.

‘I am a fool!’ said the prince in despair. ‘I did believe! I did believe in these laws! I believed that when things don’t add up, you have to subtract. And you know what I did? I subtracted. I believed in the laws of symmetry, so I always did the fair thing. I live differently, I pray, I help the homeless, I donate money to hospitals and orphanages. I’ve managed to learn to love this weird sun, and also this rain, this snow that’s crumbling now.’

‘So?’ the Elf asked gently.

‘And they extinguish candles with me, invite me to the party by e-mail and pray that I don’t come. All these precise laws don’t work. They never will.’

The little prince was silent. The elf looked up at the starry Christmas sky. Somewhere out there in Santa’s workshop, the final preparations for the holiday are underway. A golden reindeer harness is being put on, a red weighty sack of presents is waiting to go, people everywhere are lighting Christmas lights. Someone is pulling out a flavorful stollen from the oven, someone is looking at a ruddy turkey with appetite, someone is cutting a juicy chicken in half, someone is proudly taking out a cholodets from the refrigerator.’

And only these two, the little Elf and the little prince, are standing on the edge of the cliff watching the glittering snow glare on the starry sky.

‘You know,’ the Elf interrupted the silence, ‘What if the queen of sciences is not wrong, just those who hurt you don’t know math at all?’

The young man looked hopefully at the Elf and at that moment the little green man saw a smile on his face for the first time.

‘According to the legend,’ continued the Elf, ‘A small pouch is hung on each elf’s neck at birth, and, according to the same legend, a piece of pure gold always lies in this pouch. In fact, there is no gold in that pouch. Here, look.’

The elf carefully removed from his neck a small leather rope on which hung a tiny piece of brown material.

‘A gift lies in this pouch and each elf can give this gift to someone only once. And I’m giving it to you.’

The elf walked up to the young man and put the most precious thing into his hands.

The young man embarrassedly accepted the gift and began to unwrap it.

‘I give you life,’ said the Elf and said goodbye.

The little prince looked once more at the Christmas sky. It seemed to him that there, in the dark infinity, a new star, different from the other stars, had been lit for him. It winked brightly at him with a silver light, and when the light from it dissipated, a sign appeared in the sky: “Watch out, Fool, don’t hurry to count!”

The Einstein-Rosen bridge? We’re building it out of facts.

Thank you!